Previous | Table of Contents | Next

1.

The Chaco Additions Survey

Ruth M. Van Dyke and Robert P. Powers

¶ 1 The Chaco Additions survey was conceived on December 19, 1980, when President Carter signed into law a bill which converted Chaco Canyon National Monument into Chaco Culture National Historic Park. The newly created park was established in response to profound changes in Chaco's physical and intellectual environments. The American energy crisis of the 1970s precipitated a tremendous surge in uranium, coal, petroleum, and CO2 exploration and extraction throughout the San Juan Basin of northwest New Mexico. Chaco Canyon, located in the center of the San Juan Basin, was at the geographic core of the energy boom. Although exploration for, and recovery of, geologic resources was prohibited within the monument, by the 1970s, coal and uranium drill rigs, oil pumpjacks, and seismic line corridors were advancing to the very boundaries of the park. The once splendid silence and isolation of Chaco was fast becoming a memory.

¶ 2 At the same time, longstanding anthropological conceptions about Chaco were undergoing their own transformation. For a hundred years, Chaco Canyon had been recognized as the home of an enigmatic people who constructed massive sandstone pueblos, or great houses, and large subterranean ceremonial chambers known as great kivas (Morrison 1876; Hewett 1936; Judd 1927, 1959, 1964; Pepper 1920). Extensive excavations had uncovered turquoise, shell and jet ornaments, copper bells, macaw feathers, and exotic ceramic vessel forms, but few skeletal remains (Judd 1954; Pepper 1909). Elaborate architecture and rich artifactual remains were present, but there was a paucity of people to produce them. A further complication was the fact that although the ancient Puebloans were farmers, Chaco Canyon is in the midst of an area that is, at best, marginal for agriculture. As A. V. Kidder pointed out, Chaco

...is little better than a desert; many parts of it, indeed, are absolutely barren wastes of sand and rock which do not even support the usual dry-country flora of the Southwest. It is almost devoid of springs, has no permanent streams, is subject to severe sandstorms, is blistering hot in summer and bitterly cold in winter. It is hard to see how life in Chaco could have been anything but a continual struggle for bare survival (1924:179).

¶ 3 Sites with Chacoan architecture have long been known from throughout the San Juan Basin, and early researchers such as Roberts (1932), Martin (1936), Morris (1939), and Gladwin (1945) speculated about links between these outliers and Chaco Canyon. However, Chacoan studies tended to be canyon-centric until the early 1970s, when the discipline began to encourage regional approaches. In 1971, a long-term research program known as the Chaco Project was initiated as a joint effort of the National Park Service and the University of New Mexico. During this project, a new conception of Chaco gradually emerged, in part as the result of the in-depth examination of linear features putatively termed roads. Stairways pecked into sandstone cliffs, long rubble alignments, and barely visible linear depressions on the mesa tops had long been noted by old Chaco hands (Vivian 1997). These features had been generally dismissed as ceremonial racetracks or processional paths used in religious ceremonies (Judd 1954:346-347, 1964:141-142).

¶ 4 In the early 1970s, the discovery of subtle vegetation and soil patterns visible only on aerial photography demonstrated that these linear depressions extended for substantial distances outside Chaco (Ebert and Lyons 1977; Hitchcock 1973; Lyons and Hitchcock 1977). The realization that these largely ignored features were roadways finally gave substance to decades old anecdotes like Harold Gladwin’s 1928 note on a survey form for the Skunk Springs site that “the Navajo say that a clay road was once built from this ruin to Pueblo Bonito, a distance of 35 miles (56 km), over which the pine logs were carried from the Chuskas to build the great pueblo at Bonito. Sections of the road are said to be still in use by the Navajo” (Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Archive, Collection 0002/043.001-70).

¶ 5 Within ten years, a combination of remote sensing techniques and ground verification defined a prehistoric road system which extended outward from Chaco Canyon into the surrounding San Juan Basin (Kincaid 1983; Nials et al. 1987; Windes 1987: 95-139). The Great North Road and the South Road radiate for a considerable distance from Chaco Canyon; these and a number of other segments link Chaco Canyon with outlying Chacoan settlements. These sites, known as outliers, consist of a Chacoan structure or great house, and often a surrounding community of small house or habitation sites and a great kiva (Marshall et al. 1979; Powers 1983; Kantner and Mahoney 2000). Today, “road fever” has abated somewhat with the realization that some roads are but short segments visible only in the immediate area of great houses (Roney 1992). Nevertheless, the excitement surrounding initial recognition and documentation of the roads spurred the realization that outlier great houses were contemporaneous with Chaco Canyon great houses, and that Chaco Canyon cannot be explained in isolation.

¶ 6 By the early 1980s, Chaco Canyon appeared to be the ancient cultural and geographic center of a large desert realm referred to as the Chaco Phenomenon (Irwin-Williams 1972) or the Chacoan system (Judge 1979; Marshall et al. 1979; Powers et al. 1983; Doyel et al. 1984). Over the past two decades, several systematic efforts have been undertaken to document outlier communities. Today, over 100 Chacoan outliers are known from the San Juan Basin and adjacent areas of southwest Colorado, southeast Utah, and northeast Arizona (Durand and Durand 2000; Fowler et al. 1987; Gilpin and Purcell 2000; Hurst 2000; Jalbert and Cameron 2000; Kantner and Mahoney 2000; Kendrick and Judge 2000; Marshall et al. 1979; Powers et al. 1983; Warburton and Graves 1992; Windes et al. 2000; Van Dyke 1999a). Spatial and temporal variability among outliers comprise the basis of Breternitz, Doyel, and Marshall's (Doyel et al. 1984:38-39; Marshall et al. 1982:1231) definitions of “ancestral” outliers, in which Bonito-style architectural elements were introduced into communities that had existed for several previous centuries, and “scion” outliers, which were established as Chacoan colonies during the late Pueblo II period. Although the relationships between outliers and Chaco Canyon today do not appear to be as straightforward as was first assumed (Kantner and Mahoney 2000; Van Dyke 1999b), the concept of a unified Chacoan system was the driving force behind legislation to identify, protect, and explore outlier communities. An excellent summary of recent research and approaches to understanding Chaco may be found in Mills (2002).

¶ 7 During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the escalating energy boom posed a serious threat to the newly recognized Chaco Phenomenon. At the time, it seemed as though the far-reaching system of sites might be destroyed before it could be fully studied or appreciated. To prevent such an outcome, W. James Judge, Chief of the Chaco Center, and Brian McHugh, Chief Ranger at Chaco Canyon National Monument, prepared a legislative proposal to protect representative portions of the Chacoan System by adding them to the monument.

¶ 8 The purpose of the proposal was two-fold. First, largely as a result of an inventory survey conducted by Alden C. Hayes (1981) between 1972 and 1975, it was apparent that the density of prehistoric Puebloan sites continued unabated beyond the monument boundaries. These sites, including pueblos, field houses, water control systems, camps, and outliers were no less important to understanding Chaco archaeology than the sites already protected. Also, in order to preserve the modern natural scene as the closest approximation of the prehistoric setting, land additions conforming to the canyon's natural physiographic boundaries were essential. The monument boundaries provided no protection against energy or mineral extraction in the upper portions of the tributary drainages of Chaco Wash — activities which might not only impair virgin scenery, but could potentially introduce toxic wastes and high sediment loads into the monument. Without direct control of entire watersheds, it was impossible to completely protect the environment of any part of Chaco.

¶ 9 The second, even more ambitious part of the proposal was to provide protection of a sample of the Chaco outliers, their surrounding communities, and portions of the road system. Without federal protection at a level commensurate with that afforded by national park status, it was feared the outlier communities and roads would disappear beneath a ganglia of mine sites, housing projects, fast-food emporia, and utility corridors. Although existing federal law provided for mitigation of many of the sites, dissection would have been piecemeal, and the portions of the system left untouched would have been too incomplete to allow any real comprehension of this singular prehistoric achievement.

