Previous | Table of Contents | Next

7.

Historic Artifacts of the Chaco Additions Inventory Survey

Robert P. Powers and Miranda Warburton

¶ 1 The historic artifacts recorded by the Chaco Additions Inventory Survey are a diverse if often prosaic mix of items ranging from Native crafted pottery and stone tools to mass-produced automobile parts and prescription eyeglass lenses. Our goal in this chapter is to provide a brief description and analysis of this historic material culture in a fashion that enhances the perspectives of the preceding Navajo and historic site settlement and succeeding Navajo ethnohistory chapters. Approximately 363 historic period sites, including Navajo, Spanish-American and Anglo components were identified by the survey, although of this total only 191, or slightly more than half of the historic sites had historic artifacts of any kind.

¶ 2 Nonetheless, a total of over 7,000 historic artifacts, including Navajo and historic Puebloan pottery, chipped and ground stone, Euro-American manufactured items, and a variety of other artifacts were observed and recorded. Because considerable time and effort was expended in documenting the proveniences of the artifacts, the emphasis in the following pages is on the contexts — the components and features — in which the artifacts were documented. As described in Chapter 1, a component is the portion of a site assigned to the same culture and site type. Most of the discussion in this chapter is at the component level since we are interested only in the Navajo and historic period portions or components of a site. Each component, in turn, is composed of one or more features. Features range from constructed features such as a sweat lodge, to refuse features consisting of a cluster of artifacts, such as a Euro-American refuse scatter. The site type is simply a classificatory label used to sort the components into functional groups. For example, single habitation, stockholding, and rock art are site type designations given to components. In the following pages we use component and feature assemblages to show both the possibilities and limitations of artifacts as indicators of the use or function of these proveniences.

¶ 3 Four specific questions are posed. How do the artifact assemblages reflect variability over time? To what extent can ethnic affiliation be determined from artifact assemblages? How do the artifact assemblages reflect differences in feature function? And, how significant is the quantity of artifacts from a given component or feature?

¶ 4 The answers to these questions may be summarized as follows. First, artifact assemblages reflect variability by changing in size and composition over time. The types of artifacts present, as well as the number of artifacts, changes significantly.

¶ 5 Second, determination of ethnic affiliation from artifact assemblages for this group of components is not possible. Third, and contrary to expectation, artifact assemblages do not appear to reflect differences in feature function beyond a general level. Assemblage variability often seems to correlate closely with size.

¶ 6 Fourth, and last, the quantity of artifacts appears to be a key indicator of how long individual components were occupied, and how the survey areas were used over time. The reliability of inferences about function is greater at a small number of components with more artifacts.

¶ 7 The organization of the chapter is as follows. First, we provide an overview of previous historic artifact studies in the Chaco area in order to gain an informed perspective on past work and to see how this study differs in its approach. Following this, we describe the methods used in the investigation. Next, the overall artifact assemblage is described and the analysis of the artifacts is presented. The final section, the summary and conclusions, provides a detailed discussion of the study conclusions.

Background

¶ 8 Studies of historic artifacts undertaken in the general Chaco region prior to the current survey include Brugge (1981b, 1986), Duran and McKeown (1980), Gilpin (1983a, 1983b), Kelley (1982), Kelley and Boyer (1982), and Ward et al. (1977) among others. Brugge’s descriptions of historic artifacts recovered or documented by the National Park Service’s inventory of Chaco Canyon National Monument (Brugge 1981b) and in his own survey of Navajo sites of the Tsegai or Chaco Canyon area (1986) are particularly relevant. One of the Tsegai Navajo winter habitation sites (Site K) documented by Brugge was also recorded by the Additions Survey as 29SJ 2966. This site’s large artifact assemblage in combination with informant data provided by previous residents of the site make it an ideal place to evaluate feature and artifact relationships.

¶ 9 In contrast to the present analysis, Brugge’s Tsegai study (1986) analyzes categories of artifacts such as ceramics and Euro-American trade goods from a site or group of sites rather than examining the artifacts on a provenience or feature basis. Brugge’s approach is extremely useful in looking at the assemblage as a whole but focuses less on component or structure specific activity.

¶ 10 The Duran and McKeown (1980) study of Navajo sites in the Gallegos Mesa area of the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project area (located about 50 km north of Chaco) has become a standard reference for historic artifact studies in New Mexico because, in addition to their analysis, they provide detailed information on product brands, can and bottle technology, and the production spans of Euro-American artifacts. A total of 16 Navajo sites dating from 1915 to 1976 were included in their research. Like Brugge (1986), they analyze artifacts primarily by material category. A brief discussion of the kinds of artifacts that characterized Navajo activity areas is also included (Duran and McKeown 1980:1136, 1147).

¶ 11 Gilpin’s (1983a, 1983b) studies were also undertaken on Gallegos Mesa as part of the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project. Gilpin (1983a, 1983b) provides an extremely thorough examination of 10 excavated historic sites selected from some 199 historic components at 375 separate sites (Gilpin 1983a:984). Over 13,000 artifacts were analyzed from these 10 sites (Gilpin 1983a:1005). In addition to summarizing the artifacts recovered, Gilpin discusses each site individually, providing ethnographic and historic data as well as detailed descriptions of the artifacts. He also presents inter-site comparisons and attempts to infer function or identify activities from the various assemblages at the 10 sites (1983b). His analysis is particularly detailed because of the temporal and spatial control provided by site excavation and the in-depth scrutiny of artifacts allowed by laboratory analysis.

¶ 12 Kelley’s (1982) report on the Chaco Canyon Ranch is an detailed ethnohistorical study of the 67 km2 (26 mi2) Gallo Wash Mine Lease to the immediate north and east of the Chacra Mesa survey area. The Chaco Canyon Ranch study analyzed survey data on 78 historic period site components. These components were the products of four groups of people: large-scale Navajo stock owners, small-scale Navajo stock owners, shepherds who worked for Ed Sargent, and oil-drilling crews (Kelley 1982:iii). Kelley’s analysis, although primarily economic in nature, addresses questions of assemblage diversity from both a synchronic and diachronic perspective. Archeological information, ethnographic interviews, archival sources, as well as available literature, were utilized in compiling the impressive Chaco Canyon Ranch study. Like the Navajo ethnohistory study conducted for the Chaco Additions areas (see Chapter 8), Kelley was able to identify the occupants of individual sites. Kelley’s (1982:342-346) cautions to archeologists relying solely on archeological information to investigate ethnicity and site use are well placed and are underscored by the complex use histories of some the sites described by Willow Powers in Chapter 8. Both studies illustrate the difficulty, if not impossibility, of determining ethnic affiliation without complementary ethnohistoric studies.

¶ 13 Kelley and Boyer’s (1982) report on historic sites in the McKinley Mine Area northwest of Gallup, New Mexico, discusses the methods and results of their analysis of 1,334 artifacts from 34 sites. Similar to Brugge’s (1986) and Duran and McKeown’s (1980) investigations, this report emphasizes categories of artifacts such as plastic and leather, and functional groupings of artifacts such as personal effects and entertainment, rather than looking at specific proveniences vis-a-vis their artifactual assemblages.

¶ 14 The Ward et al. study (1977) presents the analysis of artifacts from historic sites in the Lower Chaco River area about 75 km northwest of Chaco. The authors examine material culture remains from 335 of 413 Navajo components (Ward et al.1977:229). Like Duran and McKeown (1980), they provide lists of brands and illustrations of bottles and jars useful for analysis (Ward et al. 1977:231-240). They also discuss the material remains in relation to functional categories of artifacts such as food stuffs and personal effects.

¶ 15 All of the above studies have contributed in some way to the research at hand. Some of the reports were helpful for the present artifact analysis, while others provide an alternative perspective for viewing the Chaco Additions assemblage.

Methods

¶ 16 Analysis of the historic artifacts from the sites included in the Chaco Additions Survey was undertaken in three stages. The first stage took place in the field where personnel recorded but did not collect historic artifacts. Historic artifacts were encountered in a wide variety of contexts; for example, at an Anasazi watercontrol site, a few pieces of historic trash might also be found. Much more common were Navajo components with one or more features and a small number of historic artifacts in a low density scatter covering the area. Also present, but less frequent were components with several hogans, ash heaps, a variety of other features, and dozens of historic artifacts.

¶ 17 At components with few artifacts, the site form artifact descriptions are often more detailed; at the larger components, field personnel occasionally resorted to less detailed descriptions such as “lots of pieces of bone in ash heap #7.” In general, however, the Stage 1 artifact descriptions are fairly detailed. Copies of the survey record forms, including the historic artifact descriptions are available through the Chaco Digital Archive (http://www.chacoarchive.org/cra/survey-data/).

¶ 18 While there were no specific standards for recording historic artifacts, artifacts were usually described in some detail. For example, manufacturer’s marks were noted, can types and openings were recorded, and all artifacts were included on the site forms accompanied by brief descriptions of their potentially diagnostic attributes. Recorders also often indicated the condition of the item and whether it had been modified for reuse. An analysis of the adaptive uses of Euro-American mass produced items would have been a worthy addition to the study, but unfortunately it was beyond our means.

¶ 19 None of the field recorders was a specialist in historic artifact identification or dating, and because artifacts were not collected for lab analysis, the quality and specificity of the identifications are less than they would have been had the items been collected and analyzed by a historic archeologist expert in 20th century consumer technology. While this is regrettable, it had the intended effect of preserving the artifacts in their original on-site contexts, where they remain available for future researchers.

¶ 20 The Stage 2 analysis was conducted by Henry Walt in 1985 to 1986. It consisted of dating the artifacts based on the descriptions given in the site forms. The analyst was not in the field, and relied solely on artifact descriptions from the site forms. Based on the artifact descriptions, Walt assigned each artifact a beginning and an end date whenever possible. Artifact identification was aided by previous studies of historic artifacts in the San Juan Basin (discussed in the Background section).

¶ 21 Unfortunately, the lack of precise information about many artifacts prohibits assignment of exact dates, and thus many date ranges simply reflect the beginning and end production dates for glass colors or can manufacturing techniques. For example, an assemblage consisting of a few pieces of brown glass dating from 1880 to the present provides only the most general time range for a component that may have been occupied for only a few days. Although field personnel provided the best observations possible, close dating of glass and can artifacts was often limited by the absence of portions of the item that could have revealed the manufacturing techniques used to produce or it, or that contained company trademarks needed for more precise identification.

¶ 22 Nonetheless, because cans and glass make up the majority of historic artifacts recorded on the Chaco Additions Survey and are the most thoroughly studied classes of artifacts, they were the most useful in dating. Vicks and Mentholatum jars, for example, were often helpful in dating survey components; Ball freezer jars, medicine bottles, and soda pop bottles were also useful.

¶ 23 In a number of instances tree-ring dates, ethnohistoric information provided by Navajo informants and name and date inscriptions fruitfully supplemented the dates derived from the artifacts (see Appendix 6.1, Table 2). In addition to glass and cans, other artifactual remains identified on the project include bone, ceramics, fiber, leather, metal, plastic, rubber, stone, wood, and some paper. With the exception of Navajo and historic Puebloan pottery, many of these materials are much harder to date and identify. Wherever possible beginning and end dates are provided for these items as well.

¶ 24 This report comprises Stage 3 of the analysis. The chapter has been prepared based on information from the site survey forms, the Stage 2 analysis, the Navajo and Historic site settlement chapter (Chapter 6), and the ethnographic chapter (Chapter 8). Appendix 7.1 prepared by Warburton is the historic refuse database which provides site, provenience, basic artifact, and date information for Euro-American artifacts. It does not include Navajo or historic Puebloan ceramics or chipped and groundstone artifacts found on historic components.

Analysis

¶ 25 Approximately 7,186 historic artifacts were observed and recorded by the survey (Table 7.1). The great majority came from 191 Navajo, Spanish-American or Anglo sites. A few historic artifacts (n=108; 1.5 percent) were also found on 49 prehistoric sites with no other historic material. In most instances the historic artifacts at these sites are limited to one or a few items (Appendix 7.2). Isolated occurrences of historic items on prehistoric sites, as well as isolated artifacts across the survey area landscape can be attributed to extensive use of all of the survey areas by Navajo and Spanish-American sheepherders whose widespread stock raising activities have left a veneer of 20th century artifacts virtually everywhere.

Table 7.1. Historic artifacts by assemblage groups and material class.

¶ 26 In order to aid examination of individual assemblages, the 191 sites were sorted into three groups based on size and the presence or absence of Native and Euro-American artifacts. Assemblages containing Native artifacts only were placed in one group (Appendix 7.3), while the more numerous assemblages containing a combination of Native and Euro-American artifacts or Euro-American artifacts exclusively, were divided into two additional groups, one consisting of assemblages with 20 or fewer artifacts (Appendix 7.4), and a second containing those with more than 20 artifacts (Appendix 7.5).

¶ 27 The first group of assemblages with Native artifacts only includes 60 sites with 2,106 artifacts, accounting for 29 percent of the total historic artifact assemblage (Table 7.1). The second group of eighty-seven sites, with assemblages of 20 or fewer total artifacts, includes those with Native and Euro-American, or Euro-American artifacts only. It contains 580 items, or about 8 percent of all historic artifacts. The assemblages from this second group are referred to in the following pages as small mixed assemblages.

¶ 28 The third group of 44 sites, with assemblages of more than 20 artifacts of both Native and Euro-American items or only Euro-American items, contains 4,392 artifacts, or 61 percent of the total historic assemblage (Table 7.1). The assemblages in this third group are referred to as large mixed assemblages. In addition to presenting the assemblage of each site, Appendices 7.3, 7.4, and 7.5 provide information on survey area, site type, feature type, the estimated date range of each artifact, an estimated date of the component (based on artifacts only), the chronological periods represented, and an overall component date. The site types and the chronological periods (A.D. 1600-1700, 1700-1863, 1868-1930, 1930-1980) shown in the appendices and the tables follow Gleichman (see Table 6.1, Appendix 6.1, Tables 1 and 2) unless otherwise indicated in order to maintain concordance between the chapters.

Artifact Assemblage Attributes

Assemblage Cultural Affiliation

¶ 29 While Navajo sites account for the great majority of the components with historic refuse, evidence of Spanish American and some Anglo use was indicated at 21 sites1All but one of the Spanish-American components were identified by name and date inscriptions, as were two of the three Anglo components. The site with Spanish-American and Anglo components had both Spanish-American and Anglo inscriptions. One of the Spanish-American components was identified by Navajo informant data. The remaining Anglo component, a historic coal mine, was known to have been used by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the 1930s. Gleichman (Appendix 6.1, Table 9) notes that 221 inscriptions, of which the great majority are Spanish surnames, were found at 68 sites. Although they range in date from 1881-1981, 75 percent of the dates fall between 1916-1945, the period of intensive Spanish-American herding in the Chaco Additions areas.. Seventeen of the 21 were Spanish-American, three were Anglo, and one was used by both Spanish-Americans and Anglos. Since Spanish-American and Anglo use was archaeologically visible only through name and date inscriptions, it is likely that Euro-American use at other sites remains undetected. Most of the sites with name and date inscriptions were also used by Navajos. An example of this is site 29SJ 2459, a Navajo summer habitation in the Kin Klizhin survey area, which according to Navajo informants, was used extensively by Spanish-American herders after its Navajo occupants left (Appendix 8.1). In view of cases like this, it is probable that a substantial number of sites post-dating the arrival of Spanish-American herders (the earliest inscriptions with Spanish surnames date to the 1880s; see Brugge 1980:108-109, 118, 156-157; Kelley 1982:45-47) were used both by Navajos and Spanish-Americans. Because both were outfitted with mass produced Euro-American goods, it was not possible to analyze the artifact assemblages by cultural group (see also Brugge 1981b:97).2Of the 21 Spanish-American and Anglo components, four had only Navajo or historic Pueblo artifacts, but the remaining 17 had mixed assemblages of Native and Euro-American artifacts, or Euro-American artifacts only. Because 14 of the 17 components also had Navajo occupations it was impossible to determine who the Euro-American artifacts were used by. Although inscriptions of individuals with non-Spanish surnames were rare, Anglo ranchers played an outsized role in the use of the survey areas, initially by leasing or purchasing land, and later by controlling access to it through fencing. From the 1920s onward an increasing number of the Navajo and Spanish-American sheepherders using the survey areas were working for local Anglo ranchers such as Ed Sargent.

Assemblages by Survey Area

¶ 30 As indicated in Table 7.2 relatively few sites with historic artifact assemblages were present in the Kin Klizhin (n=13), Kin Bineola (n=14), and South Addition (n=10) survey areas. Cumulatively, the sites in these areas account for less than 7 percent of the historic artifacts. Several sites in the Kin Klizhin, Kin Bineola, and South Addition areas had Native only assemblages, and of these, one in the Kin Bineola area, and another in the South Addition may have seen use between 1800-1900. Of the sites with small or large mixed assemblages, only one, a temporary shelter in the South Addition was clearly occupied prior to 1900. Nineteenth century use of this site is indicated by 1881 date inscriptions.

|

Table 7.2. Assemblage groups by survey area. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assemblage Group | Kin Klizhin | Kin Bineola | Chacra Mesa | South Addition | Total |

| Native Artifacts | |||||

| # of Sites | 1 | 2 | 54 | 3 | 60 |

| # of Artifacts | 2 | 60 | 1,942 | 102 | 2,106 |

| 20 or Fewer Artifacts | |||||

| # of Sites | 10 | 12 | 61 | 4 | 87 |

| # of Artifacts | 46 | 53 | 456 | 25 | 580 |

| More than 20 Artifacts | |||||

| # of Sites | 2 | 39 | 3 | 44 | |

| # of Artifacts | 104 | 4,197 | 91 | 4,392 | |

| Total | |||||

| # of Sites | 13 | 14 | 154 | 10 | 191 |

| # of Artifacts | 152 | 113 | 6,595 | 218 | 7,078 |

| Artifact % | 2.1 | 1.6 | 93.2 | 3.1 | 100 |

¶ 31 The overwhelming majority of artifacts (n=6,595; 93 percent) were found on sites in the Chacra Mesa survey area, which was used over a long span of time extending from the 17th century through to the early 1950s. Because relatively few artifacts were found in the Kin Klizhin, Kin Bineola, and South Addition survey areas we did not attempt to compare assemblages between the four areas.

Assemblage Material Classes

¶ 32 A breakdown of the 7,186 historic artifacts into gross material classes shows that approximately 3,062 (43 percent) are historic sherds from vessels of either Navajo or historic Pueblo manufacture, 1,131 (16 percent) are chipped or ground stone artifacts, and 2,779 (39 percent) are 20th century Euro-American manufactured items of steel, glass, rubber, plastic, leather or ceramic materials (Table 7.1). Another 131 miscellaneous items (2 percent) include burned and unburned bone, shell, beads, turquoise, wood, corn cobs, selenite, unworked pebbles, and fossils. Finally, 83 sherds (1 percent) of Anasazi manufacture were also found on historic features where they appear to have been curated by historic period inhabitants.

¶ 33 The frequencies and proportions of the historic ceramics are shown by ware, type, and vessel form in Table 7.3. Similar inventories of the lithic artifacts, Euro-American manufactured items, miscellaneous artifacts, and Anasazi ceramics found on Navajo and historic period sites are presented in Tables 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, and 7.7, respectively.

Table 7.3. Navajo and historic Pueblo ceramic types by vessel form.

Table 7.4. Lithic materials at Navajo and historic components.

Table 7.5. Euro-American manufactured materials at Navajo and historic components.

Table 7.6. Miscellaneous materials at Navajo and historic components.

Table 7.7. Anasazi ceramics by vessel form at Navajo and historic period components.

Assemblage Size

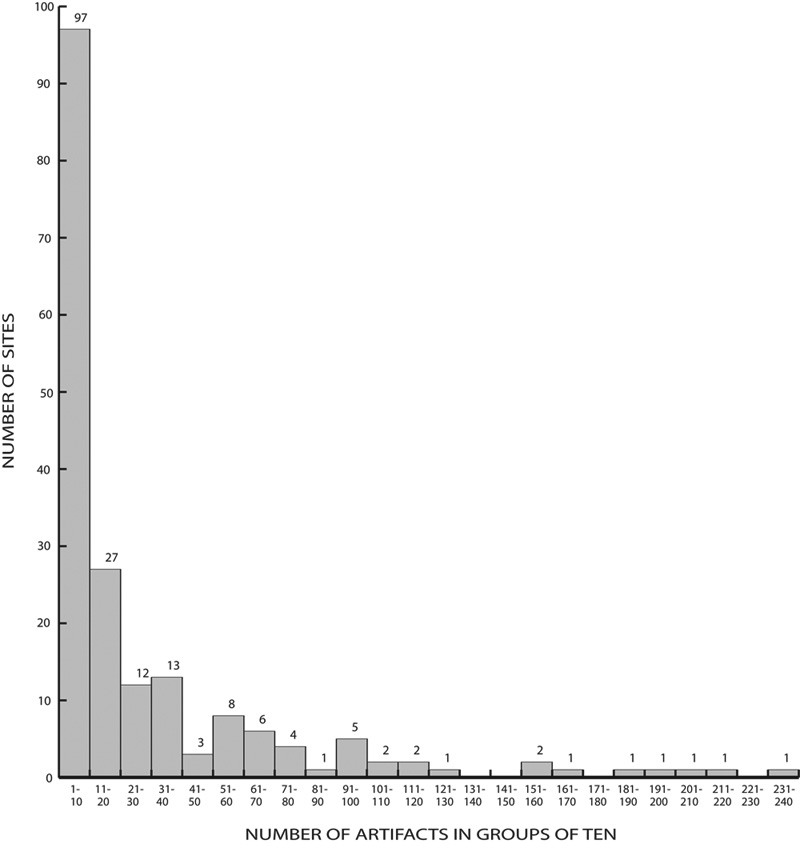

¶ 34 If the 7,078 historic artifacts found at sites with historic components were evenly divided among the 191 sites, the average historic component would contain 37 artifacts. However, as shown in Figure 7.1, the distribution of assemblage is strongly skewed to small assemblages. Fifty-one percent of all components have 10 or fewer artifacts, 78 percent have 40 or fewer artifacts, and another 14 percent have assemblages ranging in size from 41 to 100 items. The remaining 8 percent have a 101 or more artifacts. Two outliers, not shown in Figure 7.1 are sites 29SJ 2655 (327 items) and 29SJ 2966 (1,305 items). 29SJ 2966, which accounts for 18 percent of all the historic period artifacts will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

|

Figure 7.1. Assemblage size (in groups of 10 artifacts) by number of sites. |

¶ 35 Examination of assemblage size over time (Table 7.8) shows that 41 assemblages dating prior to the five year period of Navajo internment at Bosque Redondo (1863-1868) have a mean of 56 artifacts (n= 2,314; s.d. =71.0), while 113 components occupied after the 1868 return from Bosque Redondo had a mean of only 29 artifacts (n=3,328; s.d.=123.8).3Although most analyses in the chapter divide the post-Bosque Redondo period into two time intervals (1868-1930 and 1930-1980) many post-1868 components were occupied during some or all of both periods, making it difficult to obtain a clear picture of assemblage size in either period. Potsherds and pieces of broken glass were counted as individual artifacts since the number of ceramic vessels or glass containers represented was often unknown. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test comparing the median number of artifacts in the two periods rejects the null hypothesis that the medians are not significantly different (W= 4330.5, p < 0.001).4Because the artifact count data could not be transformed to a normal distribution, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used. For Mann-Whitney the artifact counts are converted to ranks. To do this all the values are converted to ranks of one to n (n being the total number of values), with one being the lowest. The ranks between the two time periods were then compared. Changes in length of site occupation and land use, discussed later in the chapter, may be responsible for the reduced size of the average artifact assemblage in the post-1868 period.

|

Table 7.8. Assemblage size by time period and site type. |

||

|---|---|---|

| Site Type/Statistic | Pre-1863 | Post-1868 |

| All Components | ||

| Number of Artifacts | 2,314 | 3,328 |

| Number of Cases | 41 | 113 |

| Mean Assemblage Size | 56.4 | 29.5 |

| Median Assemblage Size | 32 | 7 |

| Standard Deviation | 71.0 | 123.8 |

| Habitation | ||

| Number of Artifacts | 1,029 | 1,208* |

| Number of Cases | 14 | 32 |

| Mean Assemblage Size | 73.5 | 37.8 |

| Median Assemblage Size | 35 | 20.5 |

| Standard Deviation | 77 | 36.5 |

| Temporary Camps | ||

| Number of Artifacts | 847 | 418 |

| Number of Cases | 17 | 41 |

| Mean Assemblage Size | 49.8 | 10.2 |

| Median Assemblage Size | 31 | 5 |

| Standard Deviation | 74.8 | 11 |

| Special Use | ||

| Number of Artifacts | 426 | 397 |

| Number of Cases | 9 | 39 |

| Mean Assemblage Size | 47.3 | 10.2 |

| Median Assemblage Size | 26 | 4 |

| Standard Deviation | 58.3 | 17.2 |

| * Site 29SJ 2966 has been excluded from the Post-1868 habitation components due to its large artifact count. With it, the total artifact count is 2,513 items, the mean assemblage size is 76.2 artifacts and the standard deviation is 223.5. | ||

¶ 36 To determine if the assemblages associated with the three major site types — habitations, temporary camps, and special use components — were significantly different from each other, the sizes of these assemblages were compared to each other in each time period. For the pre-1863 period, a Kruskal-Wallace test5The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallace test also compares ranking between sample populations but is used to compare three or more samples, or in this case, the three major site types. comparing the median artifact assemblage size showed no significant statistical differences between the three site types, confirming the null hypothesis that the medians are not significantly different (H= 1.06; df =2; p = 0.588).

¶ 37 In contrast, for the post-1868 period, a Kruskal-Wallace test comparing the three site types rejected the null hypothesis that the medians are not significantly different (H= 17.26, df = 2, p<0.001). The similarity of the pre-1863 assemblages is in marked contrast to the differences between the post-1868 assemblages which appear to reflect growing assemblage size distinctions between habitations, temporary camps and special use components over time.

Assemblage Change Over Time

Artifact Groups by Time Period

¶ 38 The Native, small mixed and large mixed assemblage groups provide a useful starting point for examining historic artifact assemblages over time. Table 7.9 shows the chronological spread of historic artifact assemblages composing the artifact groups. Two early components date between 1600-1700, while 58 components (23 percent) with artifact assemblages date to the 1700-1863 period. Larger numbers of components have assemblages in the succeeding 1868-1930 (n=85; 34 percent) and 1930-1980 (n=82; 33 percent) time periods. Twenty-one components are of unknown date. Overall, the table shows that an expanded number of components have artifact assemblages after 1868.

Table 7.9. Artifact groups by time period.

¶ 39 A more fine-grained picture of the nature of these assemblages is obtained by combining the material class information in Table 7.1 with the temporal distribution data in Table 7.9. At Native artifact assemblages, pottery is dominant, accounting for nearly 70 percent of the artifacts. Ceramics include Navajo plain or painted wares and historic Puebloan trade wares. Flaked and groundstone items account for the remaining 30 percent, although as will be discussed later, this proportion probably under-represents the true proportion of stone artifacts. One-quarter of the components with Native only artifact assemblages are of unknown date. Inability to assign a date is usually the product of either unidentifiable pottery, the presence of only one or a few sherds or the complete absence of ceramics. Native only components that could be assigned to one of the time periods generally have Navajo or Historic Puebloan ceramics and were given time period assignments reflecting the production date ranges of the ceramics. Nearly 54 percent of the datable components pre-date 1863, while only 21 percent post-date the 1868 return from Bosque Redondo. Given the absence of Euro-American artifacts, it seems likely that most of the latter components date to the decades immediately following Navajo resettlement. Only five components post-date 1930, and at each of these the relatively late date is based on Navajo informant data or name and date inscriptions, rather than the few ceramics present.

¶ 40 The small mixed assemblages include some Navajo and Historic Pueblo pottery as well as chipped and ground stone and a few other items, but Euro-American artifacts are dominant, accounting for about 82 percent of all the items present (Table 7.1). As Table 7.9 shows, these assemblages are generally later in date than the Native assemblages. Whereas nearly 54 percent of the Native assemblages pre-dated 1863, only about 6 percent of the mixed assemblages do. These early mixed assemblages appear to reflect multiple occupations with early use indicated by pottery or tree-ring dates, followed by 20th century re-occupation marked by Euro-American artifacts.

¶ 41 The majority of the small mixed assemblages date to the 1868-1930 (41 percent) and 1930-1980 (49 percent) time groups. In contrast, only about 13 percent (1868-1930) and 7 percent (1930-1980) of the Native only assemblages date to these periods (Table 7.9).

¶ 42 The large mixed assemblages incorporate aspects of both the Native and small mixed assemblages. Like the latter, these assemblages often contain Navajo and historic Pueblo pottery, chipped and ground stone, other materials, and Euro-American artifacts, but unlike them, Native artifacts compose a substantial proportion (35 percent) of the assemblage, although by no means matching the proportion of Euro-American artifacts (50 percent) (Table 7.1). This more integrated mix of Native and Euro-American materials is a clue to the dating of the assemblages. Twenty-four percent were occupied during the 1700-1863 period, 43 percent in the following 1868-1930 interval, and 33 percent in the 1930-1980 period (Table 7.9). All 44 large mixed assemblage components (Table 7.1) were occupied during a total of 75 time periods (Table 7.9), illustrating that many of these components were occupied during portions of two or three time periods, a fact that does much to explain the larger size and more varied composition of their assemblages.

Site Types by Time Period

¶ 43 It is also important to have an understanding of the kinds of components where assemblages were found, and how the proportions of these change over time. As was seen in Chapter 6, site types provide important clues to how the survey areas were used. The components are divided into three major types, habitations, temporary camps and special use. Habitations are winter or summer camps with one or more hogans, used for the season by an extended or nuclear family as its primary residence. Although these sites are often referred to in the literature as “camps,” they have been termed habitations to distinguish them from temporary camps which were occupied only by a portion of the family on a short-term basis. Temporary camps include sheep, farm, hunting and other short-term camps that functioned as satellites of the habitation or seasonal camp. Special use components include a variety of features such as rock art, roads, and storage rooms that did not involve an over-night stay. Readers should refer to Chapter 6 for more detailed descriptions of the various site types.

¶ 44 Table 7.10 presents the distribution of site types with artifact assemblages over time. The frequency of habitation assemblages (see habitation subtotal row percentages) is fairly evenly distributed over the three major time periods, 1700-1863, 1868-1930 and 1930-1980, although the largest number of habitation artifact assemblages (both single and multiple habitations) date to the 1868-1930 period.

Table 7.10. Artifact assemblages by site type and time period for all components with historic artifacts.

¶ 45 Assemblages associated with temporary camps include a substantial number of unknown (i.e., undated) assemblages, as well as two early hearth assemblages (1600-1700) on Chacra Mesa. Unlike those at habitations, artifact assemblages in the temporary camp grouping increase over time (camp subtotal row percentages). A similar trend is apparent for assemblages at the special use components. Here a substantial number of assemblages are also undated, but as time progresses there are increasing numbers of rock art, sweat lodge, woodcutting, and stone feature components with artifacts.

¶ 46 A somewhat different perspective, but one which nonetheless affirms these trends, is gained by examining the relative proportion of habitations, temporary camps, and special use components to each other in each period. During the 1700-1863 period, habitations are dominant (48 percent), while temporary camps (31 percent) and special use (21 percent) components are less frequent (Table 7.10, column subtotals). By the 1930-1980 period, however, habitations account for only 28 percent of the components while temporary camps (35 percent) and special use (37 percent) components are much more common. In sum, as historic occupation of the survey areas evolved, seasonal habitation declined, as temporary camps and special use components increased.

Artifacts by Time Period

¶ 47 As was seen earlier, historic artifact assemblages at Navajo and other historic components changed substantially in composition between the 17th and the 20th centuries. In order to examine these changes further, the artifacts of each time period will be examined in greater detail. In order to do this we will rely in part, but not completely, on a subset of the data consisting of those artifacts found on components that were occupied during a single time period. Since there are only two components in the 1600-1700 time group, they are combined with the 1700-1863 components in this and some subsequent analyses.

1600-1863

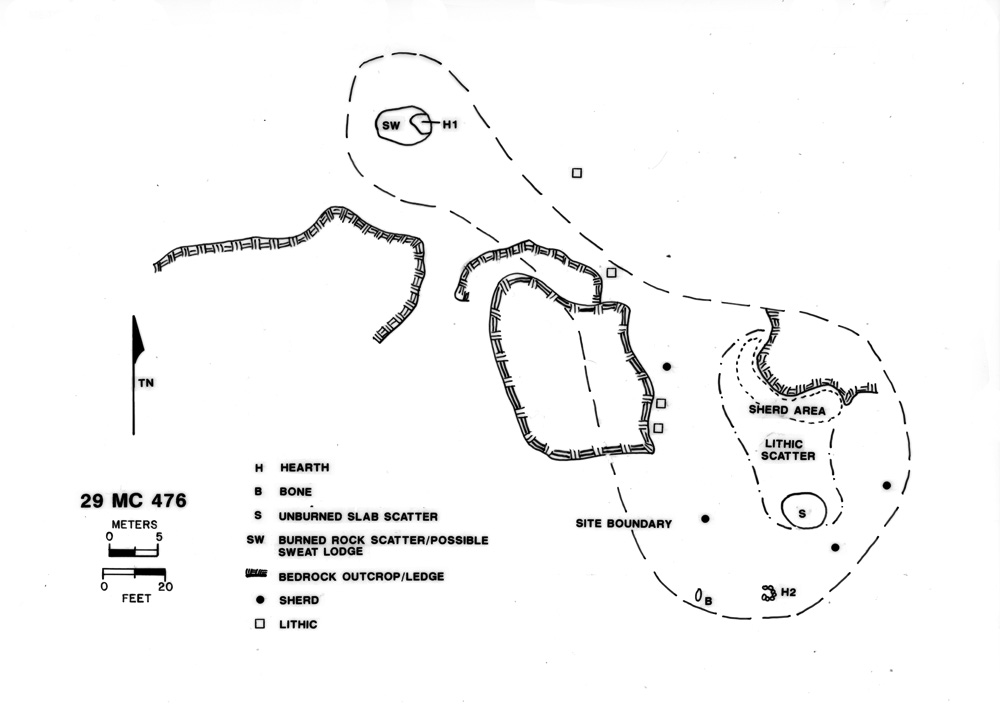

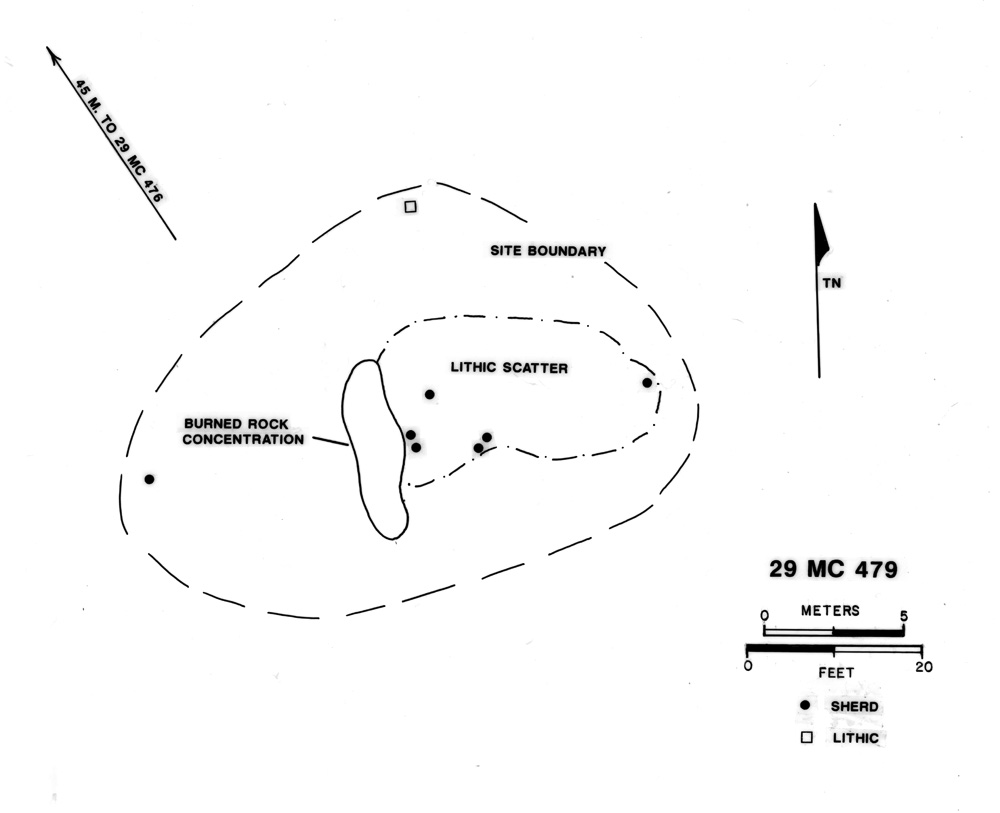

¶ 48 Two early assemblages were found at campsites 29Mc 476 and 29Mc 479 located on the upper, northeast facing slope of the Chacra Mesa addition. The primary features of the two components were scatters of burned and unburned slabs, suggesting hearths, although it is possible they had more permanent structures of which no surface traces remain (Figures 7.2 and 7.3). The two components are within meters of each other and appear to be related. Pottery at the components includes Puname series red ware, Hawikuh Polychrome and Dinetah Gray sherds. Dating of the camps is based on the presence of Hawikuh Polychrome, which was produced between 1600 and 1700 by Zuni Pueblo potters (Harlow 1973). Both camps also have a variety of flakes, debitage, and tools including utilized/retouched flakes, projectile points, a hammerstone and a drill (see Appendix 7.3).

|

Figure 7.2. Plan view of early Navajo campsite 29Mc 476. Hearth 1 may have been the rock heating pit for a sweat lodge. |

|

Figure 7.3. Plan view of early Navajo campsite 29Mc 479. |

¶ 49 Fifty-eight components with artifact assemblages were occupied between 1700-1863 (Table 7.9). Eighteen off these 1700-1863 components also had Euro-American artifacts, although in every instance the Euro-American produced items appear to reflect either artifacts deposited by the component’s inhabitants during later, post-Bosque Redondo periods, or scattered debris from nearby sites of later date. The only possible pre-1868 artifact of non-Native material, a long and narrow metal projectile point, was found on a prehistoric site (29SJ2856) of unknown cultural affiliation (See Appendix 7.2).

¶ 50 Despite the virtual absence of European artifacts and materials, trade by Chaco Navajos for Spanish and Mexican produced items can probably be assumed, although as Brugge (1981b:94) emphasizes, the quantity of items so derived was probably very small, making their discovery in a surface survey unlikely. Brugge (1981b:94) reports that no pre-Bosque Redondo European derived items were present in the collections from Hayes’s (1981) inventory survey of Chaco Canyon National Monument. During his subsequent Tsegai survey, Brugge found no European items predating 1868 (1986:66), and later excavation of the Doll House Site, a 18th and 19th century hogan site immediately north of the Chacra Mesa survey area, produced only a single link of chain of possible 18th century date (Brugge 1986:128).

¶ 51 As such, ceramics, lithics, a few pieces of burned and unburned bone visible in ash heaps, along with an occasional Anasazi sherd, compose the artifact assemblages of the pre-Bosque Redondo Additions survey components. As shown in Table 7. 11, 41 of the 58 components dated to this time period are single period components. The great majority of artifacts found on these 41 components are Navajo and historic Pueblo trade ceramics (70 percent), although lithics account for about 28 percent of the cumulative assemblage (Table 7.12). Bone (both burned and unburned) and Anasazi ceramics were also found, but combined they account for only slightly more than 1 percent of the 1600-1863 period assemblage.

Table 7.11. Frequency of Navajo and historic components with artifacts by time period.

|

Table 7.12. Historic artifact types by time period (single period components only). |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artifact Type | 1600-1863 | 1868-1930 | 1930-1980 | Total | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Historic Ceramics | 1,576 | 70.5 | 286 | 41.9 | 33 | 6.2 | 1,895 | 54.9 |

| Lithics | 632 | 28.3 | 25 | 3.7 | 657 | 19 | ||

| Other artifacts | 9 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.6 | 8 | 1.58 | 21 | 0.6 |

| Anasazi Ceramics | 17 | 0.8 | 13 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.6 | 33 | 1 |

| Euro-American artifacts | 355 | 52 | 492 | 91.8 | 847 | 24.5 | ||

| Total | 2,234 | 100 | 683 | 100.1 | 536 | 100.1 | 3,453 | 100 |

¶ 52 Of the ceramics found at 1700-1863 components, Dinetah Gray is dominant (unidentified plain sherds may also be Dinetah), with plainware accounting for nearly 90 percent of the ceramic assemblage (Table 7.13). As Brugge notes, an initial date for Dinetah in Chaco is uncertain. Despite the two campsites pre-dating 1700, production of Dinetah probably does not pre-date permanent Navajo settlement which likely began sometime in the early 18th century. The earliest cluster of tree-ring cutting dates marking Navajo construction in the Chaco region is a group of dates in the 1720s (Brugge 1978:48). Dinetah seems to have remained in use until the late 1700s or early 1800s (Brugge 1981b:86), although as will be seen in the following pages some Dinetah was found on components post-dating 1868. While they may have been present, the Additions Survey crews did not attempt to distinguish the Dinetah micaceous and transitional varieties described by Brugge (1981b:87).

Table 7.13. Navajo and historic Pueblo ceramic types by time period (single period components only).

¶ 53 Conspicuous for its absence at pre-Bosque Redondo components is Navajo Gray, a successor of Dinetah that first appears around 1800. Navajo Gray is distinguished by its thicker walls, fine sherd temper, fillet decoration and smaller vessel sizes. Brugge (1981b:87) found it in the collections of “51 of the [Chaco Canyon National Monument survey] sites, making it the most common type on historic sites.” It is difficult to account for the absence of Navajo Gray, unless the Additions survey areas were only sparsely occupied during the period of intense warfare between 1818 and 1863. Both Brugge (1981b:98, 101; 1986:25) and Kelley (1982:30) have argued that Chaco was largely abandoned during this interval due to persistent hostilities between the Navajo and successive Spanish, Mexican, and American governments.

¶ 54 The remainder of the 1700-1863 ceramic assemblage is composed of Navajo painted wares and historic Pueblo trade wares (Table 7.13). The former include Gobernador Polychrome and Navajo Painted. Gobernador Polychrome was found in both bowl and jar forms at seven components (although jars accounted for only seven sherds). Brugge suggests that Gobernador Polychrome was never produced in the Chaco area, being procured instead through trade with the Dinetah area, but in light of more recent arguments (see Reed and Reed 1996) contending that this type was produced by Navajo potters prior to the Pueblo Revolt, it seems likely that some production occurred in Chaco, although its scarcity here suggests that a few potters could have easily produced all the vessels found in the Chaco area. Brugge (1981b:87) states that the type ceased to be produced shortly after 1750, a terminus date which seems consistent with the Additions survey results.

¶ 55 Navajo Painted was found at six components, always as bowls. Although all six components where it was found were initially occupied in the 1700-1863 period, two of them were also occupied in subsequent periods. Brugge (1981b:87) dates production of Navajo Painted after 1750.

¶ 56 Historic Puebloan trade wares account for the remaining 7 percent of the pottery found on pre-Bosque Redondo period components (Table 7.13). Although the sample is very small, the tradewares appear to be dominated by pottery produced at Zuni and Hopi. Of 127 sherds of Pueblo plain, red or painted wares, 95 sherds, including Hawikuh Polychrome (as previously discussed), Kiapkwa Polychrome, unidentified Zuni polychrome, Zuni Buff Ware and unidentified Hopi polychrome were found at five components. In contrast, 24 sherds of Puname series red ware and Zia Polychrome, produced at the Rio Grande pueblos of Zia and Santa Ana, were found at two components. Eight unidentified Puebloan sherds make up the remainder. Excluding the red ware and buff ware sherds, bowls account for 54 percent of Puebloan trade ware inventory, while jars compose 45 percent. Adding a bit of diversity is a single unidentified Pueblo polychrome sherd from a Spanish-style soup plate, found at 29SJ 2606, a large defensive multiple habitation dating to the last quarter of the 18th century (see Gleichman, Chapter 6).

¶ 57 Although the sample is small, the range of Puebloan types represented at the pre-Bosque Redondo components is partially consistent with that reported by Brugge (1981b:88-90) for the Chaco Canyon National Monument survey. There, Brugge found very few Tewa or northeast Keres sherds, and a relatively small number of Puname series types, while Ashiwi series polychromes (from Zuni and Acoma) were most frequent. One noteworthy difference between the two surveys is the presence of 18 unidentified Hopi polychrome sherds from four Chaco Additions survey components (Table 7.3). No Hopi pottery was found during the Monument survey. For the Monument survey, Brugge (1981b:88-90) argued that trade with both the Keres and Zuni likely began around 1760 and continued up through 1850, after which it tapered off, as reflected by the absence of later types like Zia Polychrome (1850-present) and Zuni Polychrome (1850-1920). While the presence of Kiapkwa Polychrome at Additions survey components on Chacra Mesa certainly indicates late 18th and early 19th century trade with Zuni, a more detailed chronological picture is difficult to obtain due to the small numbers of sherds and the small number of type-specific identifications. Nonetheless, as emphasized by Brugge, trade seems to have occurred most frequently (at least as viewed from the perspective of pottery) with Pueblo partners who were under only nominal control of the Spanish. Zuni may have offered an ideal situation, “wherein the balance of Euro-American [i.e., Spanish or Mexican] goods and lessened official regulation was readily recognized by the Navajos as providing the safest and most advantageous market, especially in time of actual or threatened war” (Brugge 1981b:90). Navajo and Spanish relations were increasingly shaded by warfare and raiding from the second decade of the 19th century onward.

¶ 58 The lithic assemblage associated with pre-Bosque Redondo Navajo components shows that a substantial range of chipped and ground stone items were in use (Table 7.14). While some of the artifacts found on 1600-1863 components are likely items recycled from prehistoric sites, their presence reflects the daily use of stone materials by Navajos for a wide range of tasks including tool making, hunting, and food preparation. It should be emphasized that the stone artifacts listed in both Tables 7.4 and 7.14 include only those items that were clearly associated with Navajo components or features. Stone artifacts found at sites with mixed Navajo and prehistoric components have been excluded. Because of this the total number of stone artifacts included in the tables is probably substantially smaller than the number of artifacts actually manufactured or used by Navajo inhabitants.

|

Table 7.14. Navajo and historic lithic materials by time period (single period components only). |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithic Type | 1600-1863 | 1868-1930 | Total | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Debitage | ||||||

| Primary Flake | 21 | 3.3 | 1 | 4 | 22 | 3.3 |

| Secondary Flake/Flake Fragment | 192 | 30.3 | 11 | 44 | 203 | 30.9 |

| Angular Debris | 266 | 42.1 | 8 | 32 | 274 | 41.7 |

| Biface Thinning Flake | 24 | 3.8 | 24 | 3.6 | ||

| Sub-total | 503 | 79.6 | 20 | 80 | 523 | 79.6 |

| Chipped Stone Tools | ||||||

| Utilized/Retouched Flakes | 66 | 10.4 | 1 | 4 | 67 | 10.2 |

| Projectile Points | 15 | 2.4 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 2.4 |

| Bifaces | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Drills | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Cores | 13 | 2.1 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 2.3 |

| Hammerstones | 12 | 1.9 | 12 | 1.8 | ||

| Sub-total | 108 | 17.1 | 4 | 16 | 112 | 17 |

| Other Stone | ||||||

| Miscellaneous Shaped Stone | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.9 | ||

| Polishing Stone | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Stone Axe | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.3 |

| Raw Material | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Sub-total | 9 | 1.4 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1.6 |

| Groundstone | ||||||

| One-hand Mano | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 | ||

| Two-hand Mano | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Mano, Type Unknown | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Mano (Large) | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Metate, Type Unknown | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 | ||

| Sub-total | 7 | 1.1 | 7 | 1.1 | ||

| Minerals | 5 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.8 | ||

| Total | 632 | 100 | 25 | 100 | 657 | 100.1 |

1868-1930

¶ 59 Eighty-five historic components have assemblages dated to the 1868-1930 time period, which begins with the return of the Navajo after five years of internment at Bosque Redondo (Table 7.9). As can be seen from the table only nine of the artifact assemblages from this period contained only Native artifacts; the remaining 76 components had items of Euro-American manufacture.

¶ 60 Of the 85 components, 40 are dated to this period only (Table 7.11). The proportions of artifact types at these assemblages are much changed from the preceding, pre-Bosque Redondo period. The frequency of historic Navajo or Puebloan trade ceramics has dropped by nearly 30 percent, while the proportion of lithic items has also declined (by 25 percent). Balancing these reductions is the appearance and increasing frequency of Euro-American manufactured artifacts.

¶ 61 Among the much reduced Navajo and historic Puebloan trade ceramics, Navajo plain wares are still dominant (67 percent), but account for a smaller proportion of the overall ceramic collection (Table 7.13). Dinetah Gray still accounts for the bulk of the plain ware, although its successor, Navajo Gray, was found on one component. Brugge (1981b:87) notes that Navajo Gray was rare by the late 19th century.

¶ 62 Navajo Painted is absent in the 1868-1930 ceramic assemblage, but a variety of historic Puebloan polychromes are present, and although they occur in very small frequencies, they make up a larger proportion of the ceramic assemblage than they did in the preceding, pre-Bosque Redondo period. Of the sherds which can be identified to type, all are from the Rio Grande Keres pueblos; sherds of Zuni or Hopi origin are absent. Although caution is due in view of the small sample, this apparent shift in trading partners may be a product of the cessation of warfare and raiding after the Navajo return from Bosque Redondo.

¶ 63 As Brugge (1986:64) points out in describing the results of his Tsegai survey, “the reduction in ceramic collections from sites post-dating1800 is quite evident.” He attributes this to a lessening use of pottery and to different pottery disposal practices. Beginning in the late 1700s, pottery as well as many other items of material culture were no longer deposited in ash heaps, but instead were taken away from the habitation and deposited in unobtrusive locations in accordance with the proscriptions of Blessingway (Brugge 1981a:15; 1986:93,140, 156 ) . While this may account for some of the isolated Navajo “pot drops” found by the survey, it is nonetheless clear that the role of pottery in Navajo culture was much diminished after 1868.

¶ 64 Much the same may be said for lithic and ground stone artifacts. As shown in Table 7.14, the number of stone items attributable to the 1868-1930 period is less than two dozen flakes and a handful of tools. Projectile points, cores, hammerstones, and manos, frequent in the preceding period, are now rare or absent. Brugge documents similar results for his Tsegai survey, which produced few stone artifacts from post-1868 contexts (Brugge 1986:74-75).

¶ 65 While use of pottery and stone implements dwindled, mass-produced Euro-American goods became increasingly available and widespread during the two final decades of the 19th century. Although Euro-American goods could be obtained at the Indian Service trading post at Ft. Defiance and through itinerant traders and bootleggers well before the first trading posts were established in the Chaco area in the 1880s and 1890s, there are no Euro-American items among the nearly 2,800 recorded by the Additions survey that clearly pre-date 1880.

¶ 66 Frank McNitt (1962:339-340) reports that the earliest trading post in the Chaco area, Tiz-na-tzin, may have been established as early as 1878, and it was certainly in operation a few years later. Located between Tsaya and Bisti, it was approximately 32 km (20 mi) northwest of Pueblo Bonito and over 40 km (25 mi) from the Chacra Mesa sites where most of the survey’s Euro-American artifacts were found. Another store, advertised by an 1887 cliff-face inscription near Pueblo Bonito was described as being “10 miles down canyon,” a location Brugge (1981b:94) suggests may be the same spot later occupied by Tsaya Trading Post.

¶ 67 In the fall of 1897 Richard Wetherill established the Pueblo Bonito Trading Post along the back wall of the ruin, making mass produced goods readily available to the Chaco Navajo for the first time. The initial inventory at the store was described as including dry goods, harness, galvanized ironware and rope, boxed, bagged or canned food supplies, axes, chains, lamps and fuel oil, in addition to candy (McNitt [1957] 1966:173). In The Indian Traders McNitt (1962:79) explains that:

Flour, coffee, and sugar — in that order — were the staples most in demand and therefore most in supply at the old trading posts. Tobacco, by the plug or can, was greatly desired but considered more of a luxury than were yards of bright flannel, velveteen, or calico. Canned goods — fruits and vegetables — stocked the shelves from the early eighties, but the variety was limited and not too well regarded by the Indians for twenty or thirty years more.

¶ 68 Brugge (1980:161) reports that in May of 1898 Wetherill had several Navajos construct a new building to house the Pueblo Bonito Trading Post. In a letter to Talbot Hyde, one of his Hyde Exploring Expedition partners, Wetherill states that the trade has “been 20 to 60 dollars per day,” and that “We buy everything offered of marketable value — Sheep, Goats, Mules, wool — Pelts etc. — All the blankets in the region come to us.” The Hyde Exploring Expedition quickly added more stores in the following years. In 1901 a Farmington newspaper reported that the Expedition was operating seven stores in addition to the Pueblo Bonito post. The nearest of these was identified as the “Escavada” store, probably located near Kimbeto. The Hyde Exploring Expedition trading empire proved to be short lived, but the Pueblo Bonito store remained open under Richard Wetherill’s ownership for over a decade, and with the apparent exception of intervals between owners or managers, the store remained in operation until 1949 (Roberts n.d).

¶ 69 A variety of Euro-American artifacts found on survey components, including brown, aqua, and purple bottle glass6Purple and amber glass are the product of the reaction of natural glass (usually light green to light brown in color) to the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Over time, originally clear natural glass turns various shades of purple, amber or a milky translucent white. Natural glass not exposed to the sun, as in glass bottles that are buried or otherwise shielded from the sun, maintains its original color. Glass that did not change color was not manufactured until the 1920s and 1930s. See Duran and McKeown (1980: 1039-1040) for a more detailed discussion., Mentholatum and cold cream jars, steel meat cans, enamel ware, tobacco tins, baking powder cans, and bleach bottles7Bleach, according to Duran and McKeown (1980: 1082) was used by Navajos to purify drinking water. Kelley (1982: Table 29, 334) reports that it was used by Sargent’s Spanish-American herders for laundry, and was apparently rare on Navajo sites in the Gallo Wash Mine Lease. Bleach bottles were found on three Chaco Additions sites, 29SJ 2451, 29SJ 2699 and 29SJ 2966. were probably obtained from either the Pueblo Bonito store or others established around Chaco Canyon after the turn of the century. While some of these containers and goods, including glass, stoneware, evaporated milk cans, sardine cans, and enamel ware were produced long before the opening of the Pueblo Bonito store, local Navajos would have had difficulty obtaining them. As such, it seems likely that most Euro-American items found on the survey components post-date the opening of trading posts in the Chaco Canyon area around the turn of the century.

¶ 70 Although nearly 2,800 Euro-American artifacts were identified by the survey, only 847, or about 30 percent of the items were associated with single time period assemblages dated to either the 1868-1930 or 1930-1980 periods (Table 7.15). Glass containers dating prior to 1930 are primarily bottles and jars probably originally containing beer, liquor, or soda pop. Distinctively shaped or colored small jars held Mentholatum, Vicks Vapo-rub or cold cream. Cans contained vegetables, fruit, meat, liquids, evaporated milk, coffee, baking powder, sardines, and lard, as well as tobacco, although with the exception of distinctively shaped cans used for meat, coffee, lard, sardines or tobacco, it was usually impossible to identify the contents since labels were not preserved after decades of exposure.

Table 7.15. Euro-American manufactured materials at Navajo and historic components by time period (single period components only).

¶ 71 Cooking and food preparation implements included earthenware, porcelain, enamelware and utensils. Although relatively few enamelware cooking, serving pieces or washbasins could be isolated to the 1868-1930 period they were common and were found on components of this period as well as the succeeding 1930-1980 interval. Similarly, cooking stoves and kerosene lanterns were widely used during both periods, although they do not appear in any 1868-1930 single period assemblages.

¶ 72 Whetstones, shovels, and buckets were common tools, while hardware included nails, screws, pieces of galvanized pipe and a bewildering variety of unidentified metal, much of it probably associated with wagons, harnesses or stoves. Bits of harness, a cowbell, a saddlehorn, and sheep rattles (recycled cans with crimped ends containing pebbles used in herding sheep; see Duran and McKeown 1980:1090) provide glimpses of the importance of animal husbandry. In addition to these items, two medicinal products, Vicks Vapo-rub and Mentholatum were found on ten Chaco Additions components. Although they may have been purchased to ease human complaints, they also have a history of use for doctoring sheep8In order to trick reluctant ewes into allowing their own lamb or an orphan lamb to nurse, Spaulding and Clay (2010:161) suggest rubbing Vicks Vapo-rub on the ewe’s nose and the lamb’s body to deaden the ewe’s sense of smell and the lamb’s scent. Two turn of the 20th century veterinary guides note the use of Mentholatum for “big head” (Smith 1918) and “nasal catarrh” (Baker 1920) in sheep.. As discussed by W. Powers in Chapter 8, sheep and goat husbandry were the basis of Navajo subsistence and cash economy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a fact that is easily ignored in view of the sparse material record.

¶ 73 A variety of gun cartridges were found on components of the 1868-1930 period and since it seems unlikely that shell casings would have been brought back from hunting forays, their presence may indicate an occasional serendipitous shot at an unwary rabbit, coyote or bobcat. Guns were not used in the killing of sheep or goats, whose throats were slit so that the blood could be collected for blood sausage or pudding (Downs 1964:47; 59). Although Duran and McKeown (1980:1093), in their analysis of historic artifacts in Block II of the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project, found that some shell casings were cut-up to make jewelry, no cannibalized casings were noted by the Additions survey. Despite the substantial amount of money that was likely spent on clothing9Reh (1983:14-15) states that clothing accounted for a fifth of the goods bought by Navajos from traders in the Kaibito area, a proportion that was somewhat smaller than that for the Navajo Reservation as a whole in 1939. In the Kaibito area clothing was the “second most important category for which Navajo income is spent.”, the only remaining traces of apparel found on pre-1930 components were shell and glass buttons. Although cloth exposed to weather soon decomposes, Reh (1983:15) reports that in the Kaibito area, old clothes were burned instead of being reused or discarded (see also Ward et al. 1977:269-270).

1930-1980

¶ 74 A total of 82 components had artifact assemblages dated to the 1930 to 1980 time period (Table 7.9). With the exception of a few components with small quantities of very recent Euro-American artifacts, virtually all of the components dated to this period were abandoned by the early to mid- 1950s. Several factors contributed to the decline, and finally cessation, of settlement within the survey areas. First, intense competition for grazing land between Navajo and Spanish-American and Anglo herders resulted not only in overgrazing, but in compartmentalization of the landscape as land was allotted, purchased, leased and increasingly as time went on, fenced. From the 1910s through the 1920s and 1930s, Navajos had an ever more difficult time finding areas where they could graze their stock (see Chapter 8; also Brugge 1980; Kelley 1982: 49-77 ). Implementation of Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier’s stock reduction program in 1933, forced Navajos to reduce their already diminished herds, hurting small stock raisers disproportionately (Brugge 1980). As if these problems were not sufficient, they were compounded in 1934 by the National Park Service’s decision to begin fencing Chaco Canyon National Monument in order to prevent livestock grazing within the park. Although portions of the Monument were not enclosed until 1947, much of the Monument had been fenced by 1936, and most Navajo residents in order to keeps their herds also left10A few Navajo families continued living in the Monument until the spring of 1948 (Brugge 1980:486). (Brugge 1981b:431, 437-438, 484-485).

¶ 75 Although the Additions survey areas remained unfenced, livestock access to these areas, particularly Chacra Mesa, was increasingly difficult. On Chacra Mesa, the largest and longest occupied site, 29SJ 2966 was abandoned by 1953 or 1954 (see Appendix 8.1). A handful of components have occupation ranges into the 1960s or 1970s (Appendices 7.3 and 7.4), but these either reflect the long production spans of Euro-American artifacts that were discarded in the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s, or disposal of occasional “intrusive” artifacts (like pop-top soda or beer cans) by non-resident visitors in the 1960s and 1970s. The bulk of occupation, and the preponderance of artifact use during this period occurred within the 20 year period from 1930-1950.

¶ 76 As shown in Table 7.10 (column subtotals), habitations of this period account for about 28 percent of the components with artifact assemblages, while temporary camps have 35 percent of the assemblages and special use components 37 percent. It is interesting that the proportion of habitations is significantly lower than in the preceding post-Bosque Redondo period, while the proportion of temporary camps and special use components is substantially higher. Temporary camps and special use components may be more numerous not only because they were more visible to archaeologists (in comparison to sites of previous periods), but probably also because they indicate a shift to a more mobile lifestyle which produced more short-term sites.

¶ 77 Table 7.9 shows that only five components had assemblages of Native artifacts while the majority of components (49 percent) had small mixed assemblages, and a smaller, but substantial proportion (33 percent) had large mixed assemblages. Out of the 82 1930-1980 components, 48 (59 percent) had assemblages dated exclusively to this period (Table 7.11). The types of artifacts found in these single period assemblages (Table 7.12) show that Navajo and historic Puebloan ceramics have declined in frequency to the point of being novelties, while chipped and ground stone are absent altogether. The late occurrence of the Navajo and historic Pueblo pottery types found at 1930-1980 period components suggests that most of these ceramics reflect either heirloom vessels or sherds collected by residents (Table 7.13). Zia Polychrome, found at one component, continued to be produced and may be an exception.

¶ 78 Replacing these Native artifacts, are Euro-American manufactured items (92 percent). Because the majority of Euro-American artifacts were found at components that were occupied during both post-Bosque Redondo periods, it is difficult to identify trends in Euro-American artifacts over time with confidence. Nonetheless, a few general observations are possible. A count of the categories of Euro-American items found at components occupied after 1930 (95 categories of artifacts) shows an increase of about 17 percent when compared to a count of the categories at pre-1930 components (79 in the 1868-1930 period) (Table 7.15). This is partially a reflection of the proliferation of manufactured products available to consumers, but it is also a reflection of an ability and willingness to consume them. Soda pop cans, lotion bottles, medicine jars, glass and china serving dishes, motor oil and anti-freeze cans, tooth powder and tooth paste tubes, steel drums (cut down for use as stoves), flashlights and batteries, air mattresses, paint can openers, staples and nails, wire, automobile tires and tire patching kits, vaccine bottles (presumably for livestock inoculations), watches, eyeglass lenses and dog collars, although not necessarily post-dating 1930, are all signals of the increasing participation of Chaco’s Navajo residents in the American consumer economy.

Artifact Functional Categories

Functional Categories by Site Type

¶ 79 It was anticipated that the various types of components documented by the survey would produce artifact assemblages that reflected their use. Habitation assemblages would consist of a broad range of artifacts reflecting the many domestic activities that occurred at these components. Temporary camps, as short-term camps, would also produce evidence of domestic activities, although the range of artifacts would be less, reflecting their shorter occupancy. Special use components, used for only one or a few activities, would have a much more truncated range of artifacts reflecting those specific uses.

¶ 80 In order to determine if these anticipated assemblages differences were supported by the artifact data, the historic artifact assemblages were sorted into nine general functional categories shown in Table 7.16. Category 1 consists of food, food preparation and storage items and embraces a broad range of disposable food containers, food preparation and serving items, food storage containers and food remains. Category 2 includes clothing, personal hygiene items, medicines, lotions, tobacco and other items of a personal nature. Category 3 contains a wide variety of hardware and domestic maintenance items such nails and screws, wire, tools, lanterns, axes, buckets, milled wood and metal. Category 4 consists of hogan, tent or shelter furnishings such as tables, stools, storage boxes, hangers, and window glass and screens. Category 5 encompasses wagon and car parts, as well as products needed to maintain them. Category 6 includes barbed wire, bridles and harnesses, sheep rattles, troughs, and fence posts related to husbandry of domestic animals. Category 7 is child’s play and is limited to children’s toys. Several doll or play houses constructed of stone and sticks were found by the survey (see Chapter 6) but were classified as features rather than artifacts. Category 8 concerns hunting and is limited to hunting implements such as projectile points and gun cartridges. Category 9 includes a wide range of other or unknown artifacts which either had a variety of potential uses that made pigeon-holing them difficult, or their uses were unknown, or as in items like dog collars and glass insulators, they did not readily fit into the other general categories. Included within this miscellany are Anasazi sherds, pebbles, and fossilized shark’s teeth. Brugge suggests that Anasazi sherds and pebbles may have been collected and brought to sites by children (Brugge 1986:115, 127), and it seems plausible that the shark’s teeth may have arrived at sites in the same way. However, since it was impossible to determine how these items were used, they were placed in the other/unknown category.

Table 7.16. Specific artifact types grouped by general functional artifact categories.

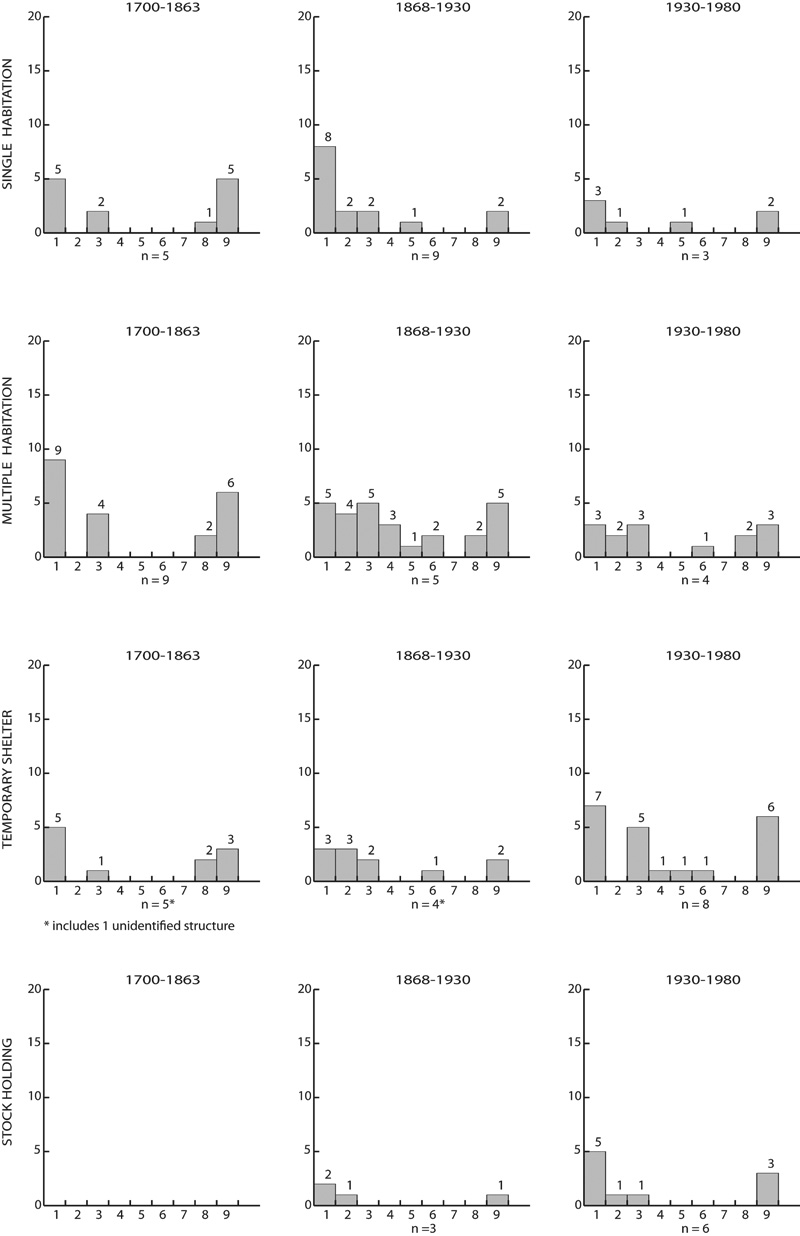

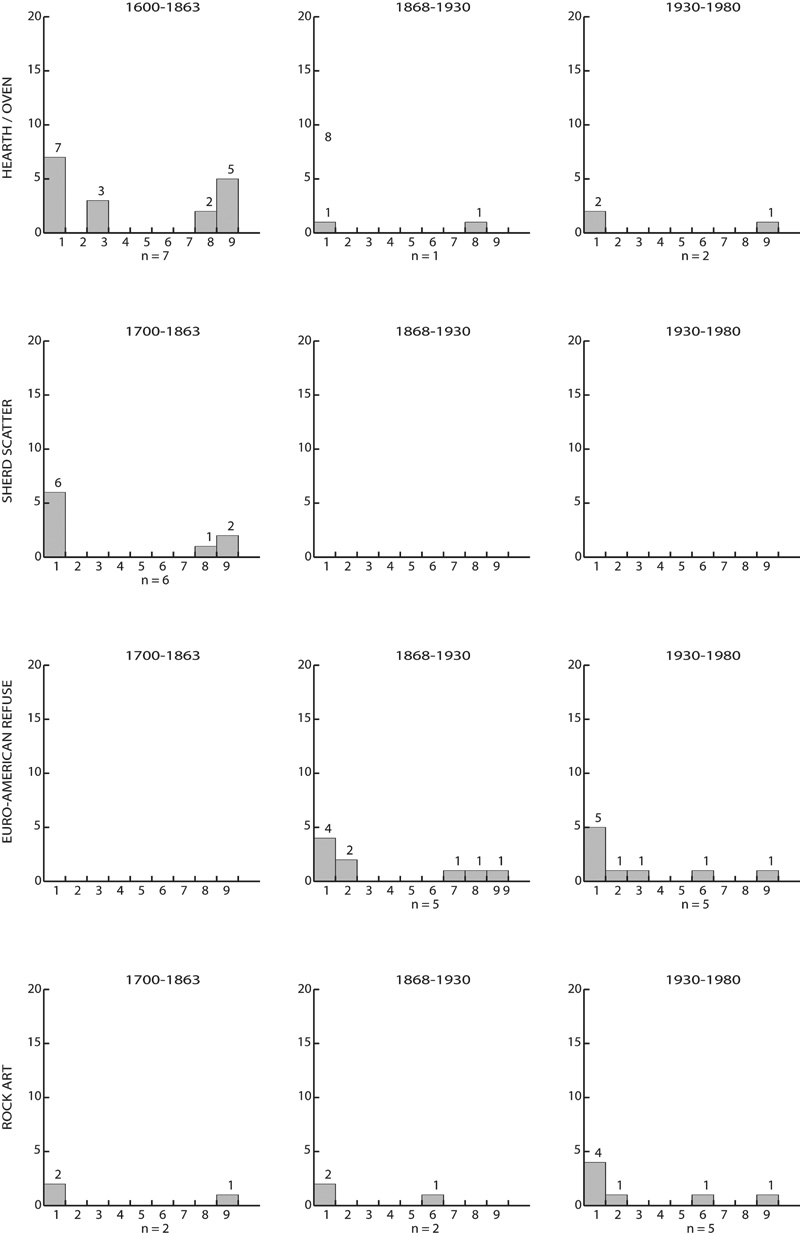

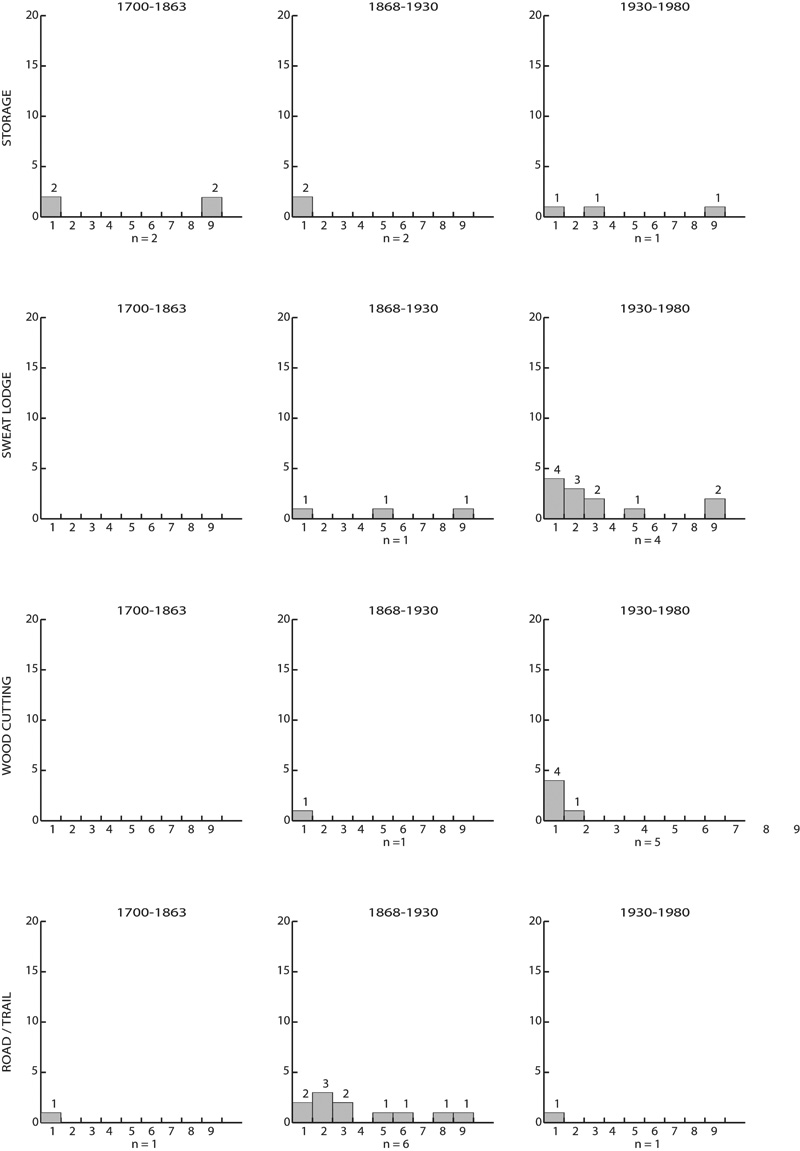

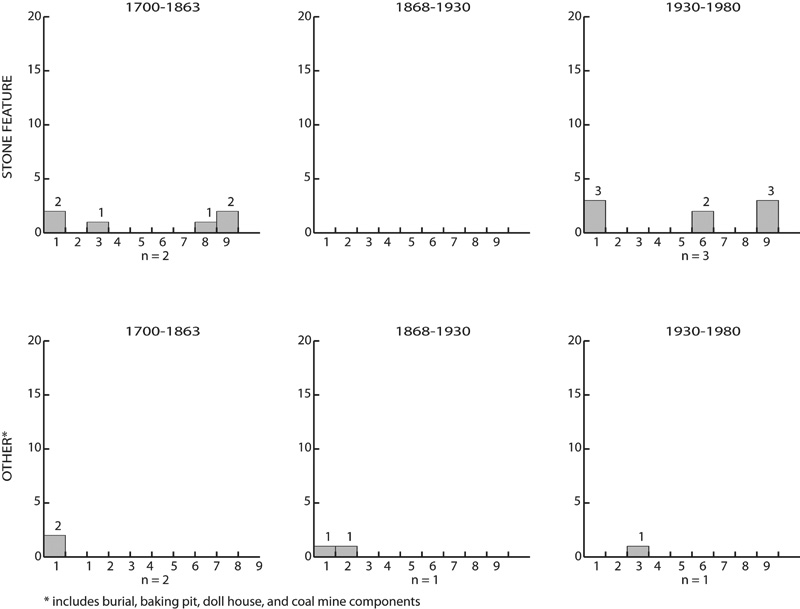

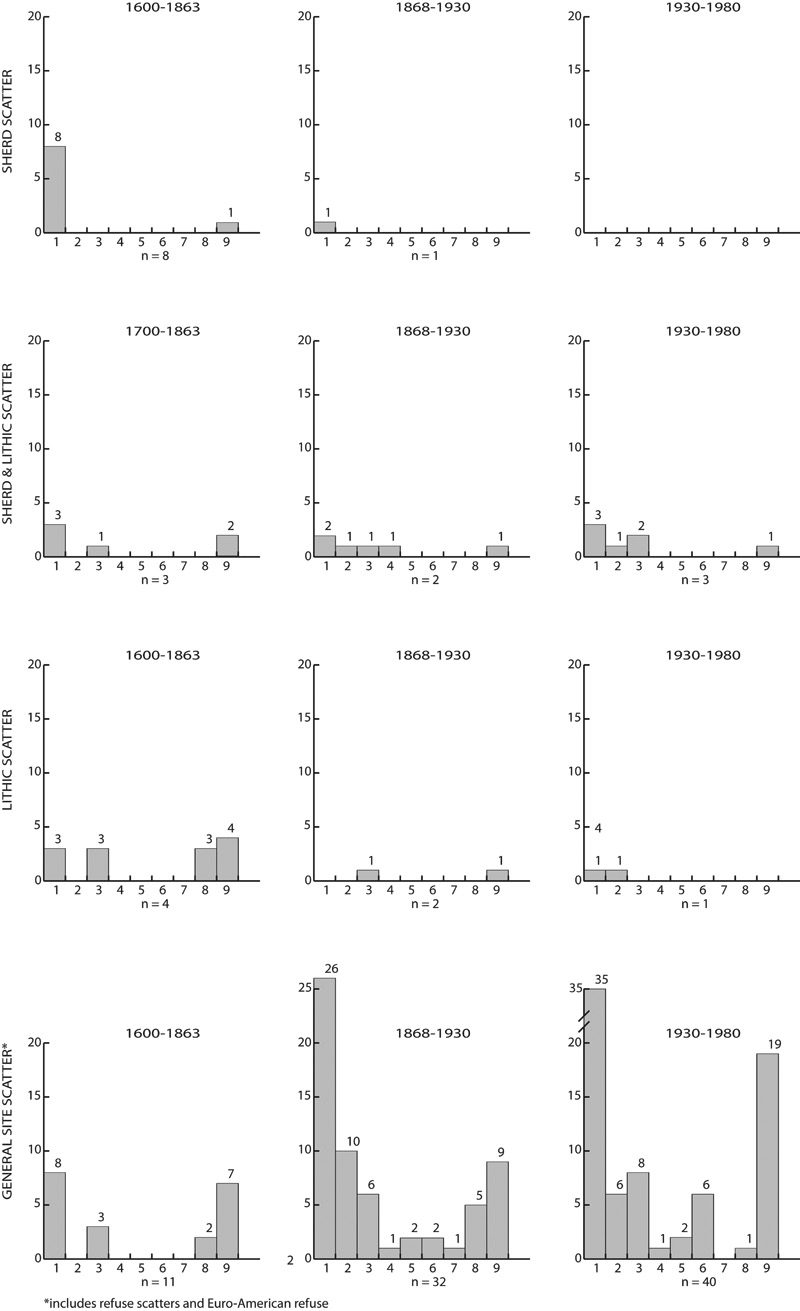

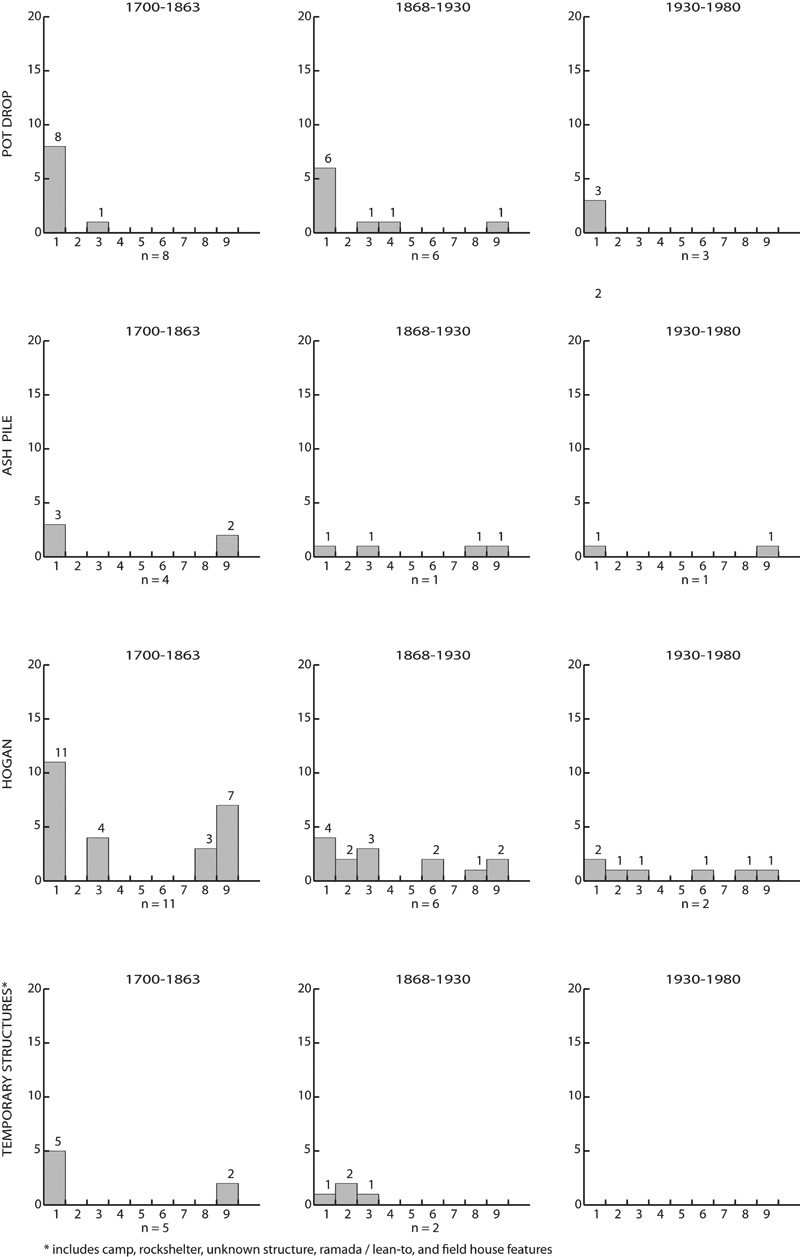

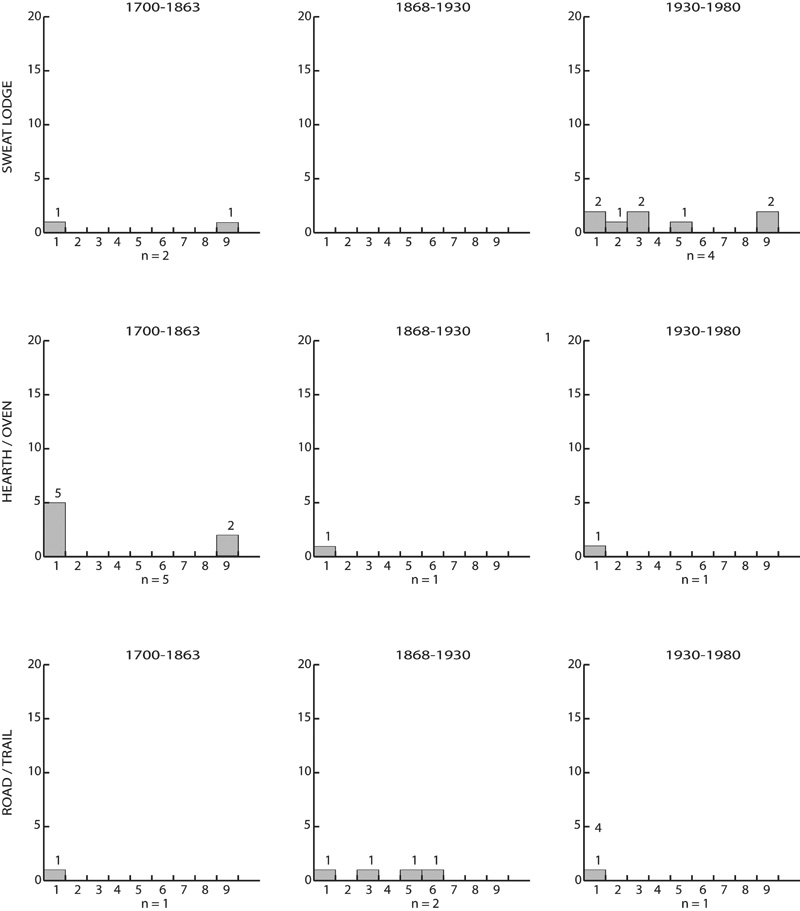

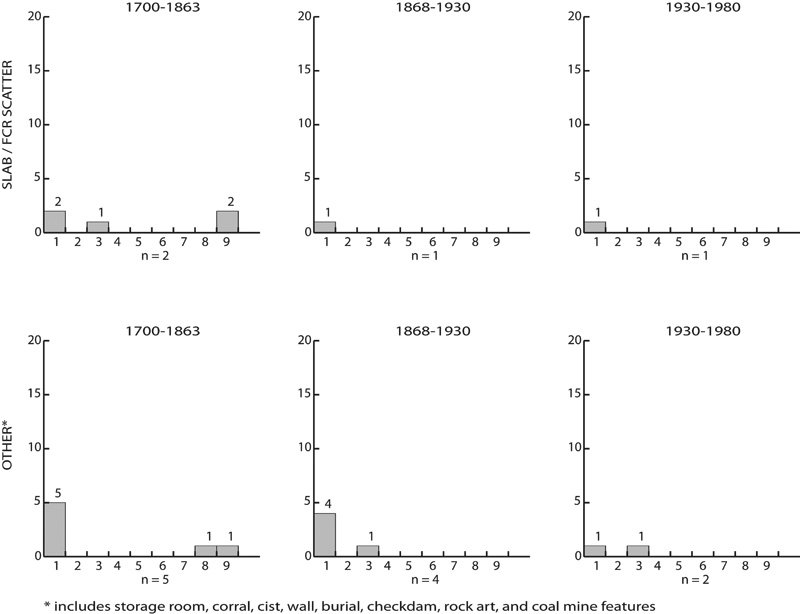

¶ 81 Table 7.17 shows the number of artifact categories present at each site type by time period for all components that could be dated to a single time period. Figure 7.4 presents the same information graphically. In the table, the number of components of a particular type is shown on the left, and under each column heading, the number of components with artifacts of that functional category is indicated. The far right column shows the total number of categories represented by artifacts at a given site type. For example, during the 1600-1700 time period, there are two hearth components. Artifacts from the food, food preparation, and storage (hereafter referred to simply as food preparation), hardware/domestic maintenance (hereafter domestic maintenance), hunting, and other/unknown categories occurred at each of the components. The analysis, as such, is intended to provide a picture of the range of activities that occurred at a given site type, and to show whether these activities change over time.

Table 7.17. Navajo and historic site types by time period with number of general functional categories. Components occupied during two or more time periods are excluded.

|

Figure 7.4. Functional artifact categories by site type for three historic time periods. Number of cases is shown under each graph. |

¶ 82 For the 1700-1863 period, Table 7.17 reveals that every component had food preparation artifacts. The second most common category, other/unknown artifacts, were present at slightly over 60 percent of the components. Smaller proportions of components have domestic maintenance and hunting artifacts. From the perspective of site type, single and multiple habitations, temporary shelters, unidentified structures, hearth/ovens, sherds scatters and stone features have artifacts of up to three or four functional categories, although most individual components of each type have fewer functional categories. For example, all five single habitations had artifacts in the food preparation and other/unknown categories, but only two had domestic maintenance artifacts and only one had hunting artifacts.

¶ 83 Most components with more specialized functions, such as rock art and storage, have one or two functional categories, but there are also only one or two components of each of these types. It is worth noting that artifacts such as Anasazi ceramics, debitage, utilized/retouched flakes, bifaces, flakes, miscellaneous shaped stone, and cores, all present in assemblages of 1600-1700 and 1700-1863 components, were placed in the other/unknown category because it was difficult to determine how or if (particularly in the case of debitage and flakes) these items were used.

¶ 84 During the 1868-1930 period, functional artifact category distributions show more variation both between and within site types, a change which at least in part reflects the addition of Euro-American artifacts to most assemblages. Eighty percent of the components from this period have food preparation artifacts, while 40 percent have personal items, 27 percent domestic maintenance artifacts and another 32 percent have other/unknown items. The drop in representation of other/unknown items is a reflection of the decline in lithic artifacts which made up a large proportion of the items in this category during the preceding 1700-1863 period. All of the remaining functional categories are represented at one or more components, although the frequencies of components with furnishing, transport, animal husbandry, child’s play and hunting artifacts are low. Single and multiple habitations, temporary shelters, Euro-American refuse scatters, and road trail components have totals of from five to eight functional artifact categories, although many of the components making up each type have fewer functional categories. Of the nine single habitations, for example, eight have food preparation artifacts, but only one or two components have artifacts in the remaining four categories. Most of the components with a lower number of artifact categories are again more specialized site types such as rock art, storage, hearth/ovens, woodcutting areas and doll houses.

¶ 85 In the 1930-1980 time period many of the same trends continue. Food preparation artifacts are again present at most components (87 percent), while other/unknown (48 percent), domestic maintenance (29 percent) and personal (21 percent) artifacts are common. Furnishing, transport, animal husbandry and hunting artifacts are present at a few components. Single and multiple habitations, temporary shelters, stockholding facilities, Euro-American refuse, rock art, and sweat lodge components have up to four to eight functional artifact categories, although individually most components have artifacts of only one or two categories. Most special use components have less than three functional artifact categories.

¶ 86 Looking at all of the time periods, it is clear that the range of functional artifact categories becomes more diverse over time from the 1700-1863 period where assemblages are composed exclusively of Native artifacts, to the later post-Bosque Redondo time periods when Euro-American manufactured items become dominant. Much of this reflects the increasing use and variety of Euro-American consumer goods over time.

¶ 87 Habitation components have relatively high total numbers of artifact categories during all three periods, while special use components often, but not always, have fewer functional categories. A variety of site types which functioned as short-term camps including temporary shelters, unidentified structures, stockholding features, hearth/ovens, sherd scatters and Euro-American refuse scatters, have artifact category totals that fluctuate from high to low total numbers of artifact categories from period to period. Some of the specialized site types such as sweat lodges, road/trails, stone features, and rock art also have artifact category totals that fluctuate over time from high to low totals.

¶ 88 Since it was expected that the assemblages of habitations, and to a lesser extent, those of temporary camps, would include artifacts from a broad range of domestic activities, the generally higher totals at habitations and at some temporary camp meet initial expectations. The lesser total numbers of artifact categories found at some special use components are also consistent with our expectations, but what is interesting is the frequent lack of correlation between the inferred function of these components, based on the presumed use of their architectural features, and the artifacts found on them. Storage components, presumably used for storage of food stuffs (and perhaps non-food items as well), did consistently produce food related items, but so did rock art components, where food related artifacts were not foreseen. Perhaps even more unexpected, the nine stockholding components in the post-1868 periods did not yield a single animal husbandry artifact, but produced plenty of food related items and even a few personal artifacts. Since the stockholding components were classified as one of several types of temporary camps, the presence of food and personal items is probably less surprising than one might initially think, but still the total absence of stock raising items was unexpected.

¶ 89 Several conclusions may be drawn from these results. First and foremost, food items, indicated by pottery at early components, and later by disposable cans and glass containers, occur almost everywhere, while personal, domestic maintenance and other/unknown artifacts are present some of the time, and furnishing, transport, animal husbandry, and hunting artifacts are present occasionally or rarely. Second and equally evident is the great range of variability in the number of functional categories between different assemblages of the same site type. Some habitation assemblages have artifacts reflecting a broad range of functional categories, while others have artifacts of only one or two categories. Third, and by no means least, temporary camps and special use components have artifacts that sometimes seem to bear little direct relationship to the architectural features at hand, with stock raising components being a case in point.

¶ 90 In order to better understand these findings, it may help to begin by evaluating two factors that probably did effect the results at some components during some time periods. At pre-1863 components, the small number of functional categories is partially a result of our inability to assign a specific function to many of the chipped stone artifacts. While this has reduced the number of functional categories at components with lithic artifacts, it does not explain the variability in assemblages (the same lithic artifact types were assigned to other/unknown at every component) or the functional disconnect between features and artifacts at late 19th and 20th century components without lithic artifacts.