Previous | Table of Contents | Next

6.

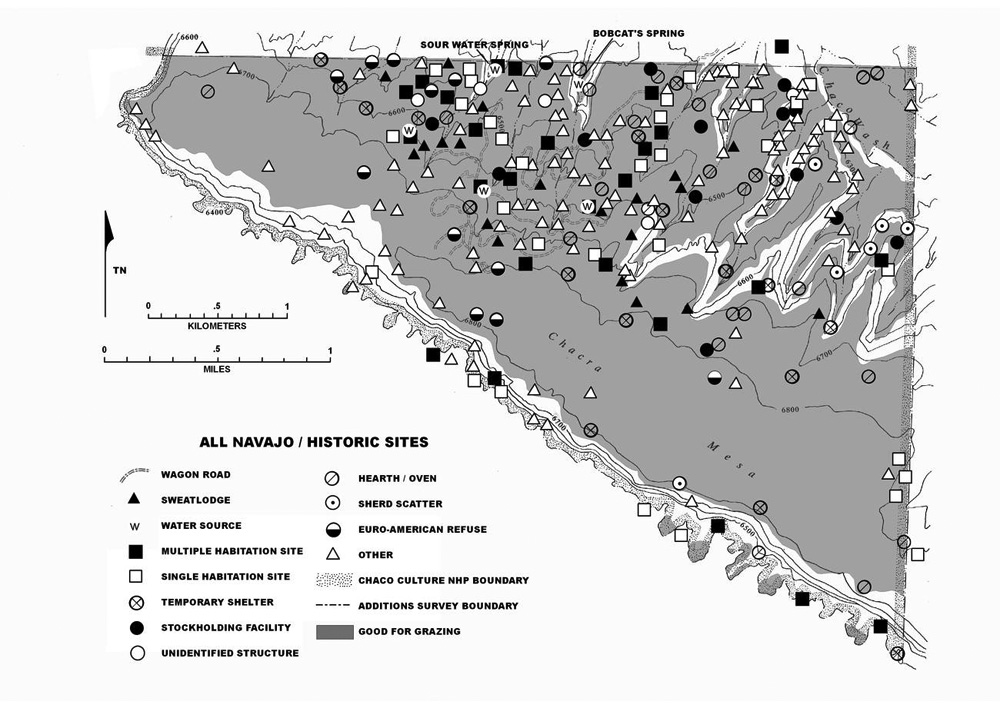

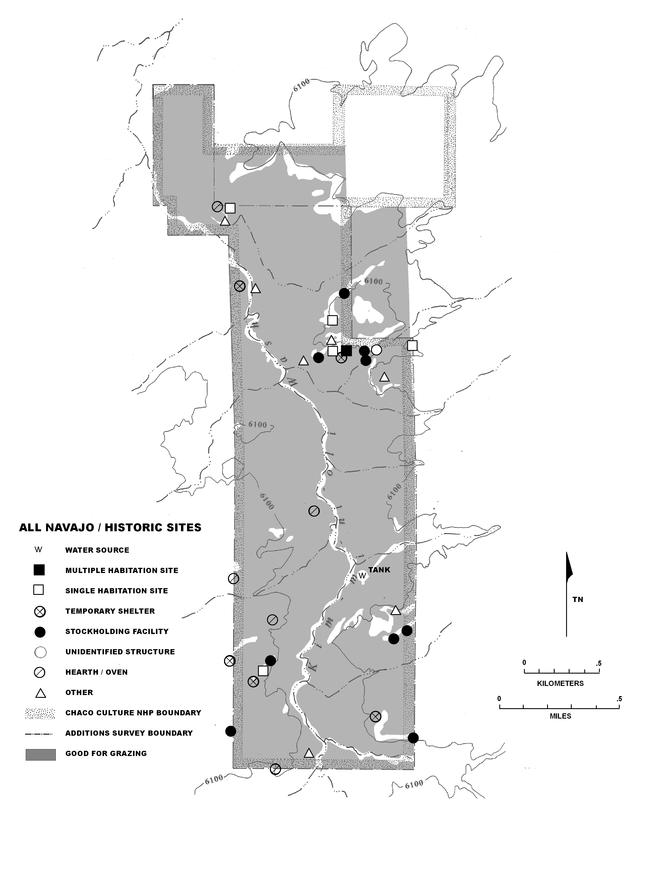

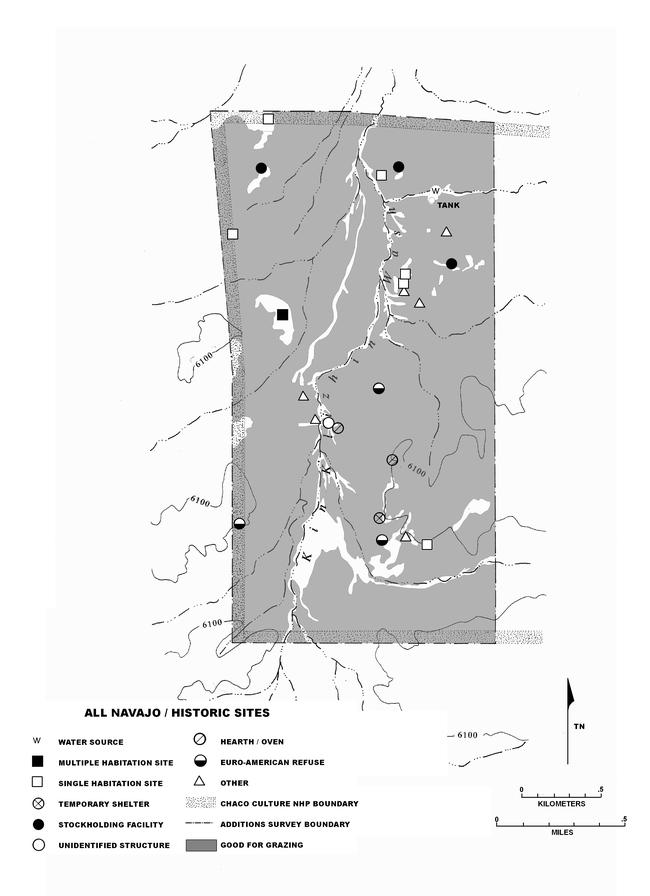

Navajo and Historic Sites and Settlement of the Chaco Additions Inventory Survey

Carol Legard Gleichman

¶ 1 The historic and prehistoric occupations of the Navajo Indians of northwestern New Mexico have received considerable attention in the past decade from both archeologists and ethnohistorians (cf. Gilpin 1983; Wozniak 1983; York 1983). These studies have vastly improved our understanding of changing Navajo lifeways. In the Chaco Region, interpretations of Navajo material culture are found in Brugge’s (1981, 1986) extensive work on the Chaco Canyon Navajos and Vivian’s (1960) master’s thesis on the early Navajo occupation of Chacra Mesa. Klara Kelley’s (1982a) and Garrick and Roberta Bailey’s (1982) substantial ethnohistories provide us with additional understanding of Navajo economy and land use during the historic period. All of these studies together present an excellent framework for the present analysis.

¶ 2 An overriding theme in much that has been written about the Navajo is their great cultural flexibility (Aberle 1963; Bailey and Bailey 1982; Brugge 1986; Winter 1983; York 1983). Regional and local variation in Navajo culture reveals that these people were able to adapt to changing environmental conditions, as well as economic forces and government policies (Bailey and Bailey 1982:586-588; Brugge 1986:i-ii). The Navajo who occupied the Chaco Additions were no exception. The sites recorded were abundant and varied, a fact which made the division of those sites into discrete typological categories a challenging task.

¶ 3 Three hundred and sixty-four sites with Navajo, Spanish-American, Anglo-American or indeterminate historic components were recorded in the Chaco Additions. While all of these sites are historic, the term “historic” is most frequently applied to sites of the historic era that are of indeterminate cultural affiliation. Sites with Euro-american manufactured materials (steel, glass, rubber, plastic, aluminum) of the late 19th and 20th centuries, but without other culturally diagnostic artifacts or architecture, account for a substantial portion of this group of indeterminate sites.

¶ 4 Many of the historic period sites (55 percent) also contain Anasazi and/or Archaic components, revealing a degree of similar attraction to certain areas by these culture groups, as well as reflecting the great site density in the survey areas. Many of the sites are also multicomponent and/or multi-ethnic, with more than one occupation within the historic period; for example, many Navajo temporary campsites and habitations also contain later Navajo rock art panels or Spanish-American inscriptions. The 363 sites have been organized below into a typological framework based on major morphological attributes. Feature summaries of these sites are presented in Appendix 6.1, Table 1. Descriptions of each site type are followed by a test of the typology and a discussion of Navajo settlement patterns and demography. First, however, a brief historic overview of the Chaco Area is presented.

Historic Overview

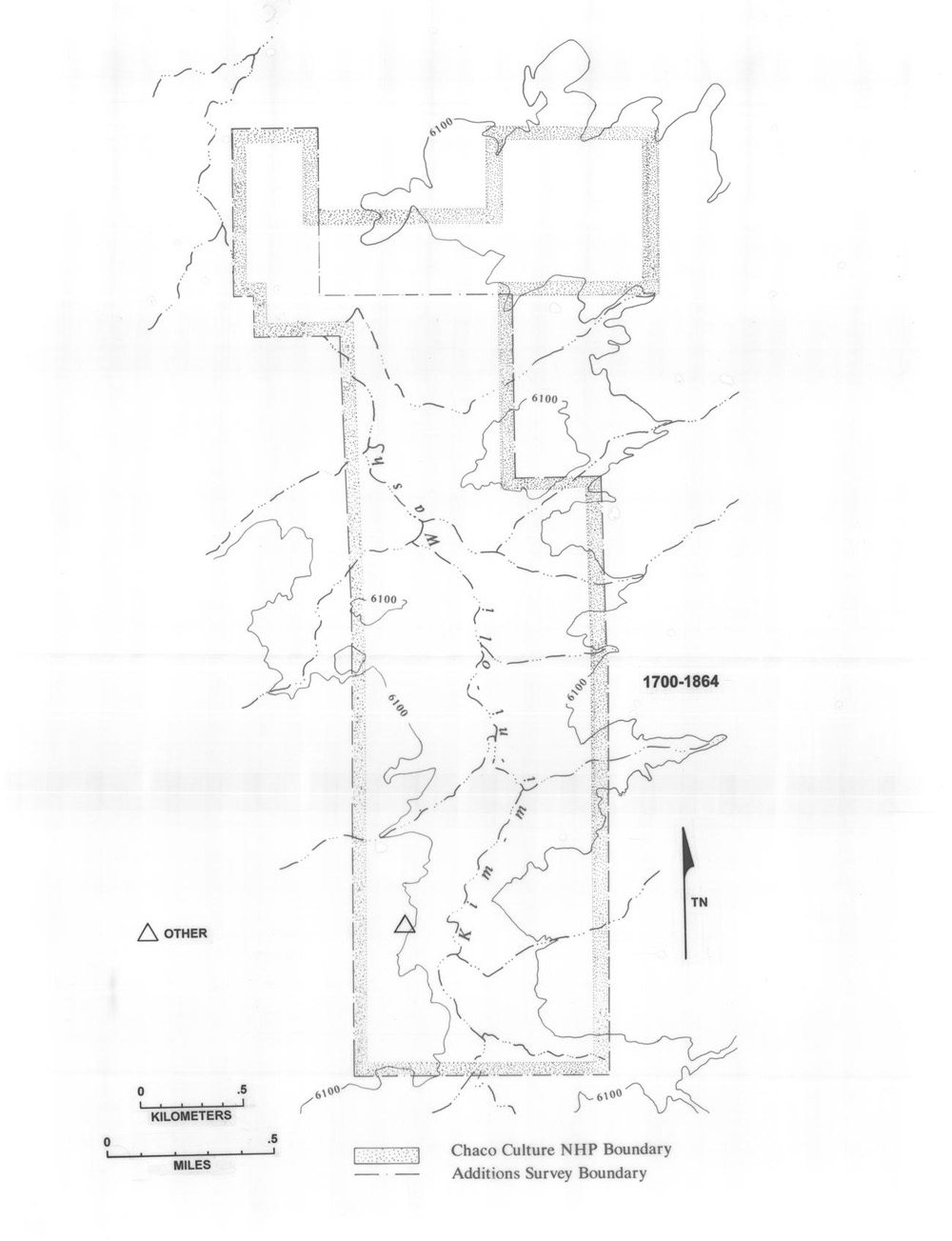

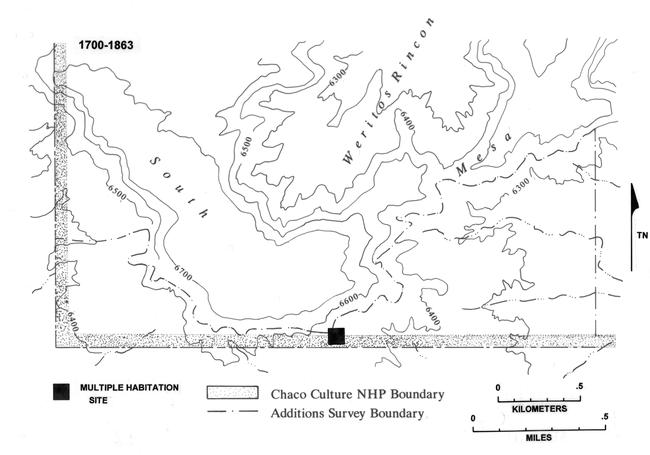

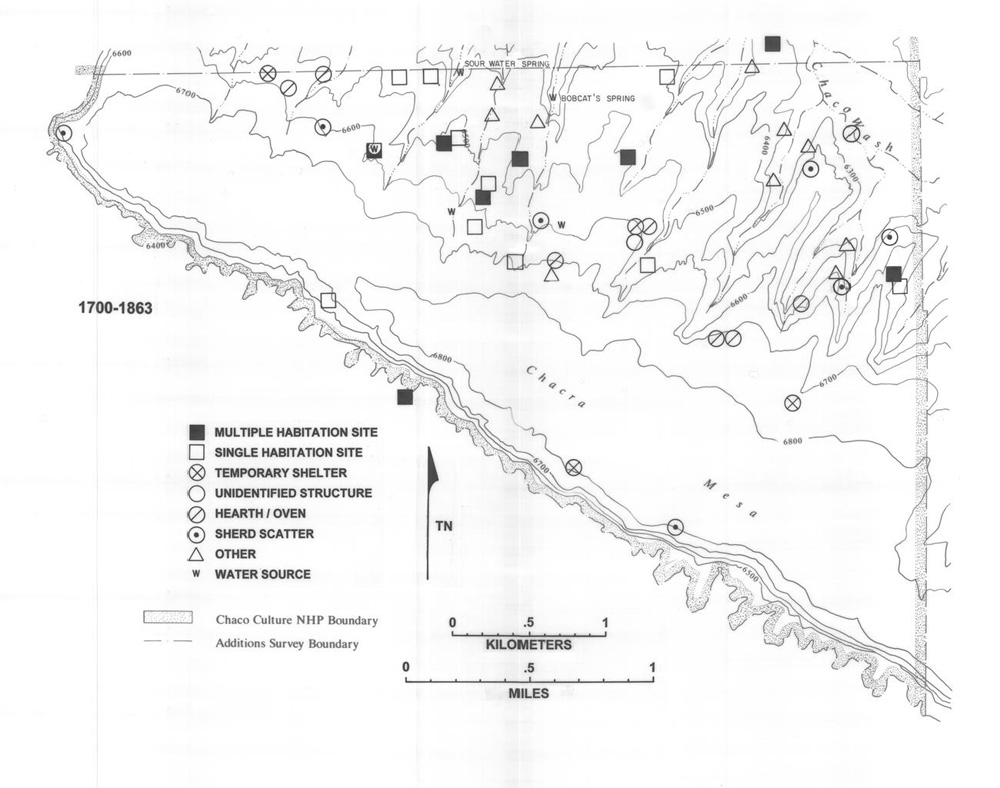

Pre-Bosque Redondo Period: 1700 to 1863

¶ 5 The broad area west of the Rio Grande pueblos and north of Acoma is thought to have been occupied by the 1580s, if not earlier (Brugge 1986:141; Forbes 1960).1Since this chapter was written archaeological investigations in the northern San Juan River Basin have demonstrated the presence of Navajo sites in the Dinetah area by the mid-1500s, with occupation projected back into the 15th century by some researchers (Dykeman 2003: 36-37; Reed et al. 1999). In light of this, it seems likely that the dates for initial Navajo occupation of the Chaco area will be pushed backward in time by future research. Although non-cutting tree-ring dates as early as the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries have been recovered from Navajo sites in the Chaco area, the earliest clustering of tree-ring dates is for the early 1720s (Brugge 1978:48). The clustering of these dates indicates that they are close to cutting dates. The reliability of tree-ring dates earlier than 1720 is questionable, particularly in light of the general absence of other evidence (e.g., ceramics, archeomagnetic dates) supporting occupation prior to the early 1700s.

¶ 6 These early Navajo sites are described as small pueblitos and settlements of hogans which were primarily built in or near the side canyons draining the northeastern flank of Chacra Mesa. They tended to be in areas close to agricultural lands and were often located defensively, to guard against Ute and Comanche raiders (Brugge 1986:142; Vivian 1960:218).

¶ 7 The herding of sheep and goats was first introduced during the eighteenth century, although agriculture was the major focus of subsistence activity (Bailey and Bailey 1982:55). Navajo families moved camp seasonally, with settlements being located either in proximity to good grazing land (Brugge 1980:30) or good planting land (Dittert, Hester, and Eddy 1961:242). Sometime between 1750 and 1850, herding began to increase in importance and the subsistence economy slowly shifted to an emphasis on raising livestock (Bailey and Bailey 1982:59).

¶ 8 This change in subsistence orientation was in part a result of increasing hostilities with the Spanish, Mexican, and Euro-American colonists after 1800. A period of raiding and warfare continued from 1800 to 1864, when the Navajo were rounded up and sent to Fort Sumner for internment (Brugge 1986:144; Kelley 1982a:30-31). Prior to internment most of the Navajo country experienced a great population increase. The number of sheep raised by Navajo families also saw a large increase (Bailey and Bailey 1982:58-59).

¶ 9 Chaco Canyon, however, had become a major military route to Canyon de Chelly and the Chuskas (Kelley 1982a:30), and there are indications that the Chaco area was virtually abandoned between 1800 and 1863 (Brugge 1986:144). Brugge suggests that only a few poor Navajo families remained on Chacra Mesa, those with herds small enough to move around quickly and elude the military. Other Navajos continued to use Chacra for hunting and gathering while residing elsewhere (Brugge 1986:144). For those few families remaining, agriculture was almost completely abandoned in favor of economic activities of greater mobility, including hunting and gathering, stock raising, and raiding (Powers 1985). Finally, in the winter of 1863-64, all local Navajos were rounded up and sent to Bosque Redondo, near Fort Sumner for internment (Brugge 1984:79). The goal of internment, to teach the Navajo to be self-sufficient farmers, was a complete failure due to a combination of government incompetence and inadequate food, water, and firewood on the undersized and overpopulated Bosque Redondo reservation.

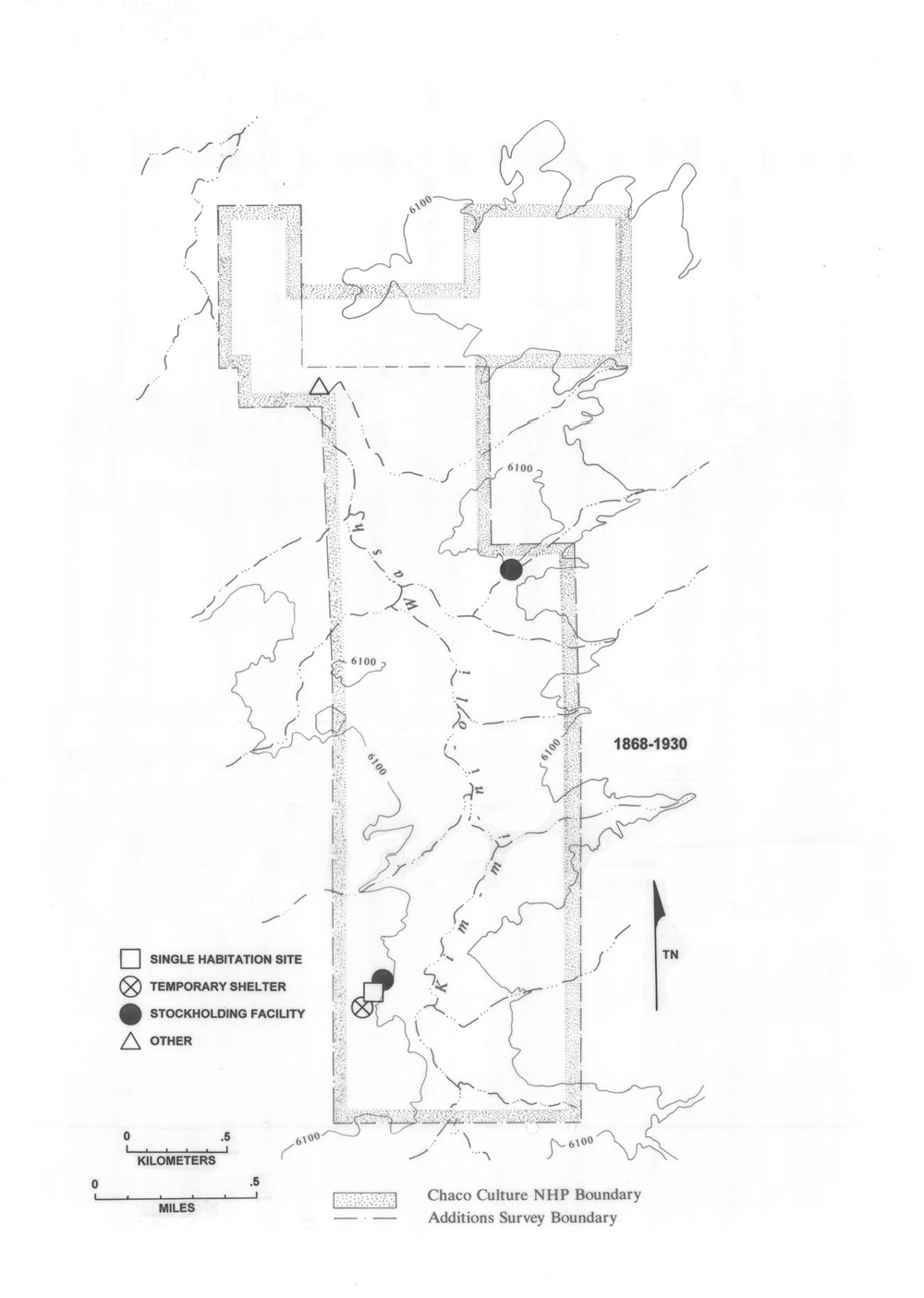

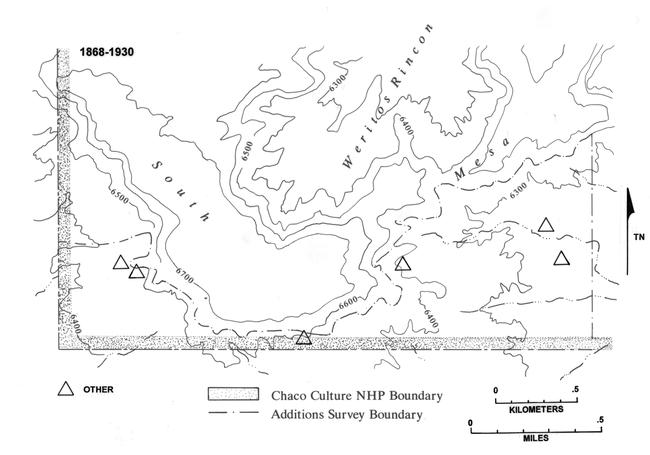

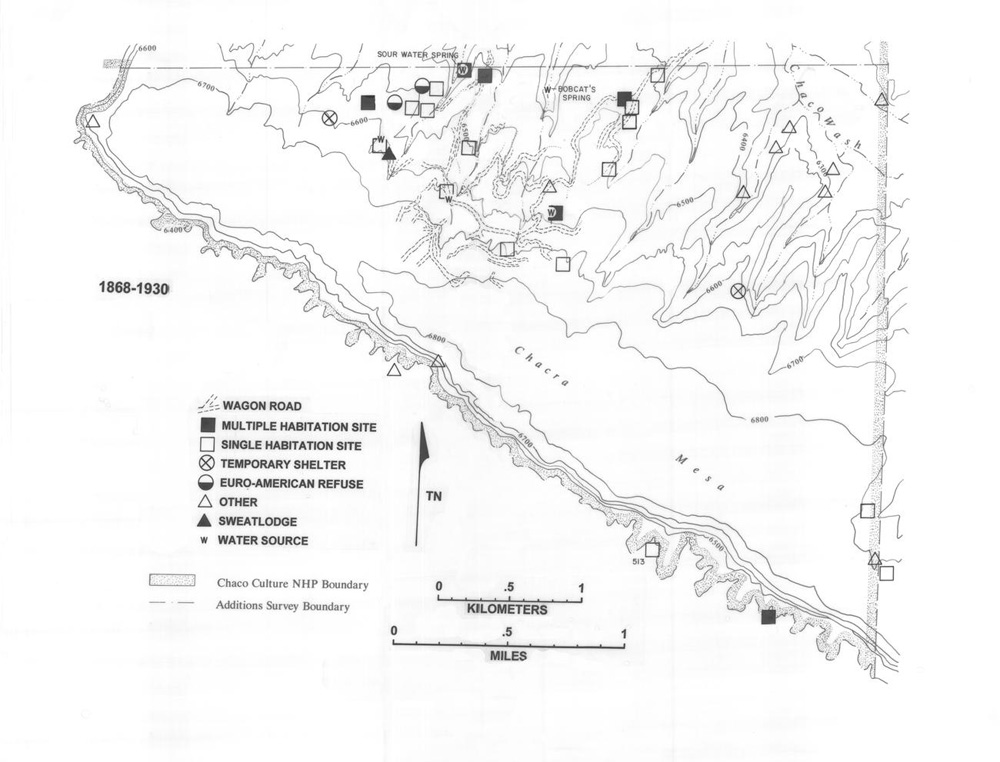

The Post-Bosque Redondo Period: 1868 to 1930

¶ 10 The Navajo were released from Fort Sumner in 1868, and many families returned to the Chaco area (Brugge 1986:144). Now herding was the primary economic activity, followed by farming, and then hunting (Bailey and Bailey 1982:97). The first Anglo stockmen began to settle in the area in the late 1870s (Brugge 1984:80), attracted by the available forage south of the San Juan River (Bailey and Bailey 1982:86-87). Spanish-American sheep herders soon followed, and the competition for the limited water and forage in the Chaco region began (Brugge 1986:144). Anglo settlement intensified with the arrival of the railroad in western New Mexico in 1881 (Bailey and Bailey 1982:130). The railroad increased the availability of manufactured goods and supplies, leading to a proliferation of trading posts in the area, including the Pueblo Bonito trading post established in 1897 by Richard Wetherill (Brugge 1980:161). During this period, trading posts became the primary agent of technological change in the Navajo country (Bailey and Bailey 1982:150). They not only provided the Navajo with greater access to Euro-American manufactured goods but also provided a market for wool and handicrafts (Kelley 1982b:49).

¶ 11 With a growing number of Anglo and Spanish-American ranchers competing for range land, the local Navajo were forced to acquire title to land through the Indian allotment program in the first several decades of the twentieth century. Anglos also laid claim to lands by filing their own homestead claims and leasing land from the railroad (Bailey and Bailey 1982:572; Brugge 1986:145; Kelley 1982a:24). Much of the range land was used by both groups: Spanish-American herders grazed their flocks in and around Chaco Canyon in the winter while Navajos used these lower areas as their summer range. With the increased emphasis on herding, Navajo habitation sites were usually seasonally occupied. Lower areas along drainages served as the summer range and Chacra Mesa with fuel wood and snow for water, was suitable for winter range (Kelley 1982a:197).

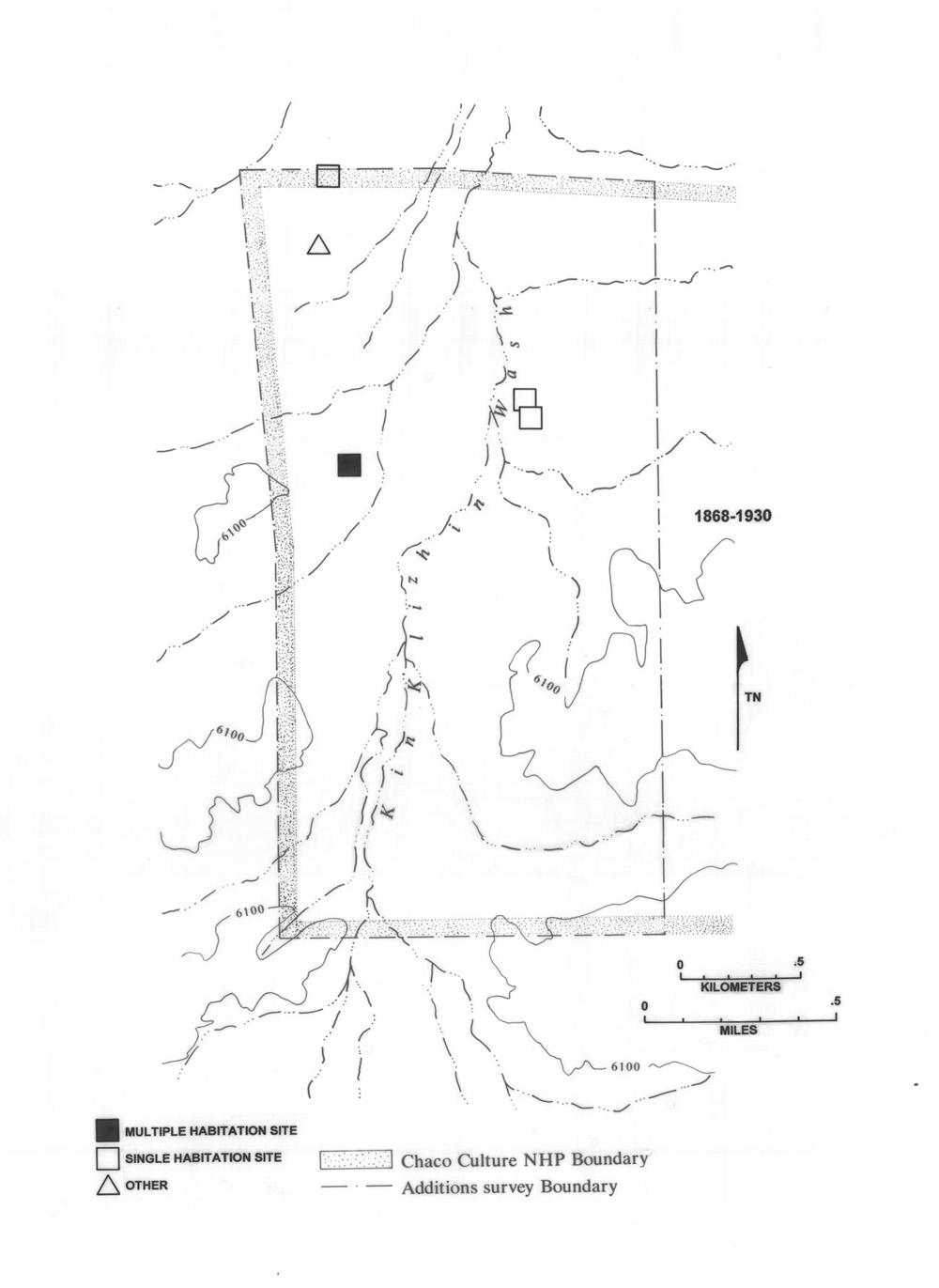

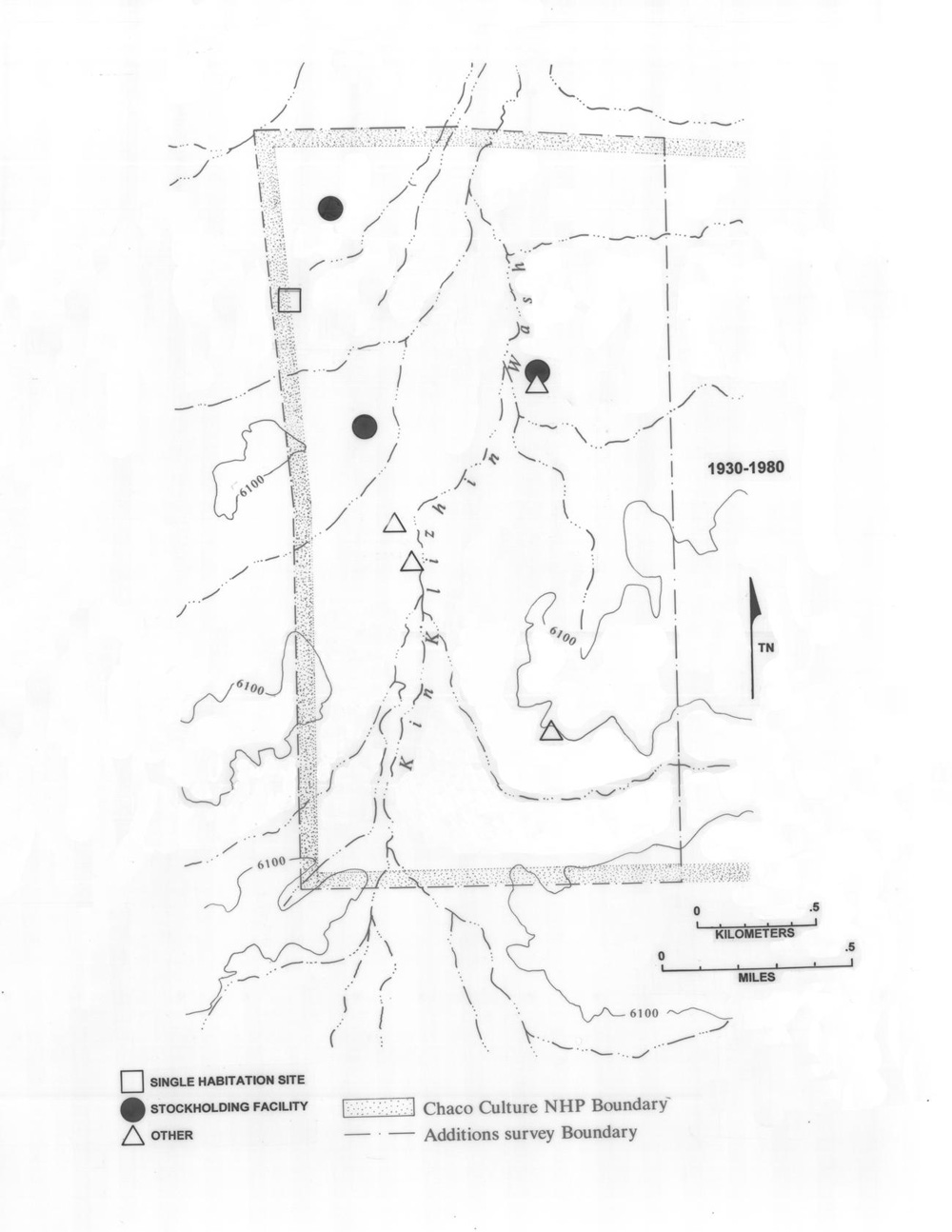

¶ 12 Most Navajos remained small-scale producers, but a few were able to build up large herds and hire others to care for their animals. The major Navajo owner of large herds in the Chaco region was Choche (Navajo George), who monopolized a large area of the range on and around Chacra Mesa from the late nineteenth century until around 1915 (Brugge 1986:145-146; Kelley 1982a:194-204). Most of the Spanish-American sheep herders in the Chaco area were partidarios working for Ed Sargent, the major Anglo rancher in the area. Partidarios were independent herders who leased sheep on shares (Brugge 1981:81). Partido contracts usually gave the owner of the stock a share of both the lambs and the wool produced by the flock. Ed Sargent’s sheep were first herded on Chacra Mesa in the mid-1920s (Kelley 1982a:91, 127).

¶ 13 A reorientation of the Navajo economy occurred between 1868 and 1930. Bailey and Bailey (1982: 25) argue that game and wild plant resources on the northern Chaco Plateau were greatly diminished by the end of the nineteenth century, with the result that hunting and gathering could no longer add substantially to the Navajo subsistence economy. The subsistence orientation based on agriculture and supplemented by herding and gathering was replaced by an increasing interaction with the non-Indian economy: the production of livestock and handicrafts for market, and wage labor became significant aspects of the economy (Bailey and Bailey 1982:217-218). What little trade occurred prior to 1880 had been, for the most part, a byproduct of subsistence activities. After 1880, trade was pursued more directly, with the manufacture of rugs and the production of livestock and wool geared toward the market.

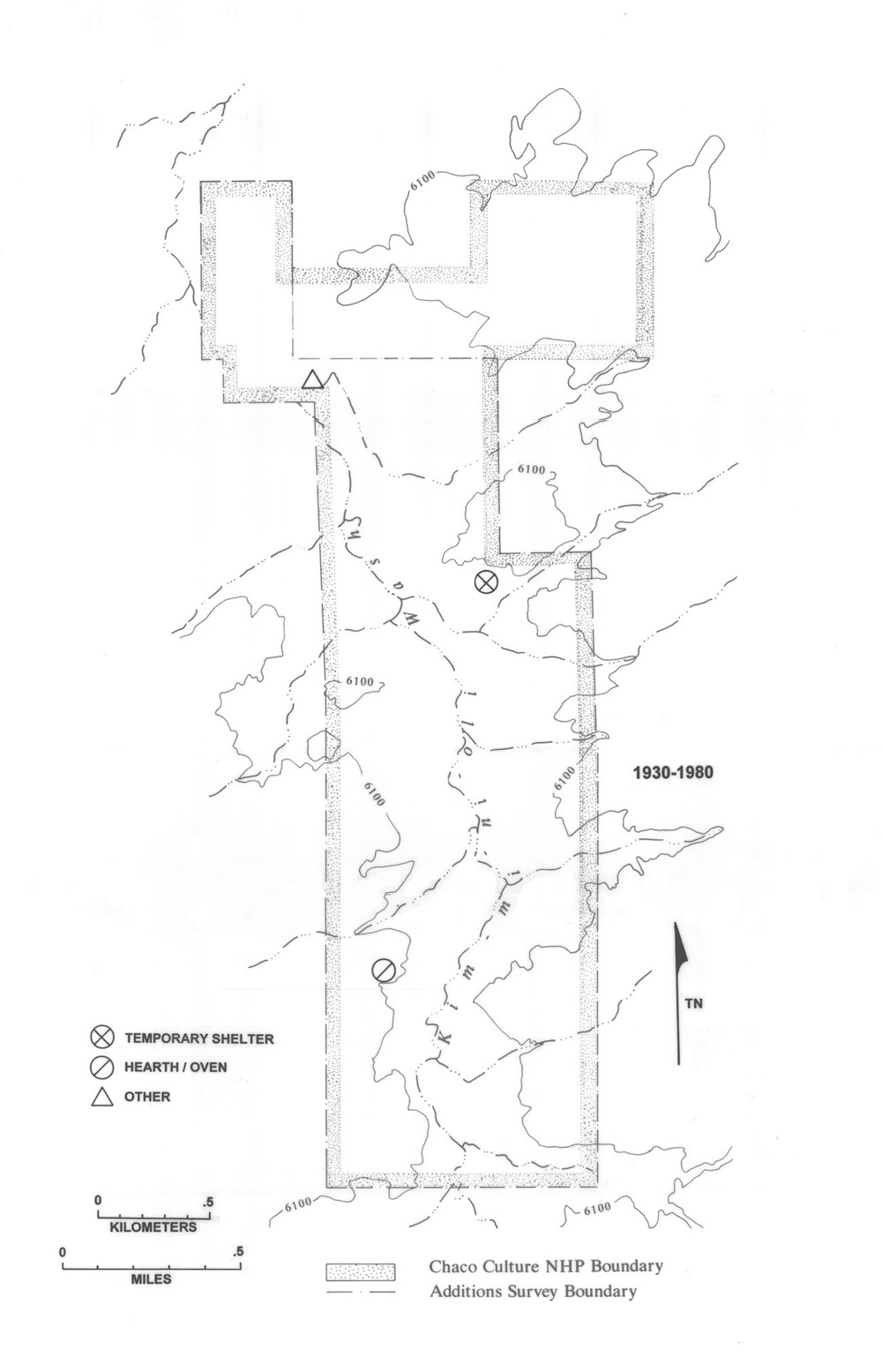

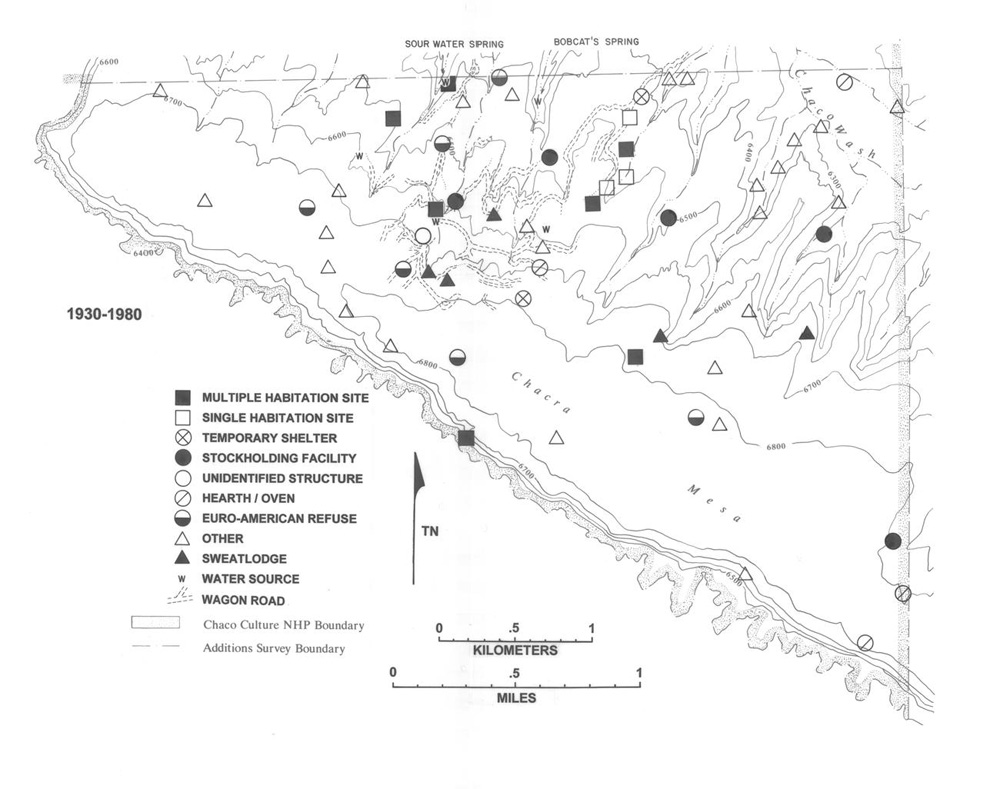

The Modern Period: 1930 to 1980

¶ 14 With the addition of wage labor, commercial herding, and craft production, Navajo families remained self-sufficient during the Post-Bosque Redondo Period. In the 1930s, however, Navajo economic self-sufficiency collapsed. This was primarily the result of the Great Depression and the federal livestock reduction program initiated in 1933 by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier (Bailey and Bailey 1982:374-390). The program consisted of three phases of stock reduction conducted in an effort to reduce the extensive overgrazing of Navajo lands. The livestock reduction program, however, had the effect of reducing herds to a level below that necessary for commercial herding (Bailey and Bailey 1982:425). Even without Collier’s program the size of herds would have been reduced as an unavoidable result of the overgrazing and loss of forage. Heavy overgrazing of Chaco Canyon had begun as early as the 1890s (Brugge 1980:166).

¶ 15 In 1933, the first of the three livestock reduction programs, requiring all livestock owners to sell an equal percentage of their livestock, reduced sheep holdings by 100,000 head. The burden of reduction continued to be shared by all Navajo families when the second phase was initiated in 1934. By now, however, the flocks of small herders were too small and economic conditions had changed so that the less affluent families were pressured to sell their only means of livelihood (York 1983:541). Their herds were reduced to a level below that necessary for commercial herding (Bailey and Bailey 1982:425). By the third phase of the program, in 1935, opposition was so great that only a small proportion of the proposed 200,000 sheep was sold (York 1983:541). The third phase of the program established a maximum herd size for each Navajo family and effectively destroyed most of the larger stock operations by the early 1940s. Bailey and Bailey (1982:448) note that with this the “focal point of the traditional Navajo dispersed extended family disappeared and the family dissolved into its component residence units.”

¶ 16 Reduction of herd size, division of family land holdings through inheritance, and an increased dependence on wage labor led to the replacement of seasonal mobility with year-round settlement at one location. Navajo families became dependent on wage labor in the 1930s, including the depression era public works programs (Brugge 1980:419). Navajos were hired to build fences around Chaco Canyon National Monument in the late 1930s and 1940s. The completion of this fencing project led to the exclusion of Navajo families from grazing their herds on monument lands and cut off the Chacra Mesa Navajos from Chaco Wash, an important water source for livestock (Brugge 1980:486). As a result, those portions of Chacra Mesa south of the monument, including the Chacra Mesa addition, were no longer attractive for habitation by Navajo families. Chacra Mesa and nearby areas were abandoned for range land along the Gallo and Escavada washes to the north (Kelley 1982a:227).

¶ 17 During World War II many Navajos joined the Armed Forces or left to work in war industries (Brugge 1986:147). Rapid population growth and stock reduction had destroyed the traditional herding basis of the Navajo economy. After stock reduction, herding could no longer provide the primary subsistence base for most families, and with the population continuing to increase, Navajos had to turn to sources of income other than herding and farming. By the 1950s wage labor was the major source of income for most eastern Navajo families (Bailey and Bailey 1982:431-432).

Site Dating

¶ 18 One hundred and fifty-eight Navajo and historic sites (188 components) were dated precisely enough for placement into one of the three temporal periods just described (Table 6.1). This is 43 percent of the recorded Navajo and historic sites in the Chaco Additions: eight (24 percent of the sites) in the Kin Bineola survey area, 10 (43 percent) in the Kin Klizhin survey area, 16 (53 percent) in the South Addition survey area, and 124 sites (45 percent) in the Chacra Mesa survey area.

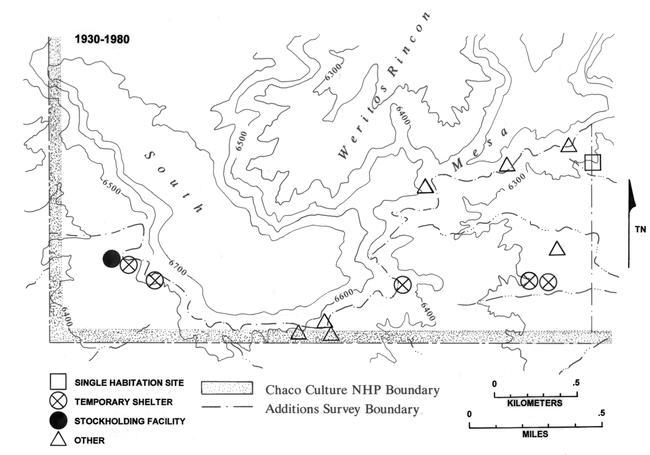

Table 6.1. Navajo and historic components by temporal period.

¶ 19 The largest number of sites were dated by the presence of historic artifacts and/or Navajo ceramics. Historic artifacts provided relative dates on 6 sites in Kin Bineola, 11 sites in Kin Klizhin, 5 sites in the South Addition, and 93 sites in the Chacra Mesa survey areas. Historic artifacts occurred on sites after about 1880 and were useful in placing many of the more recent sites; however, the date ranges on many artifacts were not precise enough for placement of sites into one of the three periods described. Ceramic dating was important in placing sites into the Pre-Bosque Redondo period, 1700 to 1863. The primary type recorded was Dinetah Gray, made between 1700 and 1850.2Dinetah Gray is now thought to have been produced between A.D. 1550 and 1800. See Dykeman et al. (2003: 388) One site in Kin Bineola, 3 sites in the South Addition, and 68 sites in Chacra Mesa survey area were dated by ceramics.

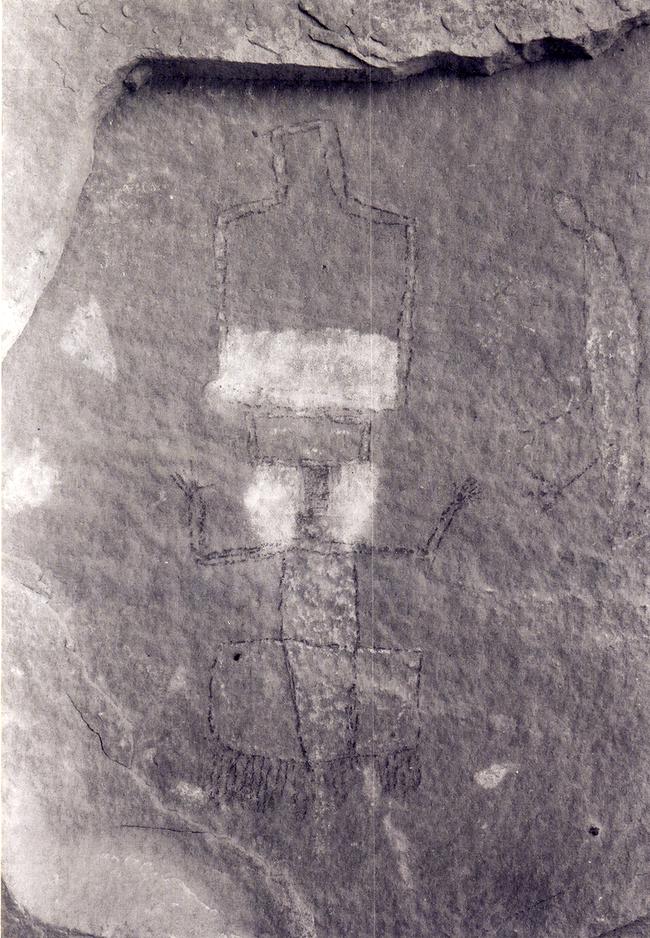

¶ 20 Rock art was also very useful in the tesmporal placement of sites, although in many cases it was not clear whether the artwork and inscriptions dated the site occupation as a whole or merely the rock art itself. Unless the site was a temporary camp or consisted solely of rock art, rock art was not used to infer dates of occupation of the site as a whole. It was very common for both Navajo and Spanish-American sheep herders to re-use an abandoned Navajo habitation site as a sheep camp at some later time. Dated inscriptions providing us with the exact year of a visit were found at 3 Kin Bineola sites, 5 Kin Klizhin sites, 14 South Addition sites, and 23 Chacra Mesa sites. In addition, pictorial designs such as Ye'i figures, trucks, wagons, horses, deer, and trains could be placed into broad temporal periods at 1 Kin Bineola site, 2 South Addition sites, and 17 Chacra Mesa sites.

¶ 21 Tree-ring samples were taken from a variety of wooden features at Navajo and historic sites, including hogans, corrals, wood piles, storage rooms, hearths, and sweat lodges. Fifty-three components at 46 sites were dated by this method. Few of the tree-ring dates are actual cutting dates: the majority are “vv” or “++vv” dates (see Appendix 6.1, Table 2 for key). In some cases, a number of samples from a single site or feature provided us with greater confidence in the interpretation of the dates. The tree-ring dates were all from Chacra mesa sites and are discussed in more detail below.

¶ 22 A final source of temporal information is occupation dates provided by the ethnohistorian as a result of informant interviews (see Chapter 8). These ethnohistoric data provide information on three sites in the Kin Bineola survey area, seven in Kin Klizhin, one in the South Addition, and seven sites in Chacra Mesa. Several of these sites were also discussed by Brugge (1986) in his archeological ethnohistory of Chacra Mesa.

¶ 23 In many cases dates from more than one of the methods were obtained for a particular site. Not surprisingly, the dates did not always support or complement one another. In some cases, multi-component sites were indicated. For single component sites, where a discrepancy between dates obtained by different methods occurred, a decision about which to accept was made on a site by site basis. Cutting dates from tree-ring samples, informant data, and inscriptions were generally accepted over historic artifacts or ceramic dates, depending on the quantity of the latter. On sites where both ceramics and historic artifacts (often post-1900 or post-1800) occurred, a date span based on the historic artifacts was generally accepted as more accurate. Ceramics on these sites may reflect some pre-1880 occupation, but they are more likely the result of continued use of the vessels after that time. Appendix 6.1, Table 2 summarizes the dating information for dated sites in the survey areas.

¶ 24 All three temporal periods are well-represented in the project area, with 50 components dated to the Pre-Bosque Redondo Period (1700 to 1863), 54 to the Post-Bosque Redondo Period (1868 to 1930), and 84 components dated to the Modern Period (1930 to 1980) (Table 6.1). This increase through time in the number of components appears to indicate increased usage of the survey areas from one period to the next, especially in light of the fact that the number of sites increases as the duration of the periods drops from 163 years to 62 years to 50 years.

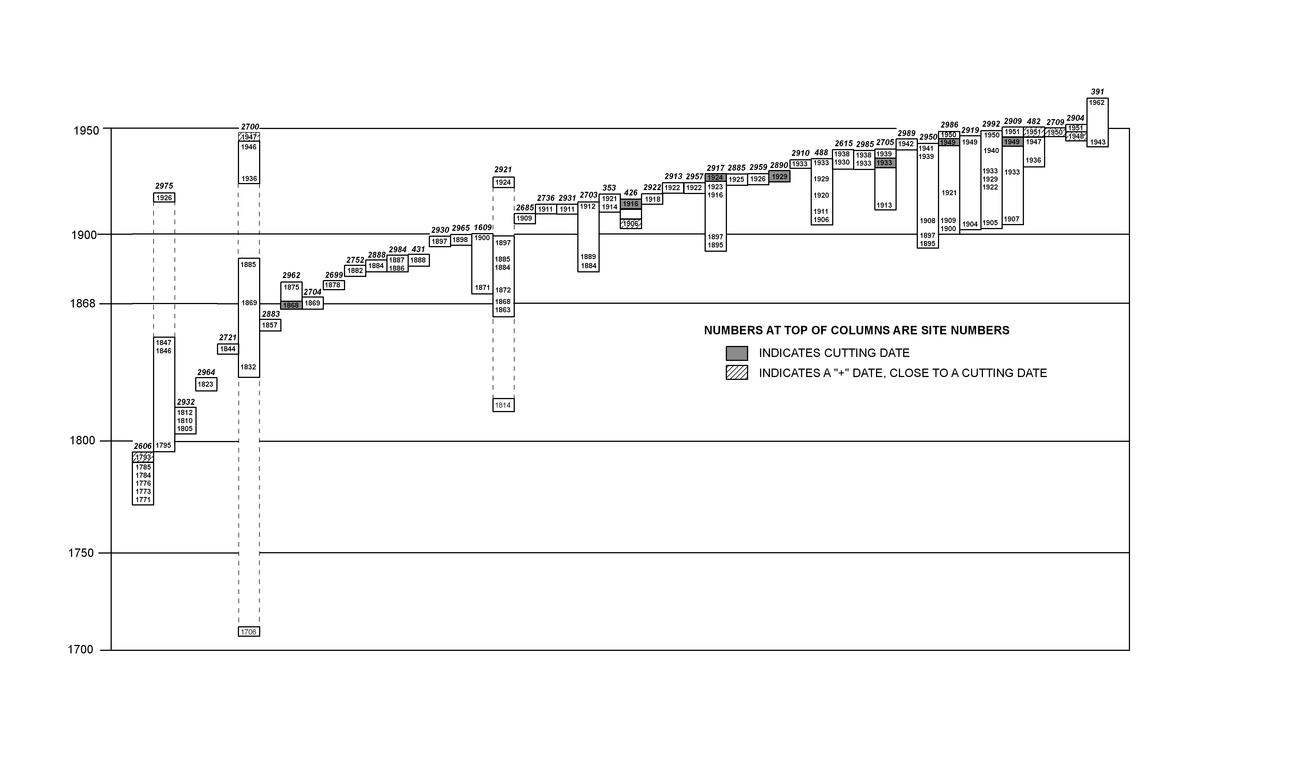

¶ 25 In Figure 6.1 the 46 tree-ring dated sites are arranged in temporal order from left to right. While the lack of preservation of wood suitable for tree-ring dating is certainly a factor in the extremely low number of dates prior to 1868, the difference in numbers of sites dating before and after Fort Sumner is substantial. While only seven sites produced dates prior to 1868, 42 sites produced dates after 1868. After 1868, there is a fairly continuous span of dates. Based on tree-rings, it appears that the Post-Bosque Redondo occupation of Chacra Mesa was continuous until around 1951.

|

Figure 6.1. Tree-ring dated sites in the Chacra Mesa survey area. |

¶ 26 The earliest dates were obtained from ceramics recorded at two small campsites (hearth sites) on Chacra Mesa, 29Mc 476 and 29Mc 479. Both sites are tentatively dated to 1600 to 1680 based on the presence of small numbers of Hawikuh Polychrome sherds (see Table 4.13). This date range is slightly earlier than that for any other known site in the Chaco Canyon area (Brugge 1986:141-142) and is therefore questionable without other supporting data. The earliest reliable tree-ring dates for Navajo sites in the project area are from 29SJ 2606, also on Chacra Mesa. A series of six dates from three hogans range from 1771 to 1793 (Appendix 6.1, Table 2). Interestingly, these dates cluster around the 1781 smallpox epidemic, after which Brugge (1986:143) sees little dwelling construction in Chaco Canyon and on Chacra Mesa. At least two hogans, however, were constructed in the 1780s and/or 1790s at 29SJ 2606.

¶ 27 Occupation of the Kin Bineola, Kin Klizhin, and South Addition survey areas appears to be primarily limited to the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The only exception to this is an early component of habitation site 29SJ 2782 in the South Addition, dated ceramically to between 1700 and 1850.

¶ 28 Use of the survey areas as early as the 1880s by Spanish-American sheep herders is indicated by a number of rock inscriptions, especially in the South Addition and Chacra Mesa survey areas. Seasonal use of the area by Spanish-American herders and Anglo ranchers, along with the Navajo, continued into the early 1940s.

¶ 29 The most recent of the tree-ring dates from Chacra Mesa indicate that most activity ended by 1951. It is expected that the Navajo occupation of the Chacra Mesa survey area ceased by the early 1950s as a result of the fencing off of Chaco Canyon National Monument. On Chacra Mesa, a corral at 29Mc 391 produced two dates; 1943++rGB and 1962v, indicating that a corral built during the 1940s was improved upon and reused, probably by a Navajo lessee who ran cattle on the mesa after 1962. Informant information on the other three survey areas indicates that Navajo occupation there also ceased by the mid-1950s. This is generally supported by temporally sensitive historic artifacts recorded in those areas.

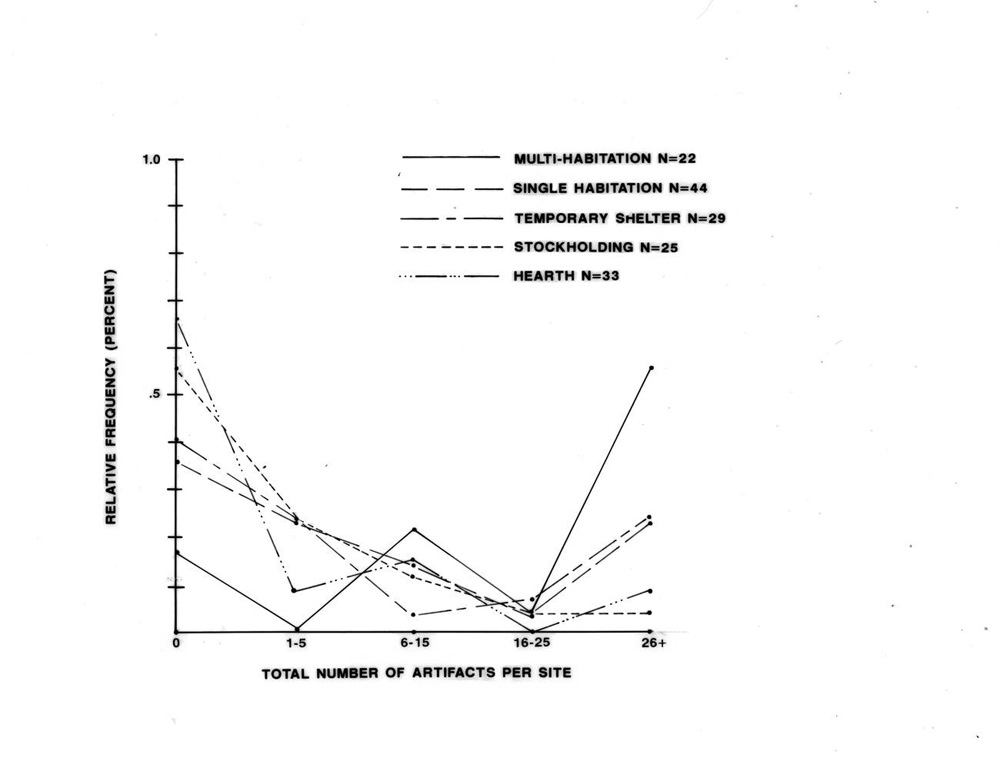

Sites

¶ 30 A wide variety of historic sites, mostly Navajo, were recorded by the inventory survey. These sites ranged from large, complex habitation sites to isolated sherd scatters and hearths. To organize this array of archeological remains, a typology was used which provides a basic functional classification of sites using only archeologically observable attributes. Sites were divided into three major categories: Habitations (two types), Temporary camps (six types), and Other sites (13 types) (Table 6.2). The distribution of these site components by time period is presented in Table 6.3.

|

Table 6.2. Number of sites of each type by survey area. |

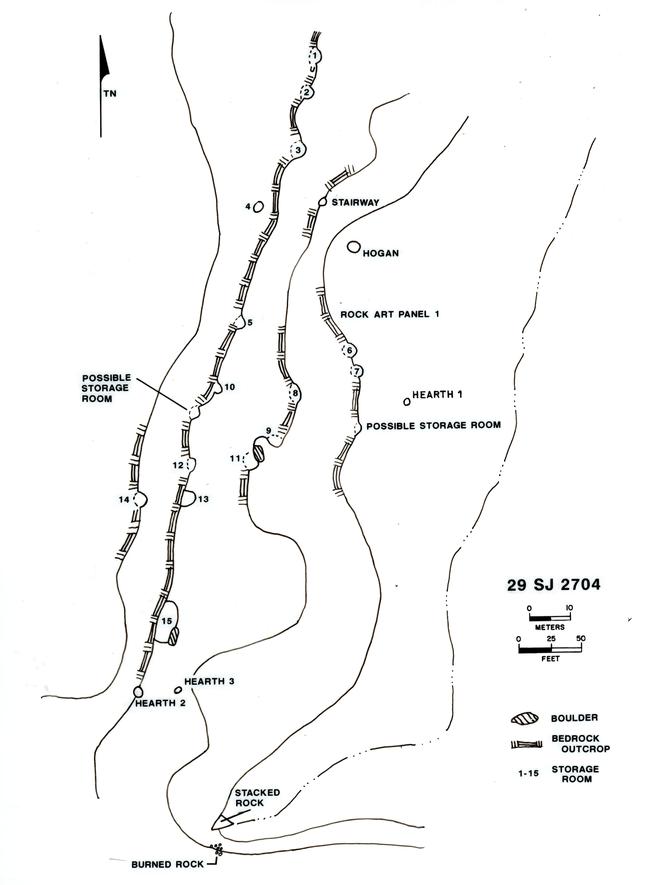

|||||

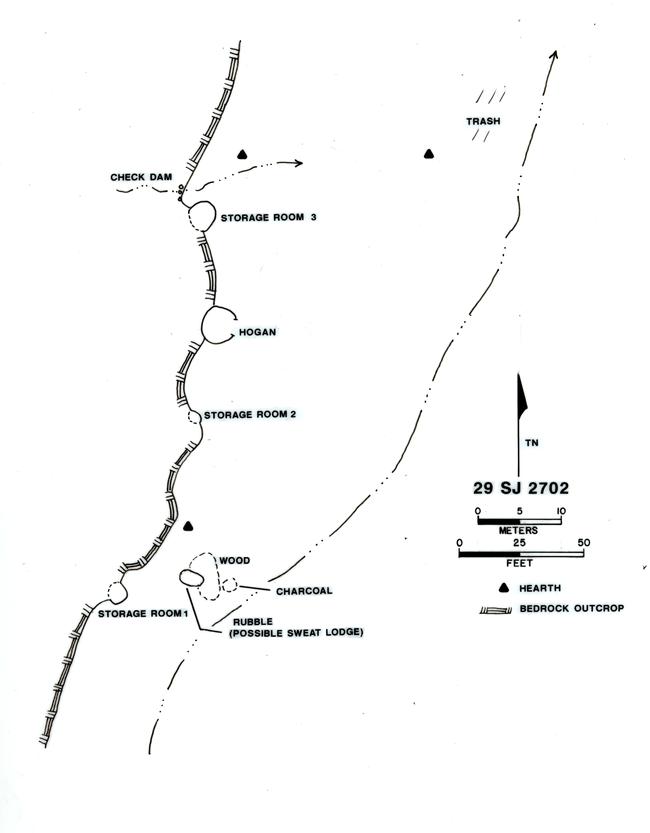

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site Type | Kin Bineola | Kin Klizhin | South Addition | Chacra Mesa | Total |

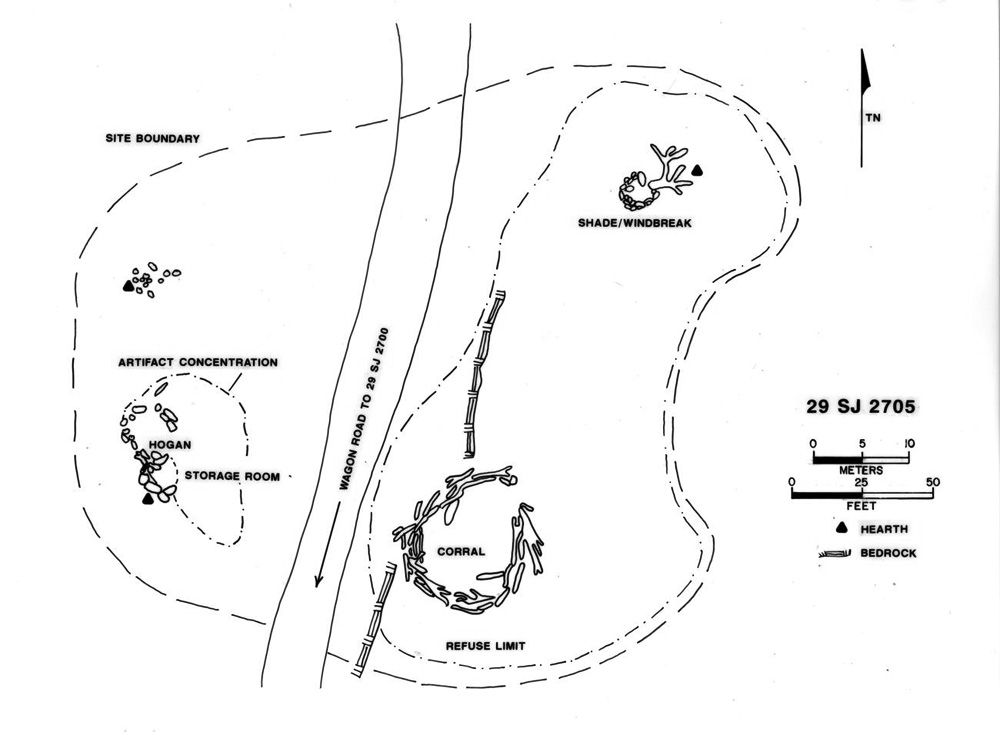

| Habitations: | |||||

| Single Habitation | 5 | 6 | 6 | 33 | 50 |

| Multiple Habitation | 1 | 1 | 2 | 26 | 30 |

| Temporary Camps: | |||||

| Temporary Shelter | 7 | 1 | 6 | 19 | 33 |

| Stockholding Facility | 8 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 27 |

| Unidentified Structure | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| Isolated Hearth/Oven | 5 | 2 | 1 | 27 | 35 |

| Sherd Scatter | - | - | - | 6 | 6 |

| Euro-American Refuse | - | 3 | - | 9 | 12 |

| Other: | |||||

| Rock Arta | 1/8 | 2/6 | 8/19 | 61/111 | 72/144 |

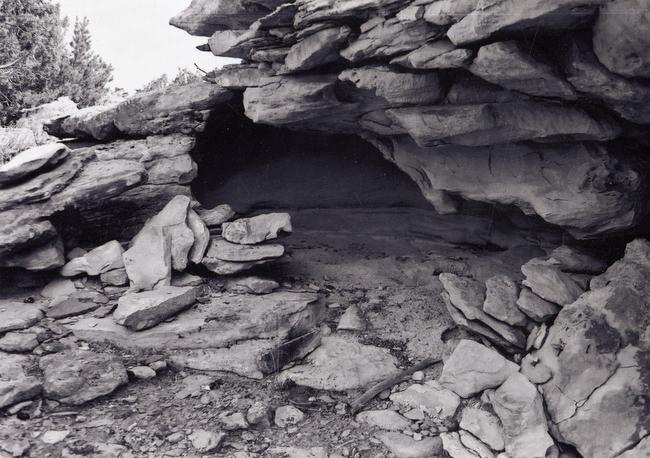

| Storage Facility | 1 | - | - | 14 | 15 |

| Sweat Lodge | - | - | - | 20 | 20 |

| Wood Cutting/Wood Pile | - | - | - | 9 | 9 |

| Road/Trail | 2 | - | - | 13 | 15 |

| Agricultural Field | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Water Control | - | 2 | - | 2 | 4 |

| Fence line | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Quarry | - | 1 | - | 3 | 4 |

| Burial | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Doll House | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Mining Claim Marker | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| Misc. Stone Features | 2 | - | 1 | 12 | 15 |

| Total: | 34 | 23 | 30 | 276 | 363 |

| aThe first figure is the total number of sites designated as rock art. The second figure is the total number of sites with rock art present. | |||||

Table 6.3. Number of components of each type by time period.

¶ 31 The 21 site types are differentiated by their primary cultural features. When present, habitation structures or temporary shelters were considered the primary features. In the absence of dwellings or shelters, structural features such as corrals, sweat lodges, storage rooms, or structures of unknown function were considered the predominant or primary features. Although the most striking features at many sites were rock art panels, other less imposing features which are assumed to be better indicators of site function were often used to place sites into a site type category. For example, all sites with rock art and hearths were classified as hearth sites and included in the temporary camp category. Even though a large number of the rock art loci were thereby classified as other site types, all rock art is included in the rock art summary later in this chapter.

¶ 32 Navajo homesites as well as campsites of shorter duration are generally referred to as “camps” in the literature (Bailey and Bailey 1982; Brugge 1986; Gilpin 1983; Kelley 1982a). Garrick and Roberta Bailey (1982:337) note that traditionally there were two major categories of Navajo camps: seasonal camps and temporary camps. A seasonal camp was the more permanent, albeit seasonal, residence of a family. There were two types of seasonal camps: summer camps and winter camps. Both were homesites which were reoccupied seasonally by the entire family. Because of the long-term occupation, or anticipated occupation, of these camps, dwelling structures were of a more permanent nature (Bailey and Bailey 1982:337).

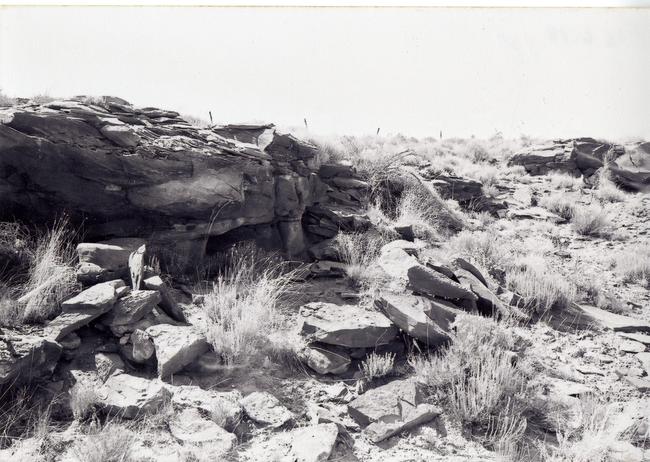

¶ 33 In contrast, a temporary camp was occupied by only a portion of the family on a short-term basis. A wide variety of temporary camps existed which were associated with economic activities of relatively short duration. They included sheep camps, farm camps, hunting camps, and plant gathering camps; all short-term satellite camps of a seasonal camp (Bailey and Bailey 1982:337-339). Temporary camps might also include the loci of a number of Navajo ceremonial activities, such as the Squaw Dance.

¶ 34 Sheep camps were the campsites used by either family herders or hired herders as they grazed their flocks around the more permanent seasonal camp. They were the most common of the temporary camps. Herders moved camp as often as every three days, although sheep camps with permanent dwellings were occupied for as long as two to four months at a time (Kelley 1982a:239, 246). Although temporary camps (such as sheep camps which were reutilized frequently) may have had hogans constructed on them, more often the dwelling structure was ephemeral, being a tent, brush shelter or ramada (Bailey and Bailey 1982:339). During the summer, sheep were bedded in the open and corrals were not needed, but winter sheep camps contained corrals of brush or stone (Kelley 1982a:239). On Gallegos Mesa, to the northwest of Chaco Canyon, sheep camps were found to exhibit a wide range of variability depending on the length of occupation. Archeologically, they ranged from small artifact scatters to sites which were virtually indistinguishable from single dwelling permanent camps (Gilpin 1983:969).

¶ 35 Farm camps were sometimes used by families who were primarily herders but also maintained fields. A farm camp consisted primarily of a shade and/or tent and usually a large horno with which to prepare corn during harvest time (Bailey and Bailey 1982:339). Hunting and plant gathering camps were of very short duration. Archeologically, they might be limited to small artifact scatters and possibly associated hearths.

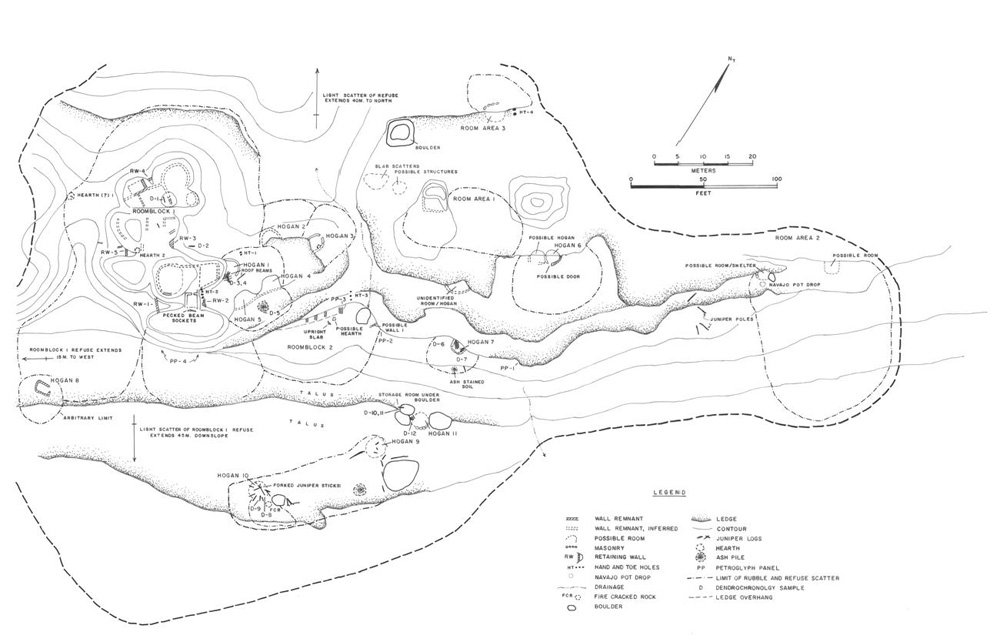

¶ 36 In order to avoid the confusion of using the term “camp” for both permanent and short-term sites, I have called all permanent or seasonal camps “habitations.” Habitations, therefore, may be summer or winter occupations. They are identified by the presence of dwellings, usually one or more hogans, and are often associated with ash or trash piles, corrals, and other domestic features. In some areas, such as at the base of Chacra Mesa near Chaco Wash where water was available year-round, habitation sites could be, and were, occupied during both summer and winter, although in most areas this was not possible.

¶ 37 In the present study, habitations have been divided into two types; multiple habitations and single habitations. Multiple habitations contain more than one habitation structure (usually hogans) and are considered to have been permanent seasonal camps occupied by extended Navajo families. Single habitation sites contain only one detectable habitation structure and are generally thought to have been occupied by a single nuclear family. Most single habitation sites are thought to be permanent seasonal camps. They were generally occupied six to seven months of the year (Kelley 1982a:246); however, as was previously noted, single hogans were at times constructed at temporary campsites (especially sheep camps) and therefore some of the single habitation sites recorded in the Chaco Additions were probably temporary camps rather than permanent. It is in part because of this variability in the function of single habitations that they have been separated from multiple habitation sites in this analysis. Although all the hogans at multiple habitation sites were not necessarily occupied at the same time, the greater number of dwellings (as well as other features) present may indicate that those sites were occupied over longer periods of time. Many probably functioned exactly like single habitation sites, but on the average it is expected that they had longer occupation spans. (This proposition is tested after the site types are described.) The category single habitation site is, therefore, the most difficult site type to categorize in terms of function.

¶ 38 Cultural affiliation could not always be determined for the sites recorded. The vast majority of the sites are presumed to be Navajo, including all of the habitation sites by virtue of the hogans present. Anglo- and Spanish-Americans used the inventory survey areas for herding, but the remains of this activity appear to be limited to temporary camps and rock art panels.

¶ 39 In many cases, the ethnicity of the herders using the camp is indicated by the presence of a hogan or by inscriptions or pictorial rock art. Sites which contained probable Spanish-American or Anglo components are listed in Table 6.4. Some of these sites also saw use by Navajos.

|

Table 6.4. Spanish-American and Anglo site components. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey Area | Site Type | Site Number | ||

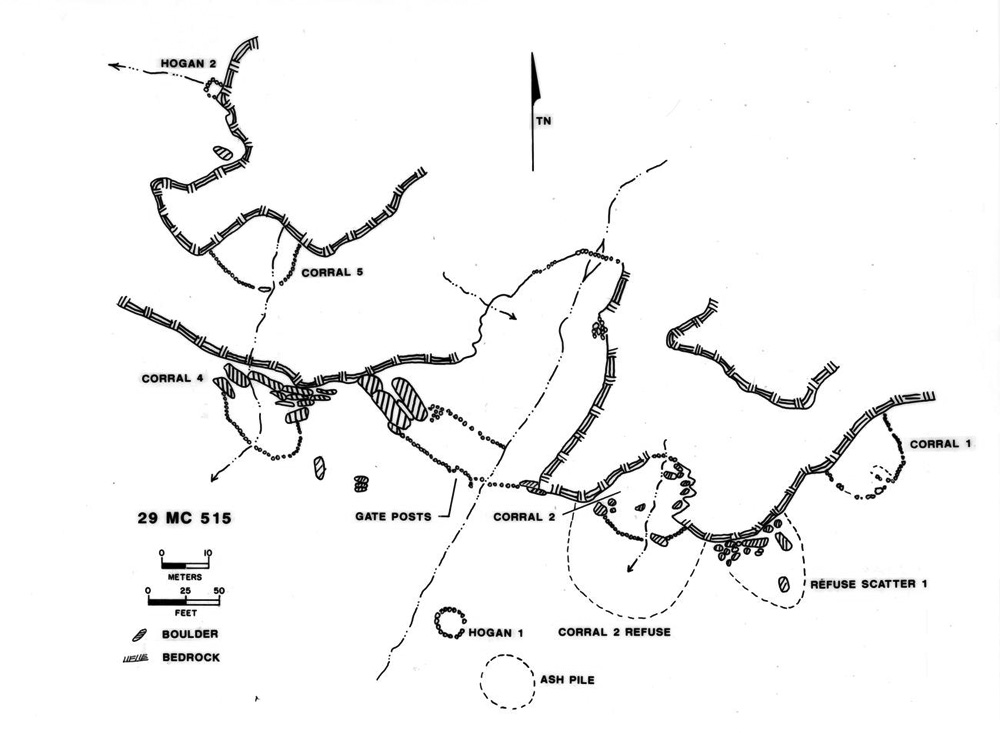

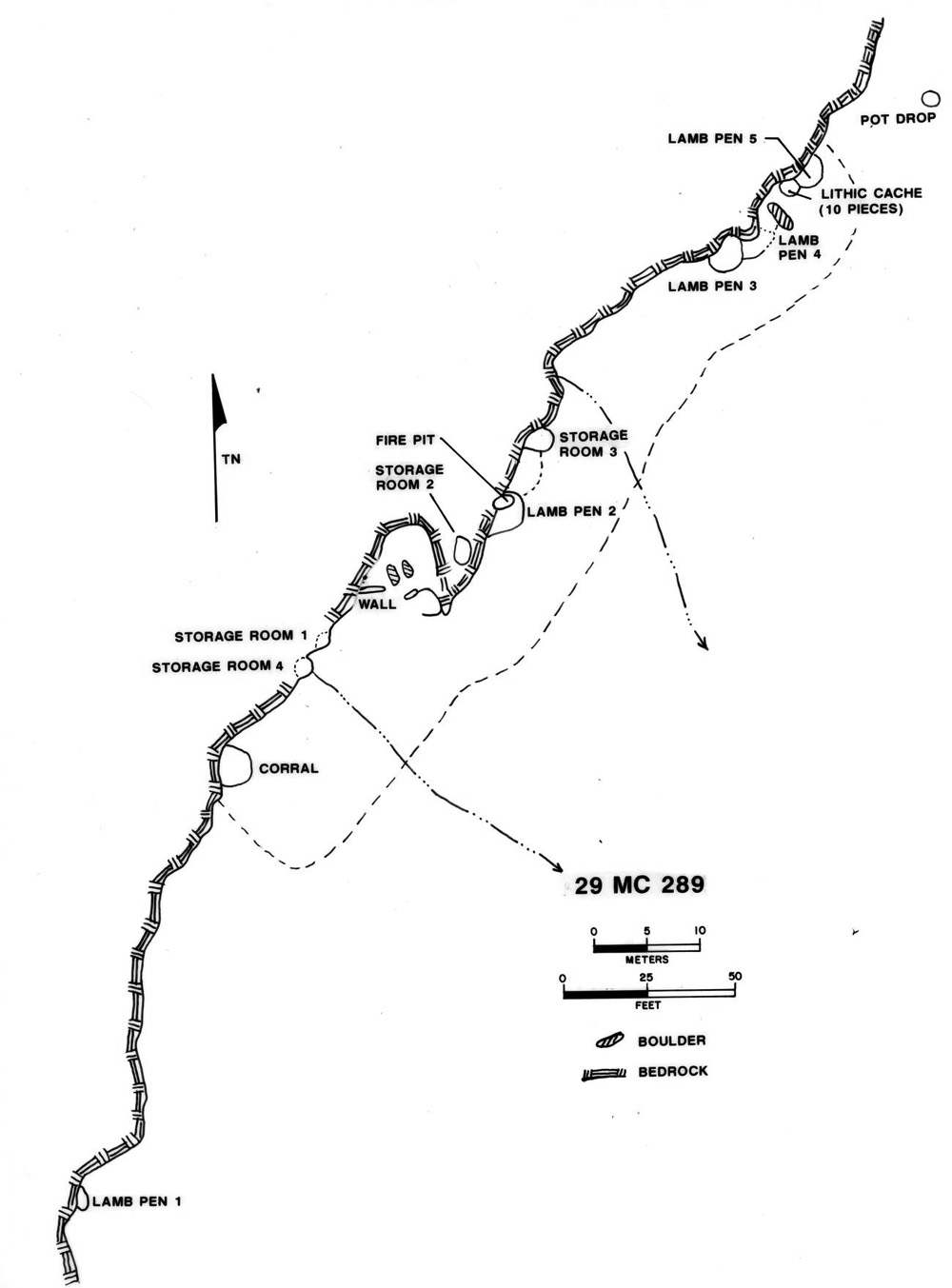

| Spanish-American Sites | ||||

| Kin Bineola | Rock Art | 29Mc 146 | 29Mc 264 | |

| Kin Klizhin | Stockholding | 29SJ 2459 | 29SJ 2471 | 29SJ 2484 |

| 29SJ 2491 | ||||

| Rock Art | 29SJ 2421 | 29SJ 2483 | ||

| South Addition | Stockholding | 29SJ 2822 | ||

| Temporary Shelter | 29SJ 2777 | 29SJ 2792 | 29SJ 2801 | |

| 29SJ 2837 | 29SJ 2838 | |||

| Unidentified Structure | 29SJ 2826 | |||

| Rock Art | 29SJ 2141 | 29SJ 2147 | 29SJ 2150 | |

| 29SJ 2772 | 29SJ 2805 | 29SJ 2821 | ||

| 29SJ 2828 | ||||

| Fence line | 29SJ 2836 | |||

| Chacra Mesa | Temporary Shelter | 29Mc 416 | 29Mc 431 | 29SJ 2891 |

| Hearths | 29Mc 424 | 29Mc 498 | ||

| Rock Art | 29Mc 391 | 29Mc 499 | 29SJ 206 | |

| 29SJ 2536 | 29SJ 2551 | 29SJ 2560 | ||

| 29SJ 2563 | 29SJ 2568 | 29SJ 2569 | ||

| 29SJ 2571 | 29SJ 2576 | 29SJ 2578 | ||

| 29SJ 2625 | 29SJ 2966 | |||

| Anglo-American Sites | ||||

| South Addition | Rock Art | 29SJ 2141 | 29SJ 2782 | |

| Chacra Mesa | Rock Art | 29SJ 203 | 29SJ 1620 | 29SJ 2571 |

| 29SJ 2922 | ||||

Habitation Sites

¶ 40 The largest and most obvious of the historic sites in the project area are Navajo habitation sites. They are recognized by the presence of at least one habitation structure, usually a hogan, although in some cases rectangular houses are present.

¶ 41 Habitation sites in the project area have been divided into two types: single habitations, those with one dwelling present; and multiple habitations, those with more than one. This distinction serves to separate the less complex habitation sites from those which are larger and, as a general rule, aids in distinguishing the size of the social group inhabiting the site. Each hogan at a Navajo habitation site tends to be occupied by a single nuclear family, with contemporary hogans at larger sites being occupied by separate families of the extended family group occupying that site (Brugge 1986:149; Kelley 1982b:51-52; Shepardson and Hammond 1970:44).

¶ 42 Of course, the problem of contemporaneity needs to be considered at multiple habitation sites. It is expected that the most favorable campsites were used over very long periods of time, sometimes continuously, sometimes intermittently. Therefore, the presence of more than one hogan at a site does not necessarily indicate occupation by an extended family. Abandoned hogans on some sites may have been used for storage or as animal enclosures, or may simply have sat unused. Conversely, the absence of surface evidence for more than one hogan at some habitation sites may also be misleading. Additional hogans may have deteriorated beyond recognition or have been robbed for building materials for more recent structures. In addition, the use of tents to accommodate additional family units at these sites often remains undetected without excavation (cf. Gilpin 1983:1427). In fact, in the present project area, informants have revealed that tents were used at some sites where no surface evidence remains (York: field notes3In 1985-1986 Fred York conducted interviews and site visits with Navajo informants at historic period sites identified by the Chaco Additions survey. His field notes, which were later used by Willow Roberts Powers to prepare Chapter 8 are referenced throughout this chapter. York’s field notes are on file at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park Archive at the University of New Mexico.). Because of this, the two types of habitation sites, single and multiple habitations, are not mutually exclusive in terms of site function, although in general, the distinction is a useful one.

Single Habitation Sites

¶ 43 Fifty single habitation sites were recorded in the project area: five in the Kin Bineola area, six in the Kin Klizhin area, six in the South Addition, and 33 in the Chacra Mesa area (Table 6.2). Ten single habitation site components date to the Pre-Bosque Redondo Period (1700 to 1863), 19 to the Post-Bosque Redondo Period (1868 to 1930), and five to the Modern Period (1930 to 1980) (Table 6.3).

¶ 44 The vast majority of these sites are small, containing few structures and features, with little, if any, historic trash associated. The general paucity of debris and outdoor features at these sites strongly suggests that their use was short-term and/or seasonal in nature. Structures associated with single habitation sites are generally limited to storage rooms and/or corrals, although a few ramada-type structures, sweat lodges, miscellaneous walls, and unidentified structures were also noted. The major feature types are defined and described in Appendix 6.2. At 11 of these sites (22 percent) the hogan or house was the only structure in evidence. The range of other features found at single habitation sites is presented in Table 6.5. These include all of the major feature types present at multiple habitation sites, although greater numbers and varieties tend to occur at the latter.

|

Table 6.5. Number of single habitation sites containing each feature type. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | Kin Bineola | Kin Klizhin | South Addition | Chacra Mesa | Total | Percent1 |

| Hogan | 3 | 5 | 6 | 33 | 47 | 94 |

| House | 2 | 1 | - | - | 3 | 6 |

| Storage Room | 1 | 1 | 2 | 18 | 22 | 44 |

| Corral | 1 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 18 | 36 |

| Lamb Pen | 2 | - | - | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Sweat Lodge | - | - | - | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Temporary Shelter | 1 | - | 2 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Unidentified Structure | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Stone Wall | 1 | 2 | - | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Storage Pit/Cist | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Hearth | 1 | - | - | 14 | 15 | 30 |

| Beehive Oven | - | 1 | - | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Ash/Trash Pile | - | 1 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 24 |

| Fire-altered Rock | - | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 18 |

| Rock Pile/Cairn | - | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 14 |

| Misc. Rock Feature | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| Water Control Feature | - | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | |

| Fence line | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| Burial | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Wood Pile/Scatter | - | - | - | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Sherds/Lithics | - | - | 2 | 16 | 18 | 36 |

| Euro-American Refuse | 2 | 5 | 1 | 19 | 27 | 54 |

| Rock Art | - | 2 | 1 | 8 | 11 | 22 |

| Trail | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Road Segment | - | - | - | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Doll House/ Pebble Cache | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Coyote Trap | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Quarry | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Chicken Coop | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Dog House | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 1The percentages shown in this column are the proportion of all single habitation sites (n=50) at which a given feature is present. For example, fire-altered features were found at nine sites or 18 percent of all single habitations. | ||||||

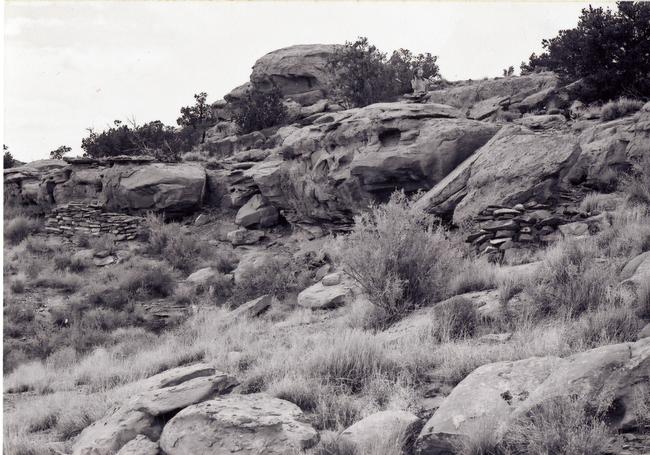

¶ 45 The most complex single habitation sites were found in the Chacra Mesa survey area. These sites contain much more accumulated Euro-American trash then most of those in other survey areas, as well as more numerous associated structures and features. One example is 29SJ 2704 (Figure 6.2), occupied between 1870 and 1930. It consists of a stone hogan, 15 to 17 possible storage rooms which were built into natural alcoves in the exposed Cliff House Sandstone, three to four hearths, a stone stairway between the lower and upper ledges of the cliff face, a rock art panel, and a scatter of Euro-American refuse. Such sites were utilized more extensively than the usual single habitation sites.

|

Figure 6.2. Plan view of 29SJ 2704, a single habitation site dated to 1870-1930. |

¶ 46 The distribution of features at single habitation sites is largely dependent on local topography. In all four survey areas most of the single habitation sites (74 percent) are situated against sandstone outcrops and ledges, or in rincons or small canyons which have formed in the Cliff House and Menefee Formations. Cliff faces and large scattered talus boulders provide ready shelter from the wind and solar radiation, and are often incorporated into the walls of hogans, storage rooms, and corrals. The use of these natural outcrops produces a more or less linear distribution of features along the base of the cliff or along the various exposed ledges, with directional orientation dependent on the facing of the exposed cliff or ledge (Figure 6.3). Scarps facing in each direction were utilized, although a preference for south and east facing is indicated: twenty-six single habitation sites (70 percent of those sites along cliff faces or ledges) are located at the base of east, south, or southeast facing outcrops.

|

Figure 6.3. Plan view of 29SJ 2702, a post-1930 single habitation site. |

¶ 47 A general easterly orientation of features on Navajo sites has been noted in previous research (Gilpin 1983:1435; Sciscenti and Greminger 1962:10) and is sometimes apparent in our project area in the placement of hogan entryways and the presence of ash/trash piles just northeast or southeast of the entryway. Woodcutting areas, and storage rooms which are not built against sandstone outcrops, are also found to the east or southeast of the hogan.

¶ 48 Open sites, located away from sandstone outcrops, exhibit an even stronger tendency for an easterly orientation, with entryways and activity areas toward the east. Corrals are sometimes located to the west or northwest, behind the hogan. Storage rooms and ash and trash piles are generally located just east of the hogan entryway. Ramada-like structures are fairly distant from the dwellings. Wagon roads which pass through open sites run east of the hogans. This generally easterly orientation is exhibited in the layout of 29SJ 2705, one the more complex single habitation sites (Figure 6.4).

|

Figure 6.4. Plan view of 29SJ 2705, a single habitation site dated to 1922-1960. |

¶ 49 The size of single habitation sites is extremely variable. The number of associated features obviously affects the overall size of the site, but another limiting factor is terrain. The small size of a cañoncito or rincon will sometimes dictate the clustering of site features. The areal extent of single habitation sites in the project area ranges from 15 to 47,500 m2. Site size was based on the area in which all related features and artifacts occur. It includes virtually all artifacts associated with a site, except isolated items occurring a substantial distance from other features or artifacts.

¶ 50 The average single habitation site area is 4,896 m2, but this figure is skewed by the existence of a few very large sites and a more informative statistic is the median site size, 1,880 m2. The largest sites are all located in the Chacra Mesa survey area. In fact, only one single habitation site larger than 4,550 m2 was located in another survey area (Appendix 6.1, Table 3). The exception is site 29SJ2799 in the South Addition.

¶ 51 The mean surface area of single habitation site components in each of the survey areas is broken down by time period in Table 6.6. Too few components are present in the three periods from the Kin Bineola, Kin Klizhin, and South Addition survey areas to allow meaningful comparisons. In the Chacra Mesa survey area, however, the largest sites appear to date to 1868 to 1930 and the smallest to 1930 to 1980. A comparison of site size for single habitations from all periods reveals an average of 6,367 m2 on Chacra Mesa; substantially larger than the average for any other survey area.

|

Table 6.6. Single habitation components: mean area in m2 by time period. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kin Bineola | Kin Klizhin | South Addition | Chacra Mesa | All Areas | ||

| 1700-1863 | ||||||

| No. of Comp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| Mean Area | 7,851 | 7,851 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 7,604 | 7,604 | ||||

| 1868-1930 | ||||||

| No. of Comp. | 1 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 16 | |

| Mean Area | 1,960 | 10,152 | 7,994 | |||

| Std. Dev. | 2,019 | 13,343 | 12,090 | |||

| 1930-1980 | ||||||

| No. of Comp. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Mean Area | 4,320 | 3,982 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 2,674 | 2,090 | ||||

| Other | ||||||

| No. of Comp. | 4 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 23 | |

| Mean Area | 987 | 320 | 2,235 | 1,857 | 1,654 | |

| Std. Dev. | 935 | 431 | 3,071 | 3,115 | 2,653 | |

| All Sites | ||||||

| No. of Comp. | 5 | 6 | 6 | 37 | 54 | |

| Mean Area | 830 | 1,487 | 2,621 | 6,367 | 4,896 | |

| Std. Dev. | 883 | 1,585 | 2,905 | 9,205 | 7,976 | |

¶ 52 Hogans were by far the most widely utilized form of dwelling at these sites, making up 47 of the 50 dwellings recorded (Table 6.5). The other three were called "houses," the distinction being in the shape of the floor plan, as similar construction methods were used in both types of dwellings. Hogans, the traditional Navajo dwellings, are ordinarily circular, subcircular, polygonal, or sub-rectangular in plan and normally contain a single room (Jett and Spencer 1981:14). Dwellings which are square-cornered, rectilinear in plan, with vertical walls were called "houses," although in some cases, such as when only a very low outline of the structure remained, the distinction was difficult to make. In the Chaco Country, the construction of true rectilinear houses began no earlier than the 1880s (Brugge 1980:94, 122, 142).

¶ 53 Most hogans (36 out of 47) located at single habitation sites are constructed of simple sandstone slab masonry (Appendix 6.1, Table 4). Unshaped slabs and occasionally larger blocks form circular or oval walls in most of the hogans (Figure 6.5). A few sub-rectangular and D-shaped hogans were recorded as well. Evidence of mortar and chinking stones was seldom present. Occasionally upright sandstone slabs were used in construction and very often a structure was built against a cliff or ledge, which formed part of a wall. Larger talus boulders were also used to form hogan walls at many sites (Appendix 6.1, Table 4). The extensive use of sandstone in hogan construction was clearly a product of its availability in the project area. The talus slopes and exposed outcrops in the extensive canyon system along the northeast side of Chacra Mesa, for instance, would have provided abundant construction material, to be obtained at minimal effort.

|

Figure 6.5. View of 29SJ 2700, a single habitation site. |

¶ 54 Two, two-room hogans were recorded at single habitation sites on Chacra Mesa, each containing two more-or-less circular or oval rooms. Both of these date to the 1700 to 1863 period and one was re-occupied during the 1868 to 1930 period. Although not common, double hogans have been recorded elsewhere on Chacra Mesa (Brugge 1978:43) and in Chaco Canyon (Malcolm 1939:10-11). Both 2-room hogans were constructed against sandstone outcrops, and the desire to take advantage of the large expanse of these natural features may have made the construction of these unusual dwellings convenient.

¶ 55 Interior hogan diameter at single habitation sites ranges from 1.7 to 5.3 m (Appendix 6.1, Table 4). Most hogans fall within the 2.6 to 4.6 range (mean 3.6; s.d. 0.99). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean floor areas of hogans from the three temporal periods rejects the null hypothesis that the are no significant differences (F [2, 28]=5.90, p <0.01). Over time the mean floor area increases from 7.1 m2 (s.d. 4.5) during 1700 to 1863, to 11.8 m2 (s.d. 5.5) during 1868 to 1930, to a mean of 16.0 m2 (s.d. 3.2) for hogans dated after 1930. Tukey’s family error rate between pairwise comparisons indicates that the mean hogan floor areas for the 1700-1863 period is significantly different from the floor area for the 1930 to 1980 period, but mean hogan floor areas for the 1700-1863 and 1868-1930 periods are not significantly different. Some of the smaller hogans were probably animal enclosures or human shelters intended for very temporary use rather than homes intended for habitation by an entire family (cf. Kelley 1982b: 51-52).

¶ 56 Wall height at present varies from one to nine courses with a maximum wall height of 1.3 m. On the average, walls currently stand three to four courses, or to a height of one-half meter (Figure 6.6). Brugge (1986:39) suggests that most of the low stone hogan rings probably represent wooden hogans. The low height of masonry in hogans in our survey area and the amount of rubble associated with them indicates that, indeed, the upper walls and roofs were constructed of wood or brush, probably of cribbed logs. Intact cribbed-log roofs were recorded at one single habitation site and one multiple habitation site in the project area.

|

Figure 6.6. View of hogan dated to 1945-1949 at 29SJ 2700, a single habitation site. |

¶ 57 Stone hogans were popular in northwestern New Mexico during the late nineteenth century (cf. Brugge 1980:120; Reher 1977:38; Sciscenti and Greminger 1962:10; Sessions and Williams 1979:204) and were in use in the Chaco area as early as the mid-eighteenth century (Brugge 1986:133). The earliest tree-ring dated stone hogan in our project area was constructed in the late eighteenth century. It is located at a multiple habitation site, 29SJ 2606 (Appendix 6.1, Table 2).

¶ 58 Previous research has indicated that dwellings built before the internment at Fort Sumner (1864 to 1868) were often the more traditional forked-stick hogans (Brugge 1980:27; Keur 1941:69; Vivian 1960:8), and that this dwelling form became extremely rare by the early twentieth century (Brugge 1980:266). Only four possible forked-stick hogans were recorded at single habitation sites, all in the Chacra Mesa survey area. Two are dated by ceramic association to the period 1700 to 1863; the other two are dated to 1868 to 1930. No standing forked-stick hogans were located. All forked-stick hogans recorded were indicated by the presence of circular sandstone slab foundations with either ash or collapsed branches indicating a wooden superstructure. One contains an interior masonry storage bin. Only five masonry hogans at single habitation sites contained evidence of internal features: three had internal hearths, one contained an internal storage bin, and one an interior cist (Appendices 6.2 and 6.1, Table 4).

¶ 59 The three houses located at single habitation sites were in the Kin Klizhin and Kin Bineola survey areas. All are poorly preserved, small rectangular masonry structures. At 29SJ 2484 only a foundation of large boulders remains, with evidence of a possible stone floor and a doorway on the east side. The houses at 29Mc 225 and 29Mc 284 have simple sandstone masonry walls.

¶ 60 Storage rooms were built using the same construction techniques as hogans, but they are smaller and more varied in floor plan. All but one are masonry, utilizing simple sandstone slab construction with slabs stacked horizontally and sometimes vertically. A single brush enclosure within an overhang was also identified as a possible storage feature by the field crew. The natural crevices and alcoves in sandstone ledges were heavily utilized in the construction of storage rooms. Often only a small wall was needed across the front of an appropriately-sized crevice. Storage features of this type were used historically by the Navajo, usually to store corn, beans, dried squash, and dried melon (Hill 1938, cited in Malcolm 1939:15-16).

¶ 61 In many cases it was not possible to be sure these rooms were used for storage. Distinguishing storage rooms from lamb pens was a major problem during the project, in that the two feature types were archeologically indistinguishable. Survey crews tended to categorize small masonry structures built against sandstone outcrops as storage rooms. Later, many of these were identified by Navajo informants as lamb pens. Informants indicated that still others apparently served as dog houses (York: field notes). As such, when informant information was not available, the field assessment of whether a structure was a storage room or lamb pen was accepted for the present analysis; the accuracy of those assessments, however, is questionable. There appears to have been no significant change through time in the use of storage features (Table 6.7). Evidence of subsurface storage pits or cists was found at only three single habitation sites, although they are known to have been a popular form of storage (Hill 1938:42, 43; Jett and Spencer 1981:187; Winter 1983:485). Their general absence from feature lists at sites in the project area is most likely a result of their lack of visibility.

|

Table 6.7. Major features present at dated single habitation components. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1700-1863 | 1868-1930 | 1930-1960 | |

| No. of Habitation Components | 10 | 16 | 5 |

| No. with Corrals | 1 (10%) | 9 (47%) | 4 (80%) |

| No. with Storage Facilities | 7 (70%) | 11 (58%) | 3 (60%) |

| No. with Wood Cutting Areas or Wood Piles | 2 (20%) | 2 (11%) | 0 |

| No. with Sweat Lodges | 1 (10%) | 4 (21%) | 1 (20%) |

| No. with Temporary Shelters | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (20%) |

| Note: Percentages shown in this table represent the proportion of components of a given time period at which a given feature type is present. For example, in the 1930-1960 time period, four (80%) of five single habitations have corrals. | |||

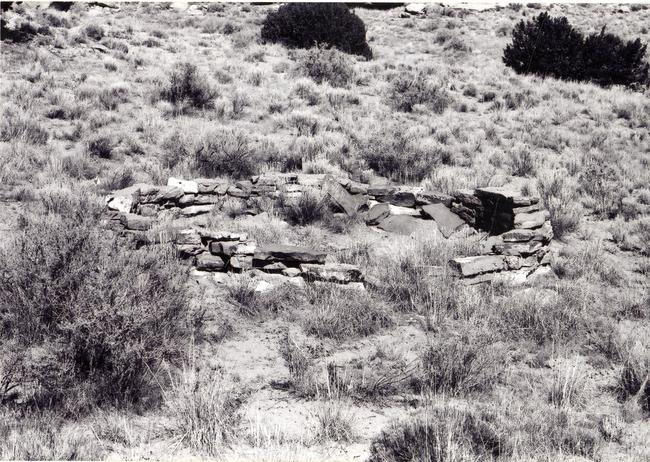

¶ 62 Corrals are present at 18 of the 50 single habitation sites (36 percent) and lamb pens at three (Table 6.5). Two corrals were found at each of five sites. All other sites have only one corral. Corrals, too, were not always clearly identifiable from the extant remains. Six of those recorded at single habitation sites were tentatively identified, based on the presence of incomplete or badly deteriorated walls. The two corrals at 29Mc 279 are just small enough and so poorly preserved that they may have actually been hogans. Most corrals were built of sandstone rubble (Figure 6.7), although sometimes brush was incorporated into walls. Many corrals in the survey areas were probably constructed of brush and timber, and are now indistinguishable. Large talus boulders were often used in forming the walls, and in 17 of the 24 corrals a ledge or rincon formed part of the enclosure. Only seven of the corrals are free-standing. Shape and size are extremely variable. The largest is at 29SJ 2984, where a barricade constructed of masonry and brush closes off the end of a rincon, an area of 63 by 30 m. Another smaller corral is also present at this site. Site 29SJ 2700 had four lamb pens surrounded by a corral (Figure 6.8).

|

Figure 6.7. View of corral at 29SJ 2478, a single habitation site dated to 1910-1920. |

|

Figure 6.8. View of lamb pen at 29SJ 2700, a single habitation site with a component dated to 1945-1949. |

¶ 63 The number of single habitation components with corrals present increases through time from 10 percent during 1700 to 1863, to 47 percent during 1868 to 1930, and 80 percent after 1930 (Table 6.7). On the surface, this would appear to indicate an increase through time in the number of families owning livestock; however, how much of this is due to differential preservation is not known. Corral preservation is certainly better for the later periods. Changes in site function and herding practices may also have contributed to the observed increase in the occurrence of corrals.

¶ 64 The remains of sweat lodges were found at six of the single habitation sites on Chacra Mesa. Two of these sites had evidence for two sweat lodges; the other four had only one. Four of these dated to 1868 to 1930. One sweat lodge was dated to each of the 1700 to 1863 and 1930 to 1980 periods (Table 6.7). No standing structures were found, although in most cases several juniper poles were noted in association with large stock piles of fire-cracked rock and rock heating hearths. All sweat lodges were located at least 25 m from the nearest hogan. Rincons or curvature of the sandstone outcrops were often used to obscure the view toward a sweat lodge from the hogan and general activity area.

¶ 65 Two open summer shelters were recorded at single habitation sites, both in the Chacra Mesa survey area. Each consists of an arc of stone and brush, forming a windbreak or shade, opening to the east. In one, several upright posts were used to hold up the brush and deadwood walls. Four other possible windbreaks or shades were identified by the presence of semi-circular areas of sandstones. Of these four, two were found in the South Addition, one in Chacra Mesa, and one in the Kin Bineola survey area. A tent platform at 29Mc 416 on Chacra Mesa was identified by the ethnohistorian.

¶ 66 Three masonry structures of unknown function were also recorded at two single habitation sites (Appendix 6.1, Table 4). Smaller domestic features associated with the single habitation sites included outdoor hearths, ash piles, trash piles, concentrations of fire-altered rock, unburned rock piles and cairns, scatters of cut wood, and historic ceramics or lithics. Hearths were often located within the general activity area in front of a hogan, although locations distant from dwellings were not uncommon.

¶ 67 Ash piles, which excavations elsewhere have shown to be consistently associated with hogans on permanent campsites (Gilpin 1983:1435), were found at 12 (24 percent) single habitation sites (Table 6.5). They tend to be located immediately east, southeast, or northeast of the hogan entrance and contain fragments of burned bone, metal, glass and small sandstone spalls or slabs as well as ash and charcoal. Their size is variable, as they are often combined with, or converge with, scatters of trash. Euro-American trash is generally not present in large quantities. Many of the earlier sites contain scatters of historic Navajo and/or Puebloan ceramics, or pot drops.

¶ 68 Rock piles, scatters, and areas of fire-altered rock are also found in all areas of single habitation sites. Wood features at single habitation sites include a possible wood chopping area and six scatters of cut or milled wood. The wood chopping area is located directly southeast of the hogan it is associated with. Wood scatters show no particular placement on sites. Wood features date to both 1700 to 1863 and 1868 to 1930 (Table 6.7).

¶ 69 Three single habitation sites contained the remains of possible Spanish-style beehive ovens. In all cases, the features were collapsed concentrations of burned and unburned sandstone slabs and the identifications are tentative.

¶ 70 Evidence of child’s play was found at two sites in the form of miniature houses or hogans. At one of these sites, 29SJ 2582, a doll house was constructed on the cliff ledge behind the hogan and a series of wind erosion pockets along the same ledge were filled with sandstone spalls. Another doll house at 29SJ 2968 measures 0.4 m in diameter and although it is now largely collapsed, one can discern that it was originally roofed with small branches. At a third site, 29SJ 2959, a large pile of sandstone concretions is located under a ledge near the hogan. Brugge (1986:127) suggests that such caches of stones may be children’s playthings, as they appear to have no other useful purpose.

¶ 71 The presence of Navajo burials is indicated at three single habitation sites. They are described with the other burials later in this chapter.

¶ 72 Features which were found rarely at single habitation sites include check dams, wire fence lines, a coyote trap, a sandstone quarry, and a talus boulder exhibiting axe-sharpening grooves. Trails leading up (or down) sandstone ledges were found at three single habitation sites and segments of historic wagon roads were visible at five sites.

¶ 73 Finally, rock art and/or inscriptions were found at 11 of the 50 single habitation sites. Because this feature type makes up such a large proportion of the features and site types in the project area, all rock art is discussed in a later section of this chapter.

Multiple Habitation Sites

¶ 74 Thirty multiple habitation sites were recorded in the project area (Table 6.2). These multiple habitation sites contain from two to twelve habitation structures. Most (77 percent), however, have only two or three hogans or houses (Appendix 6.1, Table 5). Sites in this category are generally considered to have been more heavily used than the single habitations, as indicated by the presence of substantially greater quantities and varieties of cultural features and debris. (This is detailed in Testing the Site Typology, below). Multiple habitation sites for which ethnohistoric information is available served as either permanent “winter” camps or sheep camps which were used over an extended period of time. Nine of the multiple habitation site components were occupied during 1700 to 1863, seven during 1868 to 1930, and seven during 1930 to 1980 (Table 6.3). Several of these sites were occupied during more than one of these periods (Table 6.1).

¶ 75 Like single habitation sites, the more complex multiple habitations are located in the Chacra Mesa area, indicating greater use of that area for winter or permanent camps. Some of the most complex were campsites of Choche’s family and his descendants. Choche was the major livestock owner in the area (Brugge 1986:145). The most simple sites in the multiple habitation category include four sites with only two hogans, two sites with only hogans and a corral, and one site with only three hogans and a scatter of sherds. Sites such as these are probably more similar, functionally, to the single habitations than to most other multiple habitation sites. They may have served as sheep camps.

¶ 76 The most common structures recorded on multiple habitation sites were hogans, storage rooms, and corrals. Rectangular houses, lamb pens, ramadas or shelters, sweat lodges, and unidentified structures are also present, but in much lower numbers (Appendix 6.1, Table 5). An array of additional non-structural domestic and production features is also present. Outdoor hearths, ash and/or trash piles, burned and unburned rock concentrations, sherd and lithic scatters, and Euro-American refuse are predominant. They are tabulated by survey area in Table 6.8. Features found at multiple habitation sites which were not found at single habitation sites include coal mines, developed seeps, the possible base of a feeding trough, and a tent platform and peg. The presence of available coal and seeps at some of these sites was probably an important factor in the more permanent use of those locations.

Table 6.8. Number of multiple habitation sites containing each type of feature.

¶ 77 As Brugge (1986:5) notes in earlier work on Chacra Mesa, the sheltered heads and rincons of canyons on the northeastern side of Chacra Mesa provided especially favorable environments for residence because they occasionally contained springs or groundwater near the surface and protection from sun and wind. Sandstone outcrops, cliffs, ledges, and large talus boulders were heavily utilized in construction, being incorporated into hogan, corral, and storage room walls. Almost all of the 30 multiple habitation sites were located in areas protected by sandstone cliffs or ledges (Figure 6.9; Appendix 6.1, Table 5). Thus, as was the case for single habitation sites, site layout is affected by the use of available outcrops for construction.

|

Figure 6.9. Plan view of 29Mc 515. |

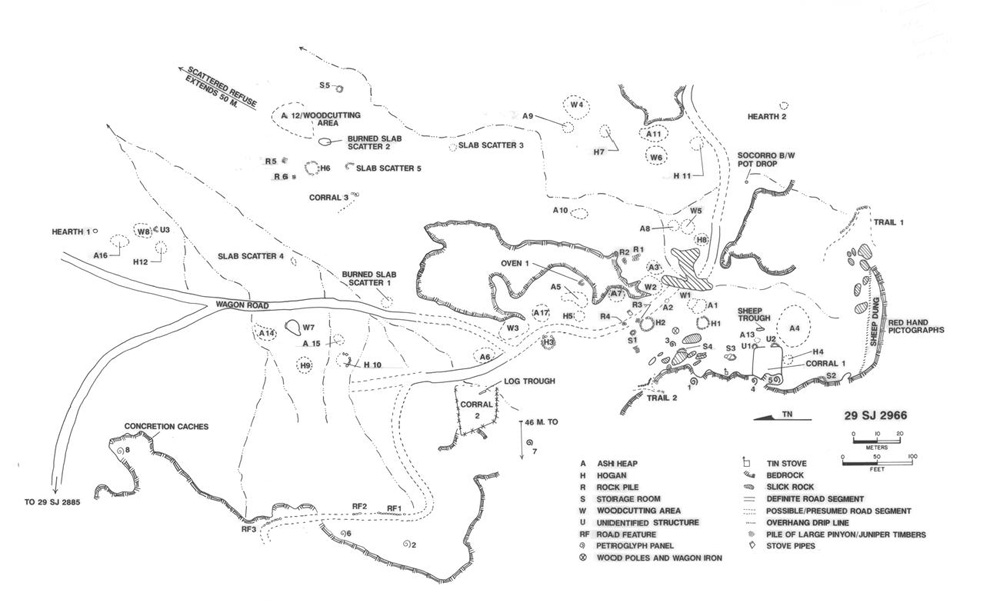

¶ 78 There is no real pattern to the placement of hogan or household complexes on these sites. Hogans are scattered across sites along the base of outcrops or are in the open. Spacing between hogans (or houses) is extremely variable, ranging from less than 5 m to 128 m between nearest neighbors. Distances of 20 to 50 m are common. On larger sites, such as 29SJ 2966 and 29SJ 2606, where clusters of hogans and associated features are found, each cluster is likely a distinct temporal component (Figures 6.10 and 6.11). Features such as ashpiles and trash scatters, wood chopping areas, and sometimes, hearths are often associated with particular hogans, being located in front, usually to the east, northeast, or southeast of the hogan. Other features, such as corrals and storage rooms, are usually located apart from the dwellings.

|

Figure 6.10. Plan view of 29SJ 2606, a multiple habitation site dated to 1776-1850. Roomblocks 1 and 2, and Room Areas 1-3 are from an earlier Anasazi occupation of the site. |

|

Figure 6.11. Plan view of 29S 2966, a multi-component multiple habitation site which served as a major winter residence between 1940 and the early 1950s. |

¶ 79 The surface area covered by multiple habitation site components ranges from approximately 324 m2 to 57,500 m2 (Appendix 6.1, Table 6). The average site size (12,790 m2) is considerably larger than for single habitations (4,896 m2). This reflects the presence of a few very large sites in the Chacra Mesa survey area, although the median site size is still a substantial 10,000 m2. The largest multiple habitation sites are all in the Chacra Mesa survey area. Surface area of multiple habitation site components is broken down by time period in Table 6.9. Only the Chacra Mesa survey area contained sufficient numbers of sites for each period to produce meaningful average figures. There, sites occupied from 1700 to 1863 are substantially smaller than those dating to the two more recent periods.

|

Table 6.9. Multiple habitation components: mean area in m2 by time period. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kin Bineola | Kin Klizhin | South Addition | Chacra Mesa | All Areas | ||

| 1700-1863 | ||||||

| No. of Components | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 | |

| Mean Area | 9,279 | 10,559 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 6,448 | 7,150 | ||||

| 1868-1930 | ||||||

| No. of Components | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 7 | |

| Mean Area | 16,048 | 14,616 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 9,039 | 9,078 | ||||

| 1930-19803 | ||||||

| No. of Components | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Mean Area | 18,010 | 18,010 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 18,049 | 18,049 | ||||

| Other | ||||||

| No. of Components | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 8 | |

| Mean Area | 11,592 | 9,134 | ||||

| Std. Dev. | 7,998 | 8,185 | ||||

| All Sites | ||||||

| No. of Components | 1 | 1 | 2 | 27 | 31 | |

| Mean Area | 12,000 | 13,561 | 12,790 | |||

| Std. Dev. | 12,445 | 11,300 | 11,095 | |||

¶ 80 Habitation structures at multiple habitation sites include 93 hogans and three houses. Hogans are present on all 30 sites. Most are like those described for single habitation sites, circular or oval constructs of simple sandstone slab masonry (Figures 6.12 and 6.13). The masonry walls presently stand from one to nine courses high, with a maximum wall height of 1.4 m. Evidence of mortar is usually not present, although it is present in three of the best-preserved hogans, all at 29SJ 2966.

|

Figure 6.12. View of Hogan 1 at 29SJ 2606, a multiple habitation site dated to 1776-1850. |

|

Figure 6.13. View of a well-preserved hogan ring (Hogan 1) at 29SJ 2908, dated to 1910-1935. |

¶ 81 The doorways in the three hogans at 29SJ 2966 are framed with wooden posts. Most commonly, door frames are made of large upright sandstone slabs. One hogan (at 29SJ 2701) has a possible passage entryway extending out from the main structure about 80 cm. Like the hogan, the sides of the entryways are of simple sandstone masonry. Passage entryways have been recorded on hogans elsewhere in Chaco Canyon (Malcolm 1939:7) and on Big Bead Mesa (Keur 1941:29).

¶ 82 Evidence of interior hogan features was found at several sites. Eight hogans exhibit fire-reddening on interior walls where hearths were probably located. Three contain evidence of internal bins or storage cists formed of upright slabs. One hogan which was built against a cliff has a small niche in the cliff wall, which was probably used as a storage space. Several hogans were dug into the talus slope. Sometimes up to 2.4 to 2.7 m of earth was removed from the uphill side to form a level floor inside the hogan.

¶ 83 Interior diameter of stone hogans ranges from about 2 m to 7.4 m (mean=3.4 m; sd=0.97 m). The smallest hogan at a multiple habitation site measures 1.7 x 1.87 m (Appendix 6.1, Table 5). Diameters of 2.5 to 4.0 m were most common and hogans with diameters of more than 4.0 m are more common at multiple habitation sites than single habitations.

¶ 84 As was found with single habitation sites, the average floor area of hogans at multiple habitations increased significantly through time. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) rejected the null hypothesis that there was no significant difference in the mean hogan floor area between the 1700-1863, 1868-1930, and 1930-1980 time periods (F [2,48]=8.53, p<0.01). For the period 1700 to 1863, mean floor area was 7.5 m2 (s.d.=4.1). For 1868 to 1930, the mean floor area increased to 12.9 m2 (s.d.=5.8), and for 1930 to 1980 mean floor area increased again to 14.0 m2 (s.d.=6.0). Tukey’s family error rate between pairwise comparisons indicates that the mean hogan floor area for the 1700-1863 period is significantly different from the two subsequent time periods, but the latter two periods are not significantly different from each other. Klara Kelley (1982b:53) found a similar trend at sites near Black Hat, New Mexico, which she attributes to an increased length of occupation during the year at dwelling sites. The greater the proportion of the year a dwelling was occupied, the more activities were necessarily performed there and the more goods stored inside.

¶ 85 Brush, logs, or poles, the likely remains of roofs, found in association with hogans were much more commonly found at multiple habitation sites. At least partially intact cribbed-log roofs were present on hogans at 29SJ 2966 (a multiple habitation site) and 29SJ 2700 (a single habitation site), providing us with a picture of how most roofing was probably constructed (Figure 6.6). The four hogans with intact roofs have standing masonry walls between 1.10 and 1.35 m high. It is presumed, therefore, that most other stone hogans in the project area were built of masonry to that approximate height and then roofed with cribbed logs. There is evidence that after abandonment some of the stone hogans were stripped of construction materials, particularly roof beams, for use in building new hogans. Brugge (1986:29) notes that beams used at 29SJ 2700 (Brugge’s Site “N”) are said to have originally come from structures at another site north of Chaco Wash. Several of the hogans show indications of reuse for other purposes after abandonment. At least one abandoned hogan appears to have been reused for storage.

¶ 86 Only one double hogan was recorded at the 30 multiple habitation sites. This structure could not be dated to a specific period. Other hogan types include the forked-stick variety and several with no standing walls. Those with no walls consist of mere depressions with a few scattered sandstone slabs and the type of construction is unknown. The remains of three probable forked-stick hogans were recorded at one multiple habitation site, 29SJ 2606. Seven masonry hogans and a house were also present on this site. Tree-ring dates from two of the forked-stick hogans and one stone hogan produced dates from 1771 ++G to 1793 +rGB (Appendix 6.1, Table 2), suggesting construction occurred in the 1780s or 1790s and that the two types were contemporaneous. Ceramic dates from the site corroborate this time frame. The forked-stick hogans (Hogans 9, 10, and 11) are clustered at the southeastern edge of the site (Figure 6.10), each identified by the presence of a sandstone slab foundation. Two exhibited long juniper poles scattered over the foundations, one with two forked-end poles. The third forked-stick hogan appears to have been built against three large talus boulders.

¶ 87 Houses at multiple habitation sites were built very much like stone hogans and are distinguished only by their rectangular floor plans. All three are simple rectangular structures located on sites which also contain circular hogans. The house at 29SJ 2459, in the Kin Klizhin survey area, is unique (Figure 6.14). It dates to between 1920 and 1935. The main room of the house is dug into a low shale hill. The walls are lined with compound sandstone slab masonry, standing to a height of 1.9 m. The room contains two slab-lined shelves in the west wall and a window in the south wall. A short masonry-lined passageway extends east from the main room into a second room outlined by sandstone blocks. This second room contains a slab-lined box (possible fireplace) and a shelf. A more recent addition to the structure is an 11 by 12 m rectangular compound outlined by upright juniper posts, probably used as a corral.

|

Figure 6.14. View of house at 29SJ 2459, a multiple habitation site dated to 1920-1935. |

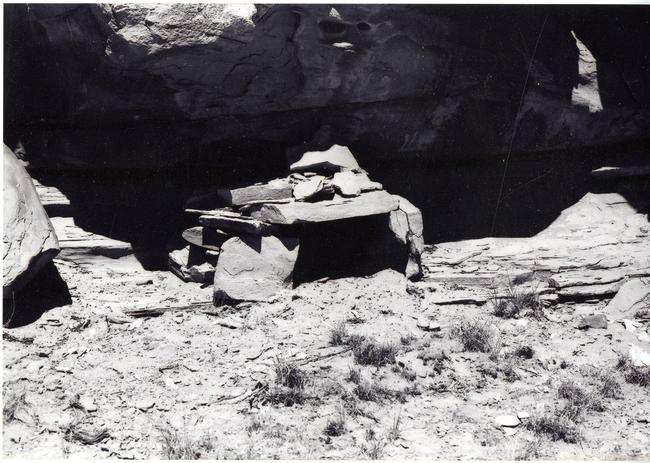

¶ 88 Storage facilities are present on 13 of the 30 multiple habitation sites (Table 6.8). They include storage rooms, cists, and bins (see Appendix 6.2 for definitions). The number of storage rooms is usually limited to one or two, although as many as five were noted. They were found in association with 1868 to 1930 and 1930 to 1980 period site components (Table 6.10). Construction of storage rooms was like that at single habitation sites. Most are stone, generally dry-laid, roughly stacked sandstone slabs closing off a space partially formed by a ledge or outcrop of talus boulders. In two of the five storage rooms at 29SJ 2966, remnants of the wooden roof remain (Figure 6.15), one with upright roof posts still in situ. Unoccupied hogans at some of the sites may also have been used to store food and equipment.

|

Figure 6.15. View of a storage room at 29SJ 2966, a multiple habitation site dated from 1940 to the early 1950s. |

|

Table 6.10. Major features present at dated multiple habitation components. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1700-1863 | 1868-1930 | 1930-1960 | |

| No. of Habitation Components | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| No. with Corrals | - | 5 (71%) | 4 (57%) |

| No. with Storage Facilities | - | 3 (43%) | 4 (57%) |

| No. with Wood Chopping Area or Wood Piles | - | 2 (28%) | 4 (57%) |

| No. with Sweat Lodges | - | - | 2 (28%) |

| No. with Temporary Shelters | 1 (11%) | 2 (28%) | 2 (28%) |

| Note: Percentages shown in this table represent the proportion of components of a given time period at which a given feature type is present. For example, in the 1930-1960 time period, four (57%) of seven multiple habitations have corrals. | |||

¶ 89 Corrals are present at 14 (47 percent) of the multiple habitation sites, lamb pens at two (Table 6.8). Both lamb pens are small masonry enclosures. Construction of corrals is highly variable. Most are built of stacked sandstone slabs and/or blocks or stacked brush. Several are of wood post and barbed wire construction. As at single habitation sites, the corrals commonly take advantage of sandstone outcrops in forming an enclosure. An excellent example of this is found at 29Mc 515 (Figure 6.9), where five corrals are formed in natural alcoves. Corral size ranges from small circular structures less than 3 m in diameter to the large “V”-shaped enclosure at 29Mc 515, which measures 57 by 30 m. No corrals were recorded with Pre-Bosque Redondo components. Seventy-one percent of the 1868 to 1930 multiple habitations and 57 percent of the 1930 to 1980 multiple habitation components contained corrals (Table 6.10).

¶ 90 At both single and multiple habitation sites, the mean area enclosed by corrals for the Post-Bosque Redondo Period (1868 to 1930) was compared with mean corral area for the Modern Period (1930 to 1980), revealing no significant change in size through time (t[14]=0.382, p=0.708). From 1868 to 1930 the average total area enclosed by corrals (per site) was 446 m2 (sd=517). For 1930 to 1980 it was 359 m2 (sd=271). Although not statistically significant, this 20% reduction in corral size probably reflects the effects of the stock reduction program which was implemented in 1934. Why corral size did not decline more is difficult to determine. The smaller than expected size decline could be a product both of the relatively small sample of corrals, and the difficulty of precisely dating them.

¶ 91 Temporary shelters are found at seven multiple habitation sites, most (6 out of 7) in the Chacra Mesa survey area (Table 6.8). These structures are generally indicated by sparse remains: outlines of sandstone rubble or small wall segments, sometimes with associated brush. A very small rock shelter (2.3 by 1.7 m) is located at one site. Shades or windbreaks are suggested by the presence of standing juniper limbs at two sites (Figure 6.16). The presence of a tent is indicated on at least one site, 29SJ 2703, where a tent peg with an associated wood cutting area and trash scatter were found. A flattened area at 29SJ 2986 with an ash pile and wood cutting area to the southeast may also have been a tent platform. Temporary shelters are found at multiple habitation components from all three time periods (Table 6.10).

|

Figure 6.16. View of shade or windbreak remains at 29Mc 491, a post-1930 multiple habitation site. |

¶ 92 The remains of three sweat lodges were found at three sites, all on Chacra Mesa (Table 6.8). Two of these sites are dated to the 1930 to 1980 time period (Table 6.10). More habitation sites probably had sweat lodges than the data indicate, but many were located so far from habitations that they were recorded separately. None of the three sweat lodges recorded remain standing and only two contain scattered tree limbs which were probably part of the superstructure. The identification of these structures is based primarily on the presence of burned sandstone scatters or piles and rock heating hearths. As at single habitations, the sweat lodges are all located away from habitations and general activity areas, on the peripheries of sites.

¶ 93 Wall segments of unknown function and other unidentified structures were recorded at six sites (Table 6.8). These are generally thought to be the remains of poorly preserved storage rooms, lamb pens, or temporary shelters such as windbreaks. A sandstone slab foundation, said to be the base of a feeding trough used by Hispanic herders, was found at one Navajo multiple habitation site reused as a sheep camp (York: field notes).

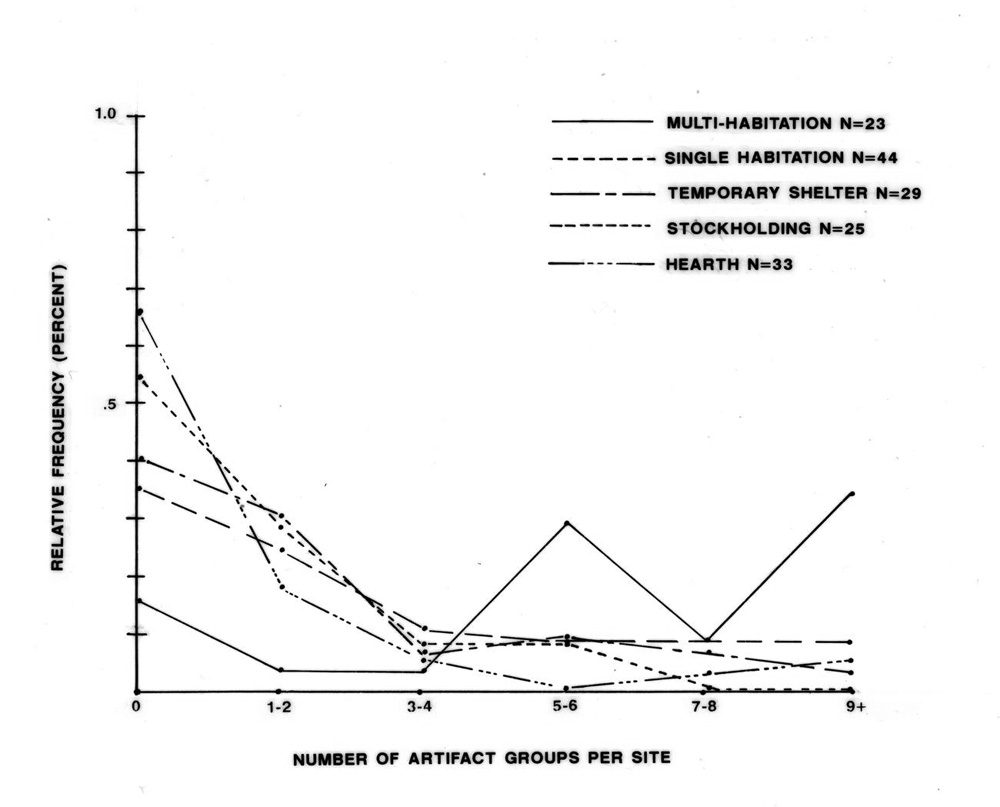

¶ 94 Other features commonly found on multiple habitation sites are hearths, ovens, ashpiles and/or trash scatters, fire-altered rock, rock piles and other rock features, water control features, rock art, wood chopping areas, trails, road segments, sherd and lithic scatters, and general Euro-American refuse (Table 6.8). The abundance and nature of these features do not differ markedly from those at single habitation sites. Less frequently found on multiple habitations are old fence lines, burials, wood piles or scatters, coal mines, clay quarries, and evidence of children’s play such as doll houses and a stone concretion cache.