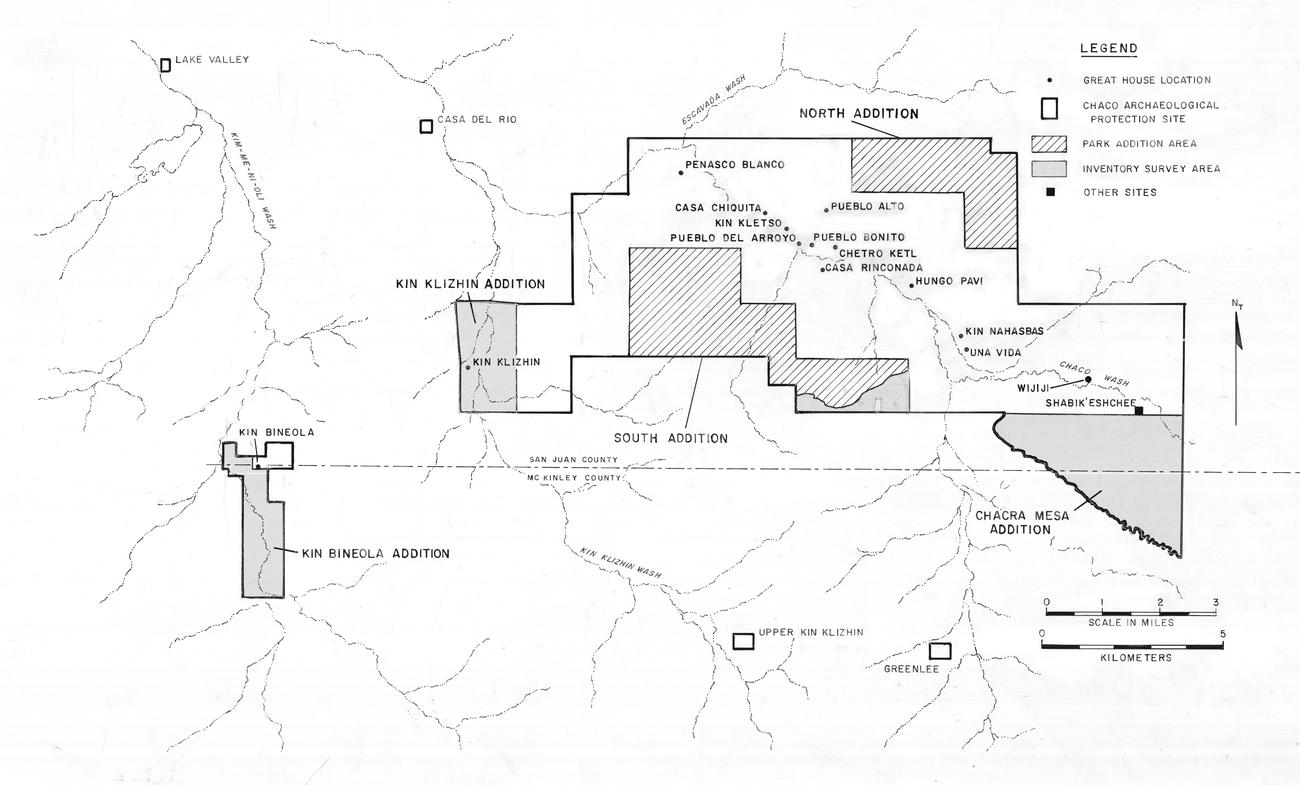

¶ 10 When the much-revised Judge-McHugh legislation was passed in 1980, it added approximately 5,263 ha (13,005 acres) to the park. The new lands, or additions, included six separate tracts: the North (1,001 ha [2,473 acres]), South (1,877 ha [4,639 acres]), Chacra Mesa (1,346 ha [3,325 acres), Kin Klizhin (502 ha [1,240 acres]), Kin Bineola (473 ha [1,168 acres]), and Kin Ya'a (65 ha [160 acres]) units. The first four are contiguous, joining the monument at its previous boundaries. Kin Bineola, located 18 km to the west, and Kin Ya'a, located 42 km to the southwest, are detached units (Figure 1.1).

|

Figure 1.1. Chaco Culture National Historical Park showing additions and inventory survey areas. The Kin Ya’a unit, not shown, and is located approximately 40 km south of the park. |

¶ 11 The legislation also established 33 Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Sites throughout the San Juan Basin; today, that list has grown to 39 sites. Each site includes a great house, and many have an associated community of surrounding, smaller sites, a great kiva, road segments, and other limited activity sites. The protection sites vary in size from 2 to 1,279 ha (5 to 3,160 acres) and total 5,816 ha (14,372 acres). Under the guidelines established by the legislation, Chaco Protection Sites are managed by various federal, tribal, and state entities on whose lands the sites are located. A few sites on private land are managed under cooperative agreements between the private owner and the Bureau of Land Management. Each agency is charged with ensuring that cultural resources within the tracts are preserved. Energy extraction and other modern activities are allowed insofar as they do not impact the archaeological remains. Unified management of the sites is provided by an interagency management group composed of representatives of each of the major federal, tribal, and state land managing agencies.

¶ 12 In addition to these enactments, the legislation also directed the Chaco Center to continue its research activities at the park and outliers. Existing statutes such as the Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (as amended in 1980) and Executive Order 11593 already directed federal agencies to locate, inventory, and evaluate archaeological sites in order to identify those eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. This enactment carried the Chaco Center’s role even further. Sites in the addition areas were to be inventoried and targeted for additional research.

The Chaco Additions Survey

¶ 13 In the fall of 1982, Robert Powers was assigned the task of directing an intensive, 100% inventory of the unserved park additions and the Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Sites. The Chaco Archaeological Protection site portion of the survey did not materialize, as the necessary interagency funding was delayed due to reduced agency budgets, the federal deficit, and other administrative problems.

¶ 14 Over 2,711 ha (6,700 acres) of the Chaco Additions area, including all of the North Addition, Kin Ya'a, and most of the South Addition, had already been examined by either the Judge sample survey (Judge 1981) or the Hayes inventory survey (Hayes 1981) prior to becoming part of the park (Figure 1.1). This report documents the inventory of the previously unserved park additions (2,545 ha [6,288 acres]) carried out over the 1983-84 field seasons. These areas include all of the Kin Klizhin, Kin Bineola, and Chacra Mesa parcels and a small portion of the South addition (Figure 1.1). A total of 957 sites and 183 isolated occurrences were documented. The inventory, in accordance with existing laws and National Park Service policy, collected information both for cultural resource management and research purposes. During both field seasons, the survey team consisted of two crews of three to four archaeologists. Peter J. McKenna and Robert Powers were the crew chiefs. The crews were composed as follows:

- Peter J. McKenna (crew chief and ceramicist)

- H. Wolcott Toll (general recorder, June 1983)

- Judith A. Miles (general recorder, July to September)

- Elizabeth O. Wills (lithic specialist)

1983

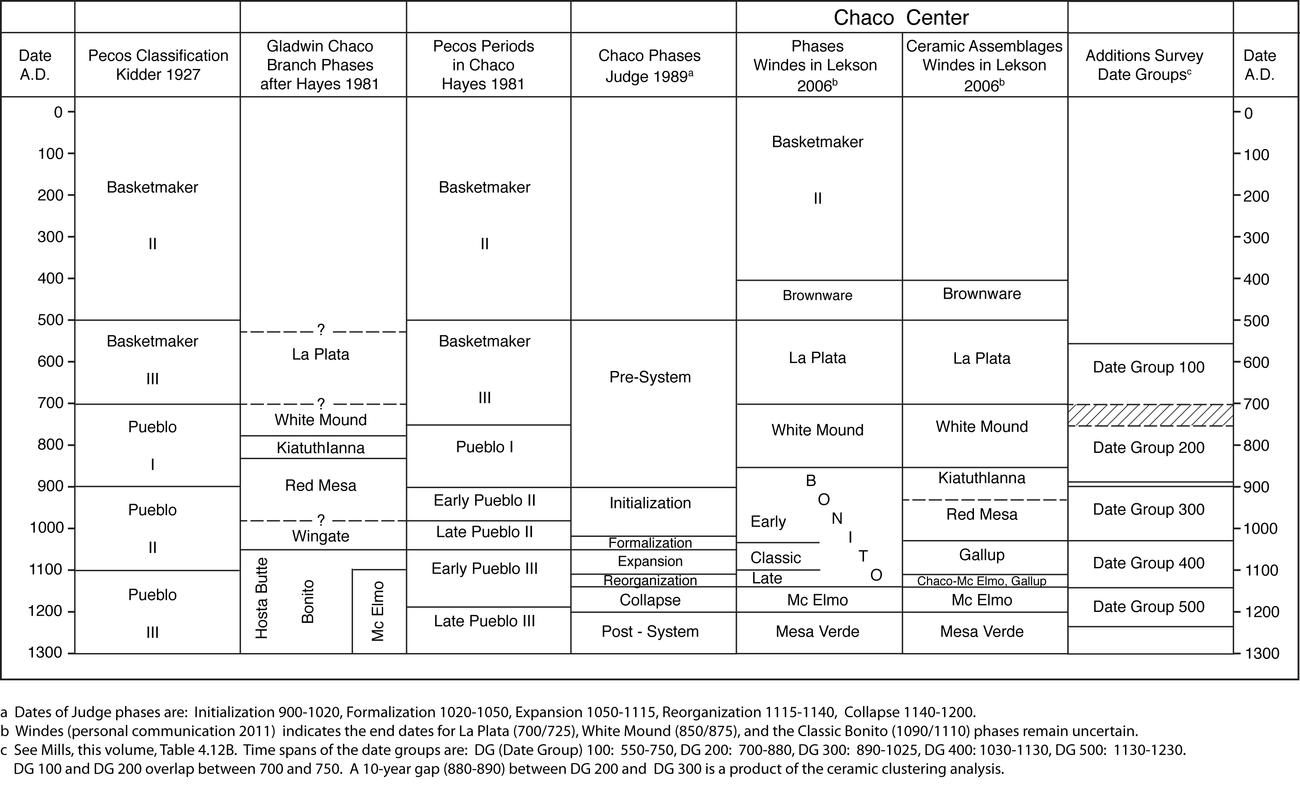

Crew 1

- Robert Powers (crew chief and general recorder)

- Daisy F. Levine (ceramicist)

- Lisa C. Young (lithic specialist)

Crew 2

¶ 15 Volunteers during the 1983 season included Barbara M. Hegarty, Scott P. Blanchard, Wirt H. Wills, John D. Speth, and Stephen H. Lekson.

- Peter J. Mc Kenna (crew chief and ceramicist)

- William Brancard (general recorder)

- Martha Graham (lithic specialist)

- Jay Holley (volunteer and general recorder)

1984

Crew 1

- Robert Powers (crew chief and general recorder)

- Barbara J. Mills (ceramicist)

- Lisa C. Young (lithic specialist)

- Mary Stiner (general recorder and mapper)

Crew 2

¶ 16 Late in the 1984 season the two crews were combined after most members left to return to school. Daisy Levine (ceramicist) and Thomas C. Windes (general recorder) filled in to form a final crew consisting of Powers, McKenna, Levine and Windes.

Previous Investigations at Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola

¶ 17 The Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola great houses have long been the focus of archaeological interest. However, little of the surrounding communities had been systematically documented prior to the current project. Kin Klizhin is located on lower Kin Klizhin Wash, an ephemeral drainage approximately 8 km southwest of Chaco Canyon. The two to three story great house contains approximately 33 rooms and is noted for its tower kiva. A review of information about Kin Klizhin appears in Marshall et al. (1979:69-72), and much of the following is drawn from that work. Kin Klizhin is derived from the Navajo Kin Łizhin, or “black house;” Kin Daałzhiní, or “black houses,” is a variant. Kin Daałzhiní is mentioned in the story of Hail Way (Reichard 1944:5), but it is not clear that this actually refers to Kin Klizhin, as Kin Daałzhiní is also an alternate name for Chetro Ketl and one other site (Fransted 1979:32-33). The earliest written descriptions of the Kin Klizhin great house appears in Morrison’s (1876) and Holsinger’s (1901) reports. Richard Wetherill apparently filed a homestead claim at Kin Klizhin, but in error–he thought the plots were at Pueblo Bonito, according to McNitt (1957:201). Over the ensuing decades, investigations at the ruin have included collection of tree-ring samples, stabilization, and examination of associated irrigation features.

¶ 18 Irrigation works associated with Kin Klizhin are described by Morrison (1876), Holsinger (1901), Hewett (1905, 1936) and Judd (1954:57). Gordon Vivian investigated irrigation features near the ruin between 1964 and 1966. Gwinn Vivian performed additional mapping, recording, and test excavation of the irrigation features in the early 1970s. Florence Hawley collected tree-ring specimens from Kin Klizhin for the School of American Research in 1932. Bannister et al. (1970:24) published three tree-ring dates from Hawley’s specimens that indicate construction took place around A.D. 1087: 1038p-1086++v, 1065p-1087c, and 1066p-1087c.

¶ 19 Kin Bineola is located on the alluvial floor of Kim-mi-ni-oli Valley approximately 18 km west of Chaco Canyon. The massive, three-story, E-shaped structure opens to the south and contains an estimated 210 rooms. Marshall et al. (1979:57-68) summarize the available information on Kin Bineola, and much of the following description is taken from that work. The Navajo name for Kin Bineola is Kin Bii’ Naayolí, “house in which the wind whirls.” Variants of this name include Kin Bił Dahnayolí — “house with fabric in the wind,” and Kin Jóleehí — “roping house” (Fransted 1979:31). Kin Bineola appears in the origin legend of Excess Way (Kluckhohn 1967:166). The first written description of the Kin Bineola great house appears in Holsinger's (1901) report. Richard Wetherill is reported to have found many burials near Kin Bineola in 1900 (Lister and Lister 1981:233), but confusion surrounds Wetherill’s purported activities in the vicinities of both Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola.

¶ 20 As at Kin Klizhin, investigations have included collection of tree-ring samples, stabilization, and examination of irrigation features. Tree-ring specimens were collected from Kin Bineola between 1923 and 1963 by Douglass’ First Beam Expedition, by Florence Hawley for the School of American Research, and by Charles Voll during National Park Service stabilization. On the basis of these specimens, Bannister (1965:168-170; Bannister, et al. 1970:20-21) reports 26 dates in two clusters, one at A.D. 942-43, the other at A.D. 1111-1120. The early dates from Rooms 35, 50, and 51 in the central wing correspond with an early masonry style. The later dates are from Rooms 9, 45, and 68. Holsinger (1901), Hewett (1905, 1936), and Judd (1954) describe dams, reservoirs, and ditches in the vicinity of Kin Bineola. Between 1964 and 1966, Gordon Vivian mapped and recorded a number of these. Gwinn Vivian revisited the area and did additional mapping and recording of the irrigation features in the early 1970s. The work of both Vivians will be summarized in a forthcoming book by Gwinn Vivian (n.d.)

¶ 21 In the 1960s, the National Park Service undertook stabilization at Kin Bineola. In 1972, as part of the monument inventory led by Alden Hayes (1981), National Park Service archaeologist David Barde reported two quarry locations on mesa tops to the northeast and northwest of the great house. Lyons et al. (1972) conducted test excavations into purported irrigation features at Kin Bineola and Lyons and Hitchcock (1977) examined the area using remote sensing and aerial reconnaissance.

Project Objectives

¶ 22 The project’s cultural resource management and research objectives originally were designed for an archaeological inventory of both the park addition and the protection site areas. As the scope of the project changed, two primary cultural resource management objectives emerged: (1) accurate identification and location of all sites; and (2) recovery of basic classificatory and descriptive data, including cultural affiliation, temporal placement, site function, description of site features, description of material culture, and environmental setting. Sites also were evaluated with respect to condition, the need for preservation and protection, and National Register eligibility. Research objectives for the project included: (1) description of the archaeological remains; (2) use of surface survey artifacts to identify differences in the function of archaeological sites; and (3) examination of the Canyon and its periphery as a single settlement system. Each of these goals are reviewed below.

Description of the Archaeological Remains

¶ 23 The primary research objective for the Chaco Additions survey was the description of the archaeological remains. Descriptive information in the following chapters is organized by three parameters: cultural affiliation, temporal affiliation, and physical description.

Cultural Affiliation

¶ 24 One or more of six categories of material cultural affiliation -- Paleoindian, Archaic, Anasazi, Navajo, Historic, and unknown -- were assigned based on the presence of diagnostic materials. Paleoindian remains were identified by diagnostic projectile points (e.g., Clovis, Folsom, Milnesand) and tool production technology. Archaic proveniences were identified by diagnostic projectile points (e.g., Jay, Bajada, Armijo), ground stone (basin metates, one-hand manos), and absence of ceramics. Anasazi manifestations were primarily identified by Anasazi ceramics and/or characteristic architectural features (pueblos, kivas, pit houses), and to a lesser extent by diagnostic projectile points (triangular, corner and side-notched points). Navajo affiliation was assigned on the basis of Navajo or historic Puebloan ceramics and/or architectural features (hogans, ash heaps, sweat baths). Late 19th and early 20th century Euro-American artifacts were also frequently present on Navajo sites. Sites without culturally diagnostic architecture or features, but with Euro-American manufactured materials (steel, glass, rubber, plastic, aluminum) were identified as historic. This generic category is descriptive rather than cultural, and presumably includes sites created by individuals of Navajo, Hispanic, or Anglo heritage. If no diagnostic materials were encountered, a provenience's cultural affiliation was designated as unknown. When cultural affiliation could not be narrowed to a single category, combination categories such as Archaic/Anasazi or Navajo/Historic were applied in the field. During the analysis, materials from these lump category sites were treated in a variety of ways by the individual analysts.

Temporal Affiliation

¶ 25 Several levels of temporal control resulted from the field work and subsequent analyses. These include: archaeological remains of unknown cultural affiliation for which it is impossible to assign any date; undated sites or features of known cultural affiliation that are classed as prehistoric or historic; and archaeological remains with estimated beginning and end occupation dates assigned on the basis of temporally diagnostic artifacts, tree-ring dates, and/or ethnohistoric data. Within this spectrum, the degree of temporal control obtained by the survey varies greatly but it often corresponds with cultural affiliation.

¶ 26 The few Paleoindian and Archaic remains are largely undated or very generally dated by a few putatively diagnostic lithic materials. The dates given are those assigned to typologically similar artifacts in adjacent regions (Irwin-Williams 1973; Judge 1973). Dating of Anasazi and Navajo sites is based on temporally diagnostic ceramics. Date ranges, or periods of production for specific ceramic types, are discussed by Mills (Chapter 4, this volume).

¶ 27 Based on the date spans of individual ceramic types represented at Anasazi proveniences, an assemblage date range was assigned after assessing the temporal overlap and relative frequency of the constellation of types present. Anasazi sites with begin and end dates spanning a period of 200 years or less were used in a cluster analysis to establish date groups. Mills presents a detailed discussion of this process in Chapter 4. The purpose of the date groups is to establish temporal units that accurately reflect the mean occupation spans of Anasazi sites from A.D. 500 through the early 1300s for those sites occupied less than 200 years and to provide controlled temporal units for comparative analysis. Sites occupied less than 200 years have been dated by two methods — begin and end dates, and date group. The occupation span for each method varies slightly, the former representing the estimated occupation span based on the site's ceramic assemblage, and the latter representing the span established by clustering the begin and end dates of all sites occupied in the same era. The survey date groups established by the analysis are shown in Figure 1.2 relative to the Pecos Classification and other time schemes established for the Chaco area.

|

Figure 1.2. Chaco area temporal classifications. |

¶ 28 At Navajo and Historic sites, known production spans for manufactured, Euro-American artifacts provided a basis for estimating beginning and ending occupation dates (Powers and Warburton, Chapter 7, this volume). In addition, wood samples yielded dendrochronological dates, and informant interviews provided further oral information about dates of occupation (W. Powers, Chapter 8, this volume).

Physical Description

¶ 29 In the following chapters description of the physical remains found on sites is organized hierarchically from general to specific. Survey area refers to one of the four survey tracts (Kin Klizhin, Kin Bineola, Chacra Mesa, and South Addition). The site is the primary descriptive unit employed by the survey. A site is defined as a spatially discrete clustering of archaeological remains potentially including several cultural groups and time intervals. For instance, Archaic and Navajo features and artifacts occurring in an overlapping area were recorded as elements of the same site.

¶ 30 More useful for analytical purposes is the component. As defined by the survey a component is the portion of a site assigned to the same culture and site type. As such, a component may include features from one or more time intervals and embrace a variety of features used for different purposes. As an example, many sites recorded by the survey were occupied either continuously or intermittently (often indistinguishably) over long intervals, resulting in components dated to multiple date groups. Each component was given a designation or site type name, usually derived from the most significant structural feature present, or in the absence of a structural feature, the dominant nonstructural feature. The site type classification system used by the survey is derived from 16 site categories established by Hayes (1981:16-17) for the 1972 inventory of the monument, but adds another 16 types either subsumed in, or not included in his classification (Table 1.1). As readers delve into the following chapters, it will be helpful to remember that components are broadly defined1The components established and used in the Anasazi settlement, typology and demography analysis (Chapter 2) provide an exception to this general statement. In this chapter somewhat different criteria were used during the analysis to redefine the components established in the field. In her typology analysis, Sebastian used function, space and time to create a larger number of more discrete components. For example, at site 29SJ 342, Component 1 has a site type designation of habitation and includes five features: a roomblock, pithouse, hearth, trash mound and a possible kiva. Component 2, site type field house, includes two features, a field house and a sherd and lithic scatter. Component 3, site type scatter-with-slabs, has one feature, a slab scatter. All three components were placed in the A.D. 890-1025 date group, but because the components are spatially separate within the site, and are likely to have had different functions, they were distinguished. In contrast, for the ceramic (Chapter 4) and the lithic analyses (Chapter 5), only Components 1 and 2 were recognized (the components established in the the field), with the slab scatter included as a sixth feature of Component 1. Since most ceramic and lithic analyses were conducted at the feature level, component separation was of less concern. The details of component definition will be of little interest to many readers, but because the Chapter 2 components differ in number and composition, it is important to be aware that they are not precisely comparable to the components of Chapters 4 and 5. and that the site type, is in effect, simply a classificatory label for each component.

Table 1.1. Site Type Definitions.

¶ 31 Inferior to the component in inclusiveness, is the provenience or feature, which refers to a structural feature or group of artifacts, such as a sherd and lithic scatter. One or more proveniences or features combine to form a component -- the sum of spatially related features of the same culture at a site. The feature is the smallest level of provenience used by the survey. A feature generally consists of a single archaeological manifestation such as a hearth, a lithic scatter, or a roomblock. The feature was the basic descriptive unit for recording purposes in the field, and the level at which artifact sampling and much subsequent analysis was performed. Table 1.2 lists all feature types recognized by the survey and defines those which do not double as site types.

Table 1.2. Feature Type Definitions.

¶ 32 The field provenience classification system was consolidated once the analysis was begun to facilitate comparison of physical attributes and artifacts between components and features. For the Anasazi ceramic and lithic analyses, individual site and feature types were lumped into site type groups and feature type groups in order to provide adequate sample populations for statistical comparison, and to reduce the number of types to a manageable size. To accomplish this, site and feature types were sorted into structural and nonstructural categories, then into actual groups of morphologically related types. Field houses, ledge rooms, and field house/habitation site types, for example, were lumped to form the group small structure. Similarly, field houses, ledge rooms, field house/water control features, unknown structures, and ramadas/lean-tos were combined to form the feature group small structure. A total of 26 site types were merged into 9 groups, and 43 feature types were reduced to 13 feature groups. The reduced site type and feature groups are shown in Tables 4.5 and 4.6 for the ceramic chapter, and Tables 5.6 and 5.7 for the lithics chapter. Most ceramic and lithic analysis was performed at the level of the feature group rather than the site type group, because feature groups represent similar activities that are functionally related, while site type groups can contain features that, although spatially and temporally related, may represent very different activities.

Site Types

¶ 33 For the most part the site type definitions provided in Table 1.1 do not require further note. Nonetheless, in a few instances it may be useful to elaborate upon the site type terminology used by the survey, since a number of terms may be unfamiliar or confusing. The term Chacoan structure was employed by the Additions survey to refer to any building exhibiting some or all of the following architectural features: core-and-veneer masonry, large rooms with high ceilings, multiple stories, large scale planning, direct association with a prehistoric road or great kiva, and large size and mound height relative to surrounding sites (Powers 1983:15-16). Chacoan structures include the large, architecturally elaborate buildings more familiarly known to many readers as great houses or towns (Morris 1939; Vivian 1970a, 1970b), but also encompassed by the term are more modest sized structures which share the architectural attributes of great houses, but diverge from them significantly in size. With the exception of Kin Bineola, it is hard to describe any of the four structures with classic Chacoan architectural features documented by the survey as “great.” The other sites (Kin Klizhin, 29Mc 291 and 29SJ 2384) are of modest greatness in scale and size, and even if they were used as habitations, they could not have lodged more than a few dozen people. Accordingly, we have chosen to retain the field survey’s term, Chacoan structure, but great house is also used in some chapters. The two terms should be considered synonymous except where otherwise noted.

¶ 34 In contrast to the Chacoan structures, small residential pueblos with three or more surface rooms and/or one or more pithouses were much more numerous and were termed habitations. Virtually all of these dwellings, which appear to share many of the architectural attributes of small residential sites in Chaco Canyon, could also be called villages (Vivian 1970a, 1970b), or in current parlance, small sites or small houses (Kantner and Mahoney 2000; Lekson, Windes and McKenna 2006).

¶ 35 As noted above, during the analysis of the survey data we combined individual site types into larger, more analytically useful site type groups, and as a result of this habitations were re-branded as large structures. Similarly, structures with one or two rooms, identified by the survey as field houses or ledge rooms were combined into a site type group termed small structures. In hindsight, use of these terms was not an inspired choice, but they are so in-grained in the fabric of the volume chapters that they have been left as is.

Artifacts and Site Function

¶ 36 The second research objective of the Chaco Additions survey was to use surface survey artifacts to identify differences in the functions of archaeological sites. Surface remains in the form of structures and artifacts provide the basis for inferring how different types of components and features were used by their inhabitants. Frequently a variety of surface artifacts occurred in association with components and features. Assuming that surface artifacts, like architecture, can contribute to an understanding of how a site was used, the analysis explores how variation in artifact assemblages reflects differences in site use. Because component and feature typologies were derived using only morphological features, artifacts provide an excellent independent means of evaluating the functional integrity of types. In sum, analyses in this report examine the predictive relationship between architectural and morphological component and feature types and artifact assemblages.

Peripheries of Chaco

¶ 37 The final research objective of the Chaco Additions survey was to examine the canyon and its periphery as a single settlement system. Powers planned to use the Chaco Halo model as a basis from which to evaluate the settlement pattern. The intervening decades have seen an explosion of Chacoan explanatory models. Because these newer models did not guide the original research design, they are not discussed here, but they are explored in the summary chapter (Chapter 9). In Chapter 9, survey results are evaluated not only with respect to the Chaco Halo model, but also with respect to more recent approaches to understanding Chaco.

The Chaco Halo Model

¶ 38 For nearly 100 years, archaeological investigation focused intensely on central Chaco Canyon and tended to exclude surrounding areas. In the mid-1970s it was recognized that the central canyon could not be studied in isolation. A holistic understanding of the prehistoric and historic occupants of Chaco necessitated that studies include the surrounding areas (Hayes 1981; Brugge 1981; Doyel et al. 1984). The Chaco Additions survey focused on mesa tops, canyon edges, and portions of nearby drainages, providing an ideal opportunity to examine the nature of human settlement of each area as compared to Chaco Canyon. The density and longevity of Puebloan occupation in the central Canyon afford a logical basis for arguing that peripheral mesa tops and adjacent drainages were secondary settlement or resource extraction areas utilized by expanding canyon populations. By contrast, it could be argued that the peripheral areas were economically independent regions occupied as long and as intensively as the central Canyon, but providing little if any subsistence support to the largely self-sufficient central Canyon. This admittedly simplistic contrast provides a framework for examining the relationship between the canyon and surrounding areas. A third perspective entails the possibility that although the surrounding areas were continuously occupied, their relationship with Chaco changed over time, intensifying along with growth in the central canyon.

¶ 39 The “Chaco Halo,” postulated by Doyel et al. (1984), provides a starting framework for examining the resource dependent thesis. As conceived by Doyel, the halo is a sort of agricultural and resource suburb ringing Chaco in a 5-20 km radius during the Canyon cultural florescence of A.D. 975-1175. Isolated farmsteads, habitations, and in some locations entire communities such as Bis sa'ani and presumably Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola were established to provide agricultural support for the main canyon population. Inhabitants of the Canyon and halo areas formed a Chaco mega-community distinct and separate from more spatially distant outliers. Outliers within the halo such as the three communities mentioned above would have had a more direct relationship with the canyon, and perhaps were outliers only in the sense that they were outside the canyon (Doyel et al. 1984:48-52).

¶ 40 According to the halo thesis, settlement and population outside the canyon should peak during the canyon florescence. Agricultural settlements should be capable of producing surpluses for delivery to the Canyon. If halo communities were interacting closely and continuously with the Canyon, they may have enjoyed similar levels of access to exotic goods such as turquoise. Using data collected by the additions survey, each of these expectations is examined by this study. If the expectations are not supported, this will suggest a resource independent central canyon, or some other as yet unimagined canyon-periphery relationship.

Field Methods

¶ 41 The survey was designed to provide 100% coverage of all previously unserved areas. The goal was to identify and document every visible archaeological manifestation. This was accomplished by simple pedestrian survey by three or four person crews walking at intervals of 10-15 meters from each other. In flat, open terrain with good visibility, as at Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola, spacing between crew members approached the upper distance limit. In the wooded, broken terrain of Chacra Mesa, the spacing was closer to the 10 m minimum. The landscape was covered in transects oriented to the topography, with the edge crew members either picking up or laying a flagging tape or pin flag boundary. All areas, including drainage bottoms, were walked, and cliff faces and arroyo banks were examined and explored to the fullest extent possible.

¶ 42 Because virtually all hand-and-toe trails, chimneys, ledges, and alcoves were explored, it is our sense that few cliff resources were missed. A significant number of sites probably remain unrecorded due to burial by alluvial or aeolian deposits. Flood plain alluvium is present in portions of all four survey areas, especially at Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola, where the valley bottoms comprise substantial portions of each survey area. In each of these areas, Puebloan features are observable in arroyo cuts a meter or more below the present ground surface, indicating the presence of substantial post-occupational deposition and the probable existence of other buried sites. On top of Chacra Mesa, low, partially-stabilized dunes also conceal individual features as well as sites, although here, changing dune profiles and developing blowouts alternately cover and uncover portions of the buried sites. Given the undulating, fairly shallow depth of the dunes and blowouts, it seems likely that portions of most of the Chacra dune sites were recognized.

Site Delineation

¶ 43 Site boundaries were established just beyond the most distant artifacts or features, so that all materials were encompassed within the delineated area. Exceptions to this rule were artifacts occurring on steep slopes or in drainages which had obviously washed away from the site. Large areas of such “float” were often recorded as isolated occurrences. Smaller numbers of such artifacts were ignored.

¶ 44 At some very large, complex sites such as those on the dunes of Chacra Mesa, delineation was a time consuming and frustrating task. Here the presence of numerous features, and extensive, low density artifact scatters, often required intensive examination of an area several hectares in size before boundaries could be determined--and then often only on the basis of lower artifact density, rather than an absence of artifacts. Boundary lines through such low density areas are arbitrary, resulting in placement of artifacts on one side of a dividing line in one site, and those on the other side in another site. A nonsite approach involving detailed mapping of all features and artifacts within the dune area could have provided a more accurate distributional map, and a more accurate means for establishing artifact density contours, but such an effort would have required substantially more time and personnel than were available. And, because visibility was a function of blowout exposure, the accuracy of the resulting distributional windows would have been ephemeral and difficult to evaluate.

Sites and Isolated Occurrences

¶ 45 All archaeological remains identified in the field were sorted into two categories: sites and isolated occurrences. Sites had one or more structural (pueblos, hearths, hogans) or occupational features (trash mounds, sherd and lithic scatters). Single features such as hearths, cists, and storage rooms were recorded as sites. A sherd or lithic scatter containing a minimum of ten artifacts was considered to constitute an occupational feature and was recorded as a site.

¶ 46 Archaeological remains which were not part of, or associated with features as defined above were recorded as isolated occurrences (I.O.s). The I.O. category was used most frequently to record small numbers of sherds and lithics, isolated chipped or ground stone tools, scatters of sandstone slabs, cairns, isolated rock art elements, pot drops, hand-and-toe holds, and modern refuse dumps. Cultural materials found in a Flood plain, playa, or blowout adjacent to a defined site with similar materials were designated isolated occurrences if, in the judgment of the recorder, the artifacts were transported to the location by natural processes such as erosion or deflation.

¶ 47 Each site was marked with a steel rebar stake topped by a yellow plastic cap bearing a Smithsonian Institution archaeological site designation. The Smithsonian numbering system consists of a number designation indicating the state and its alphabetic position (New Mexico = 29), a letter code indicating the county (San Juan = SJ, McKinley = Mc), and finally the number of the archaeological site. The Smithsonian system was also used by Judge (1971, 1981) and Hayes (1981) in the survey of Chaco Canyon National Monument. Starting where Hayes left off, the first SJ number assigned by the Chaco Additions survey was 29SJ2404, and the first Mc number 29Mc203. The last numbers assigned were 3005 and 526 respectively. In addition to the new numbers assigned, 45 sites previously recorded by either Judge's (1972, 1981) sample survey or by Hayes’ inventory were re-recorded under their original numbers.

¶ 48 Each site was located on a 1:3000 scale black-and-white aerial photograph. The perimeter of each site was carefully drawn on the photo using visible ground features such as bushes, rocks, trees, and anthills. On most sites this provided a record of the boundary accurate to within 2-3 m. The location of the site stake was also frequently, although not systematically, marked on the photo. The aerial photo locations were subsequently transferred to enlarged topographic maps covering each area (1:12,000), enabling map plotting of site location and boundaries, with a lesser, but still reasonable level of accuracy estimated at 20+/-m. Photo and map limitations, in addition to human error, are about equally responsible for this lower level of accuracy.

¶ 49 Each site was also located in the field on a 1:24,000 topographic map, in order to provide immediate basic vocational data. If determining topographic location proved problematic, two or more compass bearings were taken to triangulate the site location. On top of Chacra Mesa, the featureless nature of the dune topography and the lack of high, short-distance features suitable for compass backsighting necessitated the erection of several 16 foot-high sighting poles. These were placed at known locations, and then were used for the necessary compass shots.

¶ 50 A wide variety of archaeological and cultural resource management data were entered on a standard site survey form at each site. Categories of information recorded include general site information, environment, condition, feature description, significance, and National Register evaluation. Blank copies of the site forms and a field manual used to guide form completion are included as Appendix 1.1. A sketch map was prepared for each site, and prominent site features were photographed.

In-field Artifact Analysis

¶ 51 In contrast with past endeavors such as Hayes' (1981) monument inventory, no artifacts were collected by the Chaco Additions survey. All artifact analyses were conducted in the field, eliminating the need to collect artifacts for future laboratory analysis and subsequent curation. Analytical procedures were designed to address specific research goals. Ceramics and lithics representative of every major definable feature of each site were analyzed. Following completion of the analysis, all sherds and lithics were rebroadcast over the site or sample unit.

¶ 52 Ceramics were the most frequent surface artifact encountered on the Puebloan sites, which account for the majority of sites recorded by the survey. Ceramics were used primarily to date the sites and to identify chronological and functional differences within sites. Reliable identification of relatively subtle chronological and functional differences required examination of a minimum of 200 sherds from each provenience.

¶ 53 At proveniences with less than 200 surface ceramics, every visible sherd was recorded. At proveniences with more than 200 ceramics, a minimum of 200 sherds, or 1 to 10% of the estimated surface sherds, was selected as the analysis sample. The average sherd count per square meter for the sample area was multiplied by the surface area of the entire feature to estimate a sherd count for the entire feature. The total number of sherds in the sample was then divided by the estimated number of surface sherds on the feature to yield the sample percent. If the initial 200 sherd sample was found to comprise less than 1% of the estimated total surface ceramic assemblage, additional transects or sample units were selected until a 1-10% sample was obtained.

¶ 54 Sample units generally consisted of linear transects one meter wide. Transects were placed judgmentally to physically cross-cut the feature and to incorporate any artifact diversity revealed in preliminary examination. Wherever possible, both sherds and lithics were recovered from a common sample area, although the sample area was expanded as necessary to recover additional sherds or lithics. At large, high density features, sample blocks were dispersed along the length of the transect to increase the probability of representing variability over the extent of the feature. A sample greater than 1% up to 10% was obtained at such features whenever possible.

¶ 55 Sherds were identified to type using the rough sort system devised by the Chaco Center for preliminary classification of excavation ceramics (Toll and McKenna 1997). Temper and vessel form were recorded. In-depth discussion of ceramic analytical procedures, the classification system, methods, and assumptions are presented in Chapter 4.

¶ 56 Lithic artifacts, although slightly less numerous than ceramic artifacts, nevertheless occurred on sites of virtually every culture and type. The presence of a relatively large number of items per provenience provided the opportunity to characterize site and provenience lithic assemblages and to investigate the distribution of exotic lithic materials. Prior analyses of materials from Chaco Center excavations indicated that a small number of exotic or nonlocal cherts occurred in greater than expected proportions at some Chaco Canyon sites (Jacobson 1984; Cameron 1984). It was not known whether exotics occurred in other Chaco Canyon sites or at outliers in similar proportions. Thus, the first goal of the lithic analysis was to investigate the distribution of exotic lithic materials. The second goal of the lithic analysis was intended to complement the ceramic analysis. No functional analysis of lithic artifacts had been performed by previous surveys. Lithic tool and flake types were documented in the hope of determining if certain combinations of flakes and tools could be predictably associated with certain ceramic assemblages and feature types.

¶ 57 In order to accomplish these goals, two variables--material type and tool type--were recorded for each flaked item analyzed. Material type was determined using a modified version of Cameron's (1997) final material groups. Selection of lithic artifacts for analysis followed the same procedures used for ceramic sampling, except that a minimum of 100 lithics was examined for each provenience. At proveniences with less than 100 lithic artifacts, every visible artifact was recorded. At proveniences with more than 100 lithics, a minimum of 100 lithics, or 1 to 10% of the estimated surface lithics, was selected using the same procedures described earlier for ceramic sampling. Methods and procedures for the lithic analysis are discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

Organization of the Report

¶ 58 The report that follows contains the original seven chapters produced for the project circa 1988 (Chapters 2-8) , as well as a summary chapter written in 2000-2001 (Chapter 9). Each of the major topical data bases presented in Chapters 2 – 8 are used as vehicles to address the original three major goals of the study, or to lay the foundation for further discussion in Chapter 9. Although readers will find some of the interpretive discussions to be dated, the information contained in the substantive chapters is expected to be of enduring value.

¶ 59 In Chapter 2, Lynne Sebastian and Jeffrey H. Altschul present and analyze the settlement pattern, site typology, and demographic data for the sites of Archaic, Anasazi, and unknown cultural affiliation. They characterize component types and their artifact assemblages over space and time within the four survey areas. They then proceed to evaluate the site typology and to analyze settlement patterns in terms of time, function, and environment. Finally, they use the settlement data to estimate survey area populations over time and evaluate the demographic implications of their results.1The components established and used in the Anasazi settlement, typology and demography analysis (Chapter 2) provide an exception to this general statement. In this chapter somewhat different criteria were used during the analysis to redefine the components established in the field. In her typology analysis, Sebastian used function, space and time to create a larger number of more discrete components. For example, at site 29SJ 342, Component 1 has a site type designation of habitation and includes five features: a roomblock, pithouse, hearth, trash mound and a possible kiva. Component 2, site type field house, includes two features, a field house and a sherd and lithic scatter. Component 3, site type scatter-with-slabs, has one feature, a slab scatter. All three components were placed in the A.D. 890-1025 date group, but because the components are spatially separate within the site, and are likely to have had different functions, they were distinguished. In contrast, for the ceramic (Chapter 4) and the lithic analyses (Chapter 5), only Components 1 and 2 were recognized (the components established in the the field), with the slab scatter included as a sixth feature of Component 1. Since most ceramic and lithic analyses were conducted at the feature level, component separation was of less concern. The details of component definition will be of little interest to many readers, but because the Chapter 2 components differ in number and composition, it is important to be aware that they are not precisely comparable to the components of Chapters 4 and 5.

¶ 60 Chapter 3, by Anne C. Cully and Mollie S. Toll, assesses the agricultural potential of the survey areas based on present topography, hydrology, vegetation, and chemical and physical soil properties. Using these attributes to map soils within each area, the quality, quantity, and distribution of arable lands are determined. Utilizing aboriginal productivity and consumption estimates, the human carrying capacity of each area is estimated.

¶ 61 In Chapter 4, Barbara J. Mills describes and analyzes the survey ceramics. The temporal, spatial, and typological aspects of the Anasazi and Navajo ceramic data bases are described, and ceramic date groups are established statistically for Anasazi ceramics. Patterns of Anasazi ceramic production and distribution are examined, and their implications for ceramic exchange are explored. Functional patterning in Anasazi ceramic assemblages is identified, and site functions are interpreted on the basis of assemblage patterns.

¶ 62 Chapter 5, by Catherine M. Cameron and Lisa C. Young, examines chipped and ground stone items documented by the survey. They describe the cultural affiliation and spatial and temporal distribution of survey lithic materials, investigate patterns of local and exotic raw material procurement, and examine patterns of technological and functional variability in lithic assemblages.

¶ 63 Chapters 6-8 are concerned with Navajo and Euro-American materials. In Chapter 6, Carol L. Gleichman presents and analyzes the data on Navajo and historic sites, settlement, and demography. She establishes a temporal framework for the analysis, and devises and tests a site typology using independent artifact and morphological data. Gleichman then examines spatial and temporal changes in settlement to determine their relationship, if any, to subsistence change and ethnic competition. Finally, she estimates Navajo population prior to the Bosque Redondo incarceration.

¶ 64 Chapter 7, by Robert Powers and Miranda Warburton presents an analysis of historic artifacts found on Navajo, Spanish-American and Anglo sites. The study of over 7,000 items poses four questions. How do artifact assemblages reflect variability over time? To what extent can ethnic affiliation be determined from artifact assemblages? How do artifact assemblages reflect differences in feature function? And, how significant is the quantity of artifacts from a given component or feature?

¶ 65 Chapter 8, by Willow Powers, provides ethnohistoric information obtained from interviews and historical records on a sample of Navajo and Euro-American sites. Occupational histories of selected sites provide a basis for discussing land use in terms of time, space, subsistence, kinship, and competition. Archaeologically derived settlement conclusions are evaluated in light of the ethnohistorical information.

¶ 66 Following the original research objectives of the study, in Chapter 9, Ruth Van Dyke and Robert Powers summarize the results of the individual studies in a culture-historical framework. The value of the survey typology is assessed based on the relationship between the morphologically derived survey typology and the activities indicated by surface artifact assemblages. Finally, the relationships of the individual survey areas to each other and to Chaco Canyon are examined in terms of the Chaco Halo model, and in terms of more recent models for understanding the Chaco experience.

Notes

1 The components established and used in the Anasazi settlement, typology and demography analysis (Chapter 2) provide an exception to this general statement. In this chapter somewhat different criteria were used during the analysis to redefine the components established in the field. In her typology analysis, Sebastian used function, space and time to create a larger number of more discrete components. For example, at site 29SJ 342, Component 1 has a site type designation of habitation and includes five features: a roomblock, pithouse, hearth, trash mound and a possible kiva. Component 2, site type field house, includes two features, a field house and a sherd and lithic scatter. Component 3, site type scatter-with-slabs, has one feature, a slab scatter. All three components were placed in the A.D. 890-1025 date group, but because the components are spatially separate within the site, and are likely to have had different functions, they were distinguished. In contrast, for the ceramic (Chapter 4) and the lithic analyses (Chapter 5), only Components 1 and 2 were recognized (the components established in the the field), with the slab scatter included as a sixth feature of Component 1. Since most ceramic and lithic analyses were conducted at the feature level, component separation was of less concern. The details of component definition will be of little interest to many readers, but because the Chapter 2 components differ in number and composition, it is important to be aware that they are not precisely comparable to the components of Chapters 4 and 5.

References

| Bannister, Bryant | |||

| 1965 | Tree-Ring Dating of the Archaeological Sites in the Chaco Canyon Region, New Mexico. Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, Technical Series 6(2):116-201. Globe, Arizona. | ||

| Bannister, Bryant, William J. Robinson, and Richard L. Warren | |||

| 1970 | Tree-Ring Dates from New Mexico A, G-H: Shiprock-Zuni-Mount Taylor Area. Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona, Tucson. | ||

| Brugge, David M. | |||

| 1981 | The Historical Archaeology of Chaco Canyon. In Archaeological Surveys of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, by Alden C. Hayes, David M. Brugge, and W. James Judge, pp. 69-106. Publications in Archeology 18A. Chaco Canyon Studies. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. | ||

| Cameron, Catherine M. | |||

| 1984 | A Regional View of Chipped Stone Raw Material Use in Chaco Canyon. In Recent Research on Chaco Prehistory, edited by W. James Judge and John D. Schelberg, pp. 137-152. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 8. Division of Cultural Research, National Park Service, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1997 | The Chipped Stone of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. In Ceramics, Lithics, and Ornaments of Chaco Canyon: Analysis of Artifacts from the Chaco Project, 1971-1978, Volume II. Lithics, edited by Frances Joan Mathien, pp. 531-658. Publications in Archaeology 18G, National Park Service, Santa Fe. | ||

| Doyel, David E., Cory D. Breternitz, and Michael P. Marshall | |||

| 1984 | Chacoan Community Structure: Bis sa'ani and the Chaco Halo. In Recent Research on Chaco Prehistory, edited by W. James Judge and John D. Schelberg, pp 37-54. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 8. Division of Cultural Research, National Park Service, Albuquerque. | ||

| Durand, Stephen R. and Kathy Roler Durand | |||

| 2000 | Notes from the Edge: Settlement Pattern Changes at the Guadalupe Community. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pages 101-109. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona, Number 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Ebert, James I., and Thomas R. Lyons | |||

| 1977 | The Role of Remote Sensing in a Regional Archaeological Research Design: A Case Study. In Remote Sensing Experiments in Cultural Resources Studies, assembled by Thomas R. Lyons, pp. 5-9. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 1, National Park Service, Albuquerque. | ||

| Fowler, Andrew, John R. Stein, and Roger Anyon | |||

| 1987 | An Archaeological Reconnaissance of West-Central New Mexico: The Anasazi Monuments Project. Unpublished ms. on file, Office of Cultural Affairs, Historic Preservation Division, Santa Fe. | ||

| Fransted, Dennis | |||

| 1979 | An Introduction to the Navajo Oral History of Anasazi Sites in the San Juan Basin Area. Navajo Aging Services, Ft. Defiance, Arizona. Unpublished ms. on file at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| Gilpin, Dennis and David E. Purcell | |||

| 2000 | Peach Springs Revisited: Surface Recording and Excavation on the South Chaco Slope, New Mexico. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pages 28-38. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Gladwin, Harold S. | |||

| 1945 | The Chaco Branch: Excavations at White Mound and in the Red Mesa Valley. Medallion Papers 33, Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona. | ||

| Hayes, Alden C. | |||

| 1981 | A Survey of Chaco Canyon Archaeology. In Archaeological Surveys of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, edited by Alden C. Hayes, David M. Brugge, and W. James Judge, pp. 1-68. Publications in Archeology 18A, Chaco Canyon Studies, National Park Service, Washington, D.C. | ||

| Hewett, Edgar Lee | |||

| 1905 | Prehistoric Irrigation in the Navajo Desert. Records of the Past 4:323-329, Washington, D.C. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1936 | The Chaco Canyon and its Monuments. Publication of the University of New Mexico and the School for American Research. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. | ||

| Hitchcock, Robert K. | |||

| 1973 | Archaeological Research Strategies: The Chaco Canyon Road Survey, Summer 1973. Unpublished ms. on file at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| Holsinger, S. J. | |||

| 1901 | Report on the Prehistoric Ruins of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Ordered by the General Land Office Letter “P”, December 18, 1900. National Archives, Washington, D. C. | ||

| Hurst, Winston B. | |||

| 2000 | Chaco Outlier or Backwoods Pretender? A Provincial Great House at Edge of the Cedars Ruin, Utah. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pages 63-78. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Irwin-Williams, Cynthia, editor | |||

| 1972 | The Structure of Chacoan Society in the Northern Southwest: Investigations at the Salmon Site — 1972. Eastern New Mexico University Contributions in Anthropology 4(3), Portales, New Mexico. | ||

| Irwin-Williams, Cynthia | |||

| 1973 | The Oshara Tradition: Origins of Anasazi Culture. Eastern New Mexico University Contributions in Anthropology 5(1), Portales, New Mexico. | ||

| Jacobson, LouAnn | |||

| 1984 | Chipped Stone in the San Juan Basin: A Distributional Analysis. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| Jalbert, Joseph Peter and Catherine Cameron | |||

| 2000 | Chacoan and Local Influences in Three Great House Communities in the Northern San Juan Region. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pp 79-90. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Judd, Neil M. | |||

| 1927 | The Architectural Evolution of Pueblo Bonito. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 13(7):561-563. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1954 | The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 124, Washington, D.C. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1959 | Pueblo del Arroyo, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 138 (1), Washington, D.C. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1964 | The Architecture of Pueblo Bonito. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 147 (1), Washington, D.C. | ||

| Judge, W. James | |||

| 1971 | Supporting Data Relating to a Proposed Archaeological Survey of the Chaco Canyon Area. UNM Proposal 101/28. Unpublished ms. on file, Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1972 | An Archaeological Survey of the Chaco Canyon Area, San Juan County, New Mexico. Final report to the National Park Service for Contract No. 14-10-7:931-51. Unpublished ms. on file, Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1973 | Paleoindian Occupation of the Central Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1979 | The Development of a Complex Cultural Ecosystem in the Chaco Basin, New Mexico. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks, Volume 2, edited by Robert M. Linn, pp. 901-906. Transactions and Proceedings Series 5, National Park Service, Washington, D.C. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1981 | Transect Sampling in Chaco Canyon — Evaluation of a Survey Technique. In Archaeological Surveys of Chaco Canyon, by Alden C Hayes, David M. Brugge, and W. James Judge, pp. 107-137. Publications in Archaeology 18A, Chaco Canyon Studies. National Park Service, Washington D.C. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1989 | Chaco Canyon-San Juan Basin. In Dynamics of Southwest Prehistory, edited by Linda S. Cordell and George J. Gumerman, pp 209-261. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. | ||

| Kantner, John and Nancy M. Mahoney, editors | |||

| 2000 | Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Kendrick, James W. and W. James Judge | |||

| 2000 | Household Economic Autonomy and Great House Development in the Lowry Area. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pages 113-129. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

| Kidder, Alfred V. | |||

| 1924 | An Introduction to the Study of Southwestern Archaeology with a Preliminary Account of the Excavations at Pecos. Papers of the Southwest Expedition 1. Reprinted in 1962 by Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1927 | Southwestern Archaeological Conference. Science 66 (1716): 489-491 | ||

| Kincaid, Chris, editor | |||

| 1983 | Chaco Roads Project Phase I: A Reappraisal of Prehistoric Roads in the San Juan Basin. Bureau of Land Management, Albuquerque. | ||

| Kluckhohn, Clyde | |||

| 1967 | Navajo Witchcraft. Beacon Press, Boston. | ||

| Lekson, Stephen H., Thomas C. Windes, and Peter J. McKenna | |||

| 2006 | Architecture. In The Archaeology of Chaco Canyon: An Eleventh-Century Pueblo Regional Center, edited by Stephen H. Lekson, pp. 67-116. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe. | ||

| Lister, Robert H. and Florence C. Lister | |||

| 1981 | Chaco Canyon Archaeology and Archaeologists. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. | ||

| Lyons, Thomas R. and Robert K. Hitchcock | |||

| 1977 | Remote Sensing Interpretation of an Anasazi Land Route System. In Aerial Remote Sensing Techniques in Archaeology, edited by Thomas R. Lyons and Robert K. Hitchcock, pp. 111-134. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 2. National Park Service and University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| Lyons, Thomas R., Basil G. Pouls, and Robert K. Hitchcock | |||

| 1972 | The Kin Bineola Irrigation Study: An Experiment in the Use of Aerial Remote Sensing Techniques in Archaeology. In Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference on Remote Sensing in Arid Lands, pp. 266-283. University of Arizona, Tucson. | ||

| McNitt, Frank | |||

| 1957 | Richard Wetherill: Anasazi. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. | ||

| Marshall, Michael P., David E. Doyel, and Cory Dale Breternitz | |||

| 1982 | A Regional Perspective on the Late Bonito Phase. In Bis sa'ani: A Late Bonito Phase Community on Escavada Wash, Northwest New Mexico, Volume 3, edited by Cory Dale Breternitz, David E. Doyel, and Michael P. Marshall, pp. 1227-1240. Navajo Nation Papers in Anthropology 14. Navajo Nation Cultural Resource Management Program, Window Rock, Arizona. | ||

| Marshall, Michael P., John R. Stein, Richard W. Loose, and Judith E. Novotny | |||

| 1979 | Anasazi Communities of the San Juan Basin. Public Service Company of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and New Mexico Historic Preservation Bureau, Santa Fe. | ||

| Martin, Paul S. | |||

| 1936 | Lowry Ruin in Southwestern Colorado. Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropological Series 23(1), Chicago. | ||

| Mills, Barbara J. | |||

| 2002 | Recent Research on Chaco: Changing Views on Economy, Ritual, and Society. Journal of Archaeological Research 10 (1):65-117. | ||

| Morris, Earl H. | |||

| 1939 | Archaeological Studies in the La Plata District: Southwestern Colorado and Northwestern New Mexico. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 519. Washington, D.C. | ||

| Morrison, C. C. | |||

| 1876 | Executive and Descriptive Report of Lieutenant C. C. Morrison, Sixth Cavalry, on the Operation of Party No. 2, Colorado Section, Field Session 1875. Appendix E in Annual Report Upon the Geographical Surveys West of the One-Hundredth Meridian, in California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona and Montana, by George M. Wheeler, Being Appendix JJ of the Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers for 1876, pp. 136-147. House Exec. Doc. I, Part 2, 44th Congress, 2nd Session, Washington, D.C. | ||

| Nials, Fred, John Stein and John Roney | |||

| 1987 | Chacoan Roads in the Southern Periphery: Results of Phase II of the BLM Chaco Roads Project. Cultural Resource Series No. 1, Bureau of Land Management, Albuquerque. | ||

| Pepper, George H. | |||

| 1909 | The Exploration of a Burial Room in Pueblo Bonito, New Mexico. In Anthropological Essays Presented to Frederick Ward Putnam in Honor of His Seventieth Birthday, pp. 196-252. G.E. Stechert and Company, New York. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1920 | Pueblo Bonito. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume 27. New York. | ||

| Powers, Robert P., William B. Gillespie and Stephen H. Lekson | |||

| 1983 | The Outlier Survey: A Regional View of Settlement in the San Juan Basin. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 3. National Park Service, Albuquerque. | ||

| Reichard, Gladys A. | |||

| 1944 | The Story of the Navajo Hail Chant. Columbia University Press, New York. | ||

| Roberts, Frank H. H., Jr. | |||

| 1932 | The Village of the Great Kivas on the Zuni Reservation, New Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 111. Washington, D.C. | ||

| Roney, John R. | |||

| 1992 | Prehistoric Roads and Regional Integration in the Chacoan System. In Anasazi Regional Organization and the Chaco System, edited by David E. Doyel, pp 123-132. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology Anthropological Papers 5, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. | ||

| Toll, H. Wolcott and Peter J. McKenna | |||

| 1997 | Chaco Ceramics. In Ceramics, Lithics, and Ornaments of Chaco Canyon: Analysis of Artifacts from the Chaco Project, 1971-1978, Volume I. Ceramics, edited by Frances Joan Mathien, pp. 17-530. Publications in Archaeology 18G, Chaco Canyon Studies. National Park Service, Santa Fe. | ||

| Van Dyke, Ruth M. | |||

| 1999a | The Andrews Community: An Early Bonito Phase Chacoan Outlier in the Red Mesa Valley, New Mexico. Journal of Field Archaeology 26(1): 55-67. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1999b | The Chaco Connection: Evaluating Bonito Style Architecture in Outlier Communities. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 18(4):471-506. | ||

| Vivian, R. Gwinn | |||

| 1970a | An Inquiry into Prehistoric Social Organization in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. In Reconstructing Prehistoric Pueblo Societies, edited by William A. Longacre, pp. 59-83. School of American Research Book, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1970b | Aspects of Prehistoric Society in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Unpublished Ph.D Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1997 | Chacoan Roads: Morphology. Kiva 63(1):7-34. | ||

| ---- | |||

| n.d. | Chacoan Water Control Systems: Form, Function, and Organization. Ms. in preparation. | ||

| Warburton, Miranda, and Donna K. Graves | |||

| 1992 | Navajo Springs, Arizona: Frontier Outlier or Autonomous Great House? Journal of Field Archaeology 19(1):51-69. | ||

| Windes, Thomas C. | |||

| 1978 | Stone Circles of Chaco Canyon, Northwestern New Mexico. Reports of the Chaco Center, Number 5. National Park Service, Albuquerque. | ||

| ---- | |||

| 1987 | Investigations at the Pueblo Alto Complex, Chaco Canyon New Mexico, 1975-1979, Volume I, Summary of Tests and Excavations at the Pueblo Alto Community. Publications in Archeology 18F, Chaco Canyon Studies. National Park Service, Santa Fe. | ||

| Windes, Thomas C., Rachel M. Anderson, Brian K. Johnson, and Cheryl A. Ford | |||

| 2000 | Sunrise, Sunset: Sedentism and Mobility in the Chaco East Community. In Great House Communities Across the Chacoan Landscape, edited by John Kantner and Nancy M. Mahoney, pp 39-59. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona 64, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. | ||

Appendices

Appendix 1.1 Site Record Forms and Guidebook for Completing Forms

¶ 67 Appendix 1.1 (http://www.chacoarchive.org/media/book/minishowcase/) is a copy of the guidelines and blank forms for recording site data from field work at Chaco Culture National Historical Park